Few fossils in Europe have sparked as much debate as the skull from Petralona Cave in northern Greece. Discovered in 1960, the nearly complete cranium seemed to belong to a hominin that was neither Homo sapiens nor Neanderthal. For decades, its age was anyone’s guess, with estimates ranging from 170,000 to 700,000 years old. A new study1 narrows that window considerably—and deepens the mystery of who this individual was.

Dating a Skull Without Dating the Bone

Bones alone often refuse to give up their secrets, particularly when it comes to age. In the damp environment of Petralona Cave, the original bone material lacked enough organic content for radiocarbon dating. Previous attempts using indirect methods produced wildly inconsistent results.

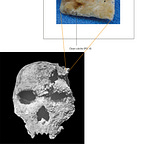

This time, researchers turned to uranium-series dating. Rather than the bone itself, they analyzed the calcite crust that had grown over the cranium while it sat in the cave. When water carrying dissolved uranium dripped onto the skull and dried, it left behind tiny layers of mineral deposits. Those deposits act like a clock: as uranium decays into thorium at a known rate, scientists can calculate how long the crust has been forming.

The innermost layer of calcite on the cranium provided a minimum age of 286,000 years, with a margin of ± 9,000 years. That doesn’t reveal when the individual died, only when the skull began accumulating calcite. It could have been resting there even earlier.

“The calcite tells us the latest possible time the skull was exposed to dripping water,” explains study co-author Christophe Falguères. “It’s a minimum bound. The fossil itself may be older.”

An Ancient Neighbor, Not Quite Us

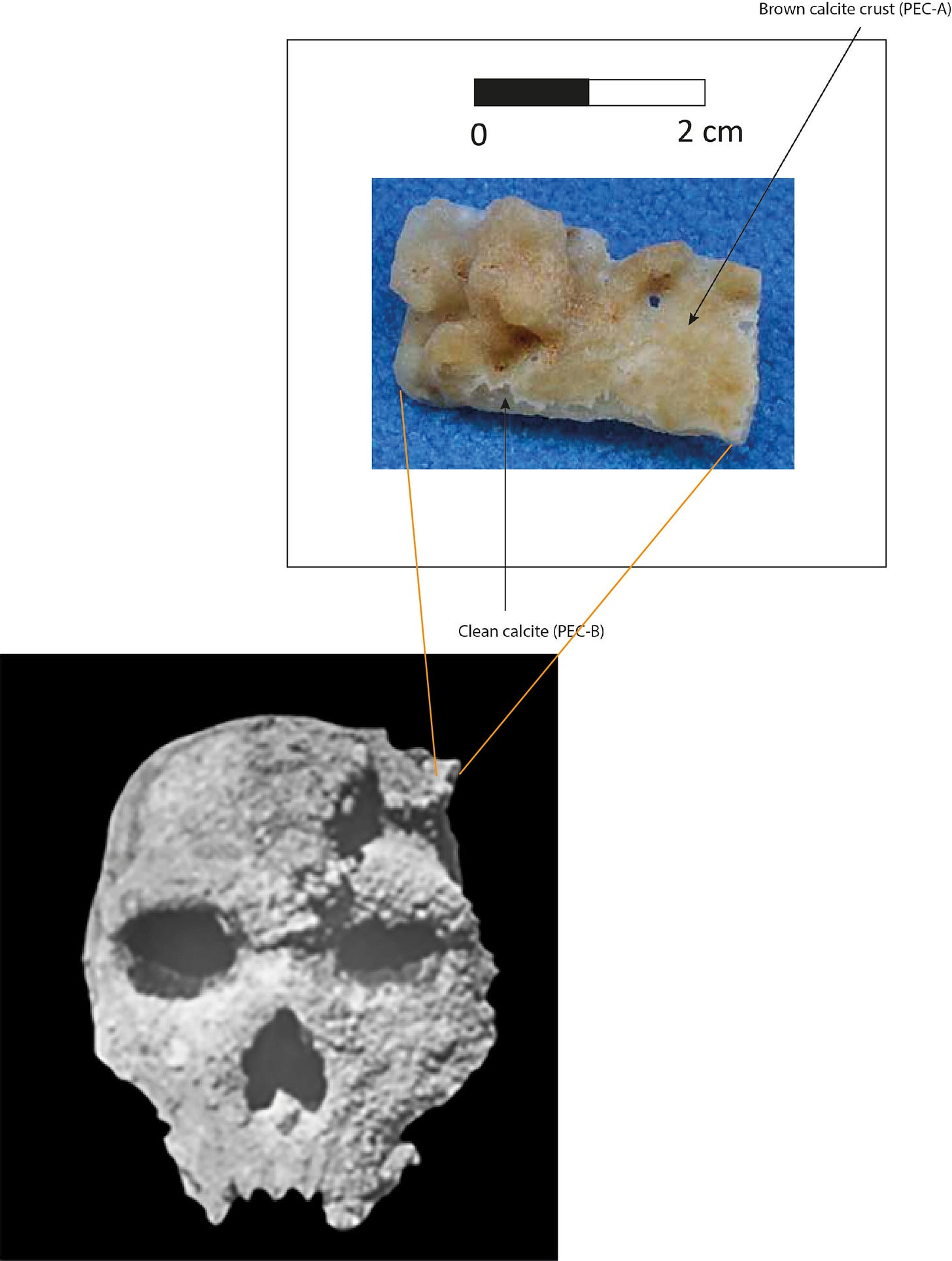

Stratigraphic clues from elsewhere in the cave add more context. Speleothem layers in the chamber known as the Mausoleum suggest parts of the cave were forming over half a million years ago. That makes it plausible that the Petralona hominin lived during the later Middle Pleistocene—a period when Europe was home to a mosaic of human populations.

The morphology of the Petralona skull remains distinctive. It does not fit neatly with Neanderthals, nor with early Homo sapiens. Instead, researchers see affinities with more archaic hominins, possibly part of a lineage that coexisted alongside early Neanderthals in Europe.

“This fossil shows that human evolution in Europe was not a simple linear progression toward Neanderthals,” notes the team. “It suggests a complex population structure, with groups diverging and perhaps occasionally interacting.”

Why It Matters

Every new date for an old fossil ripples across our evolutionary timeline. If the Petralona skull truly falls between 286,000 and over 400,000 years old, it reinforces the picture of Europe as a patchwork of hominin populations long before modern humans entered the scene. It also underscores how traits we associate with Neanderthals or our own species may have evolved in parallel among different groups.

Further Reading & Related Research

Hublin, J.-J., & Roebroeks, W. (2009). The prehistory of Neanderthals and modern humans in Eurasia. Science, 326(5949), 1081-1088. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1181716

Mounier, A., & Lahr, M. M. (2019). Deciphering African late Middle Pleistocene hominin diversity and the origin of our species. Nature Communications, 10, 3406. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-11213-w

Stringer, C. (2012). The status of Homo heidelbergensis (Schoetensack 1908). Evolutionary Anthropology, 21(3), 101-107. https://doi.org/10.1002/evan.21311

Falguères, C., Shao, Q., Perrenoud, C., Stringer, C., Tombret, O., Garbé, L., & Darlas, A. (2025). New U-series dates on the Petralona cranium, a key fossil in European human evolution. Journal of Human Evolution, 206(103732), 103732. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2025.103732