About 9,500 years ago, people living near Mount Hora in what is now northern Malawi built a large open-air pyre1 and cremated the body of an adult woman. This single event, preserved in ash and bone fragments beneath a rock shelter, is the earliest confirmed case of intentional human cremation in Africa and the oldest known cremation pyre to contain adult remains anywhere in the world. Far from being a marginal curiosity, the pyre forces archaeologists to rethink assumptions about social organization, ritual labor, and remembrance among early African hunter-gatherers.

Fire, Bone, and a Mountain Called Hora

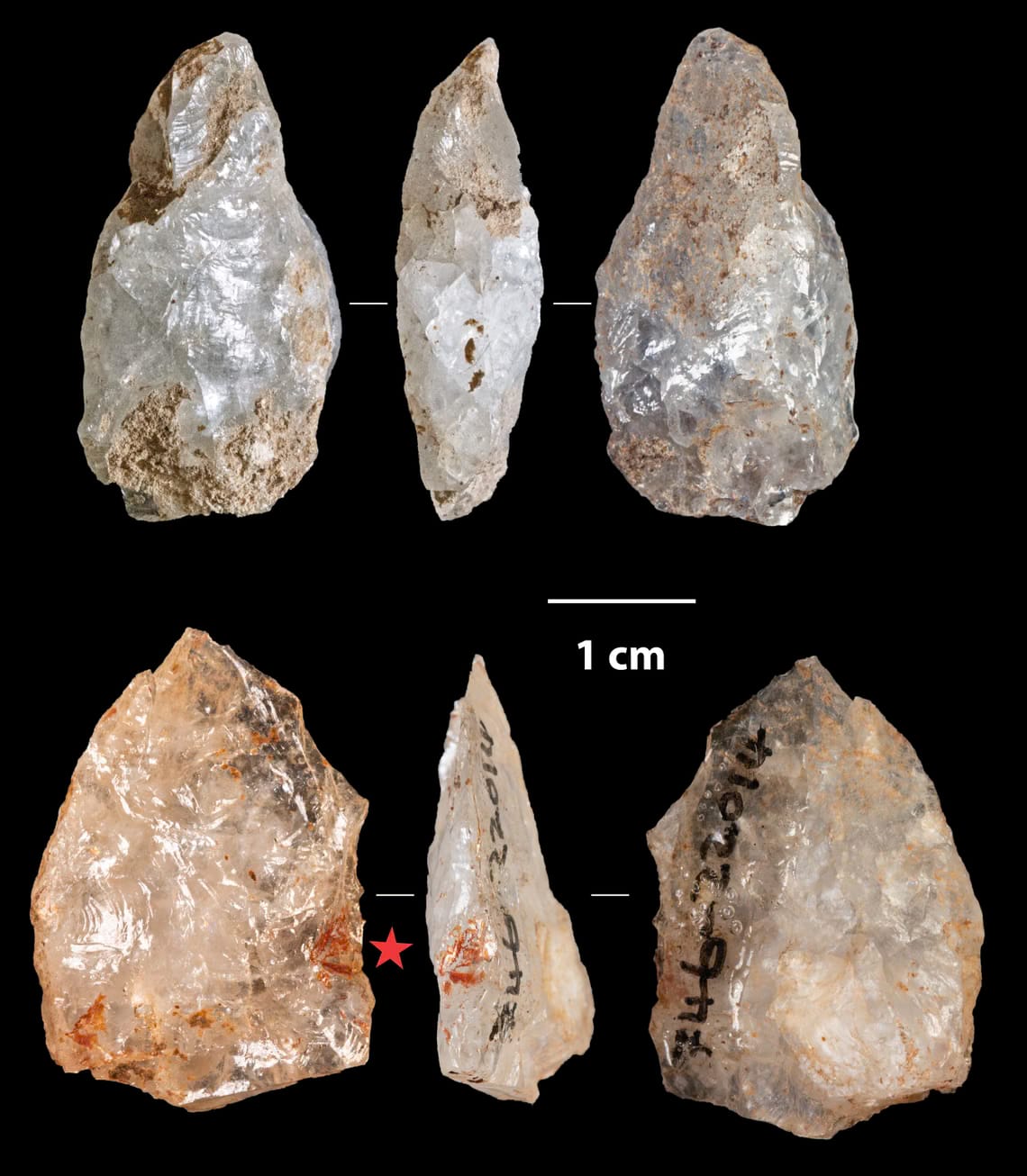

At the base of Mount Hora, a granite inselberg rising sharply from the surrounding plain, archaeologists uncovered something unexpected. Beneath a shallow rock overhang lay a dense ash feature roughly the size of a queen bed. Embedded within it were 170 fragments of human bone, heavily burned and fractured.

The site is known as Hora 1. It had long been recognized as a burial place for ancient hunter-gatherers, but until recently all known burials there involved intact bodies placed in the ground. This one was different.

Radiocarbon dating places the cremation at roughly 9,500 years ago. The remains belonged to an adult woman, likely under five feet tall. Her arms and legs were well represented. Her skull and teeth were entirely absent.

This absence mattered. Teeth and cranial fragments usually survive cremation well. Their disappearance suggests deliberate removal before the fire was lit.

As the authors write in Science Advances:

“The pattern of skeletal representation and thermal alteration indicates that the body was burned shortly after death and that some elements, particularly the cranium, were removed prior to cremation.”

This was not an accident. It was a carefully staged act.