The Geography of Attention

A buried city in Israel. An Ice Age settlement in the UK. A tomb in Egypt. These are the stories of the ancient world most likely to grace American headlines. But an equally significant discovery in China, or a temple site in West Africa? More often than not, those findings don’t make the cut.

A new study led by Bridget Alex and colleagues, published in Science Advances1, dives into the systemic bias in how American media covers archaeology. It reveals an uneven landscape, where the past is not only interpreted but filtered—curated through cultural, religious, and racial lenses.

“Coverage of archaeology in China/Taiwan lagged significantly behind, even when controlling for journal prestige, press release availability, and publication volume.”

What gets covered shapes what’s remembered. And what’s omitted leaves a silence that, in archaeology, often gets filled with myth and misuse.

Pasts That Resonate—and Those That Don’t

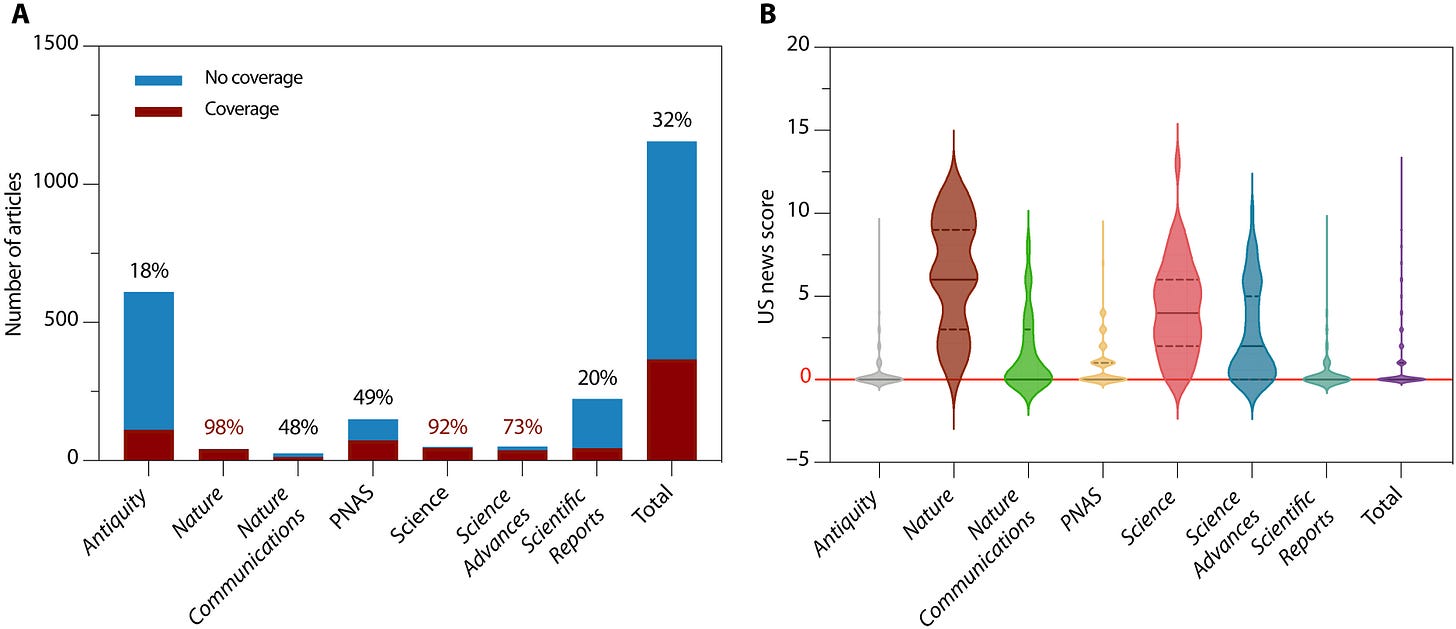

The team analyzed more than 1,100 peer-reviewed archaeology papers published between 2015 and 2020 across top journals like Nature, Science, and PNAS. Of these, only about 32% were covered by major U.S. media outlets. The pattern of coverage skewed heavily toward studies focused on the United Kingdom, Israel/Palestine, Egypt, and the United States itself.

Regions like China, Central Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa were significantly underrepresented. Even when papers from these regions appeared in elite journals, they struggled to gain traction in the press.

Paleolithic archaeology—studies about early human origins—was more likely to be covered, especially when it framed discoveries as “shared” or “universal.” But as the research narrowed in on specific cultures or histories, the likelihood of coverage depended on how well those narratives meshed with imagined American identities.

“The media’s framing of archaeology favors pasts linked to European, Christian, or ‘civilizational’ themes—pasts that feel proximate to dominant U.S. cultural narratives.”

Invisible Hands in the Newsroom

Press releases mattered. Articles featured on the EurekAlert! distribution system were four times more likely to be picked up. Yet here too, bias reared its head: stories about archaeology in the U.S., U.K., and Israel were more likely to receive promotional support than those about China or Latin America.

The demographic profile of science journalists also plays a role. U.S. newsrooms remain disproportionately white, and story selection tends to reflect editorial assumptions about what resonates with “general” (read: white, middle-class) audiences.

“Who gets to decide what stories are told? And which pasts count as relevant?”

Bias with Consequences

Selective coverage in archaeology isn’t just a matter of editorial taste. It has tangible impacts. It reinforces public perceptions that civilizations from certain regions are more advanced or historically meaningful than others. It can feed nationalistic myths or be co-opted by racist ideologies claiming exclusive ownership of human achievement.

When Indigenous or non-Western pasts are ignored, the communities tied to those histories are further marginalized. Funding, museum exhibits, educational curricula, and public memory all follow the trail blazed by media attention.

“When archaeological stories about Africa, Asia, or Indigenous America are omitted, it sends a message about who belongs in history—and who doesn’t.”

Re-calibrating the Lens

The study urges scholars, journalists, and institutions to reflect on how knowledge about the past gets filtered before reaching the public. Recommendations include:

Broadening the geographic range of press releases.

Proactively covering studies from underrepresented regions.

Diversifying newsroom leadership and journalistic voices.

Teaching media literacy in archaeology education.

At its core, this is a call to reimagine how societies engage with the ancient world—not as a mirror of existing power structures, but as a complex, global mosaic.

“To democratize the past, we must first democratize who gets to tell its stories.”

Additional Related Research

Stojanowski, C. M., & Duncan, W. N. (2017). Bioarchaeology as a Tool for Constructing Identity in the Past and Present. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol., 162(S63), 110–128. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.23147

Fagan, G. G. (2006). Diagnosing Pseudoarchaeology. Archaeology, 59(2), 18–23. https://www.archaeology.org/issues/194-1603/letter-from/4121-letter-from-england-diagnosing-pseudoarchaeology

Kaiser, W. (2011). One Past, Many Presents. Antiquity, 85(328), 5–11. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003598X0006755X

Moshenska, G. (2010). Ethics and Values in Archaeology. Public Archaeology, 9(2), 73–80. https://doi.org/10.1179/175355210X12766170223404

Stanczyk, A., & Wacquant, L. (2020). The Racial Politics of Heritage. Theory and Society, 49, 397–425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-020-09380-2

Alex, B., Ji, J., & Flad, R. (2025). Regional disparities in US media coverage of archaeology research. Science Advances, 11(26), eadt5435. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adt5435