For much of the twentieth century, the story of prehistoric hunting read like a tidy ladder. First came the thrusting spear, pressed into flesh at arm’s length. Then the spear-thrower extended the hunter’s reach. Finally, at the top rung, the bow and arrow appeared, elegant and efficient, a late flourish of technological sophistication.

It was a comforting sequence. It was also probably wrong.

A new study led by Keiko Kitagawa and colleagues, published in iScience1 in 2025, argues that early Upper Paleolithic Homo sapiens in Eurasia may already have been using bows and arrows some 40,000 years ago. Not everywhere. Not all the time. But alongside other weapons, as part of a flexible hunting toolkit rather than a single evolutionary endpoint.

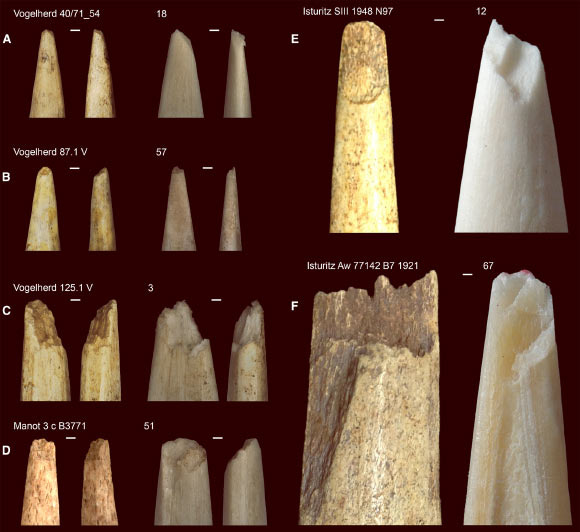

The claim does not rest on preserved bows or arrow shafts. Those almost never survive. Instead, it comes from something subtler: how antler and bone projectile points break when they hit flesh and bone at speed.