In the foothills of Uzbekistan’s Tien Shan mountains lies a rock shelter that may hold a surprising chapter in human technological history. Excavations at Obi-Rakhmat have revealed stone fragments that researchers argue were likely parts of projectiles, possibly even arrowheads, dating to nearly 80,000 years ago. If confirmed, this would place the origins of bow-and-arrow technology tens of thousands of years earlier than many archaeologists once believed.

The study, published in PLOS ONE1, combines microscopic wear analysis and experimental archaeology to assess whether small stone points excavated from the site could have been used as hunting weapons.

“The presence of fractured micropoints in these layers suggests they were mounted on shafts and used as projectiles,” the authors write. “Their size and morphology make them most consistent with arrow-like tips rather than heavy spearheads.”

The site and its layers

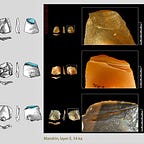

Obi-Rakhmat sits in the Paltau valley at the southwestern edge of the Talassky Alatau range. Archaeological deposits at the site span 21 sedimentary levels across ten meters, covering a timeframe between about 90,000 and 40,000 years ago. Layers 20 and 21, the oldest excavated so far, yielded a trove of lithics: nearly 200 small triangular flakes and 194 point specimens, some shaped using Levallois reduction techniques.

Of these, 20 pieces were set aside as possible weapon tips. Researchers began with macroscopic observations of impact-related breakage, then moved to stereoscopic and reflective optical microscopy to examine surface wear.

Experiments with ancient tools

To test their hypotheses, the team replicated the tools using local silicified limestone and mounted them on wooden shafts. Using a 36-pound laminated bow, they shot these experimental armatures at a small ungulate carcass. The results were telling: several of the stone points fractured on impact in ways that matched the archaeological specimens.

The study identified three classes of possible armatures: large retouched points (likely used as spear tips), bladelets that may have served as inserts, and the most intriguing—micropoints, small triangular flakes averaging just 18 millimeters wide and often weighing little more than a gram.

These micropoints showed microscopic impact traces consistent with high-velocity penetration, making them unlikely candidates for thrusting spears. Instead, their lightweight design fits better with arrows.

What this means for human evolution

If the interpretation is correct, Obi-Rakhmat would push the use of arrow-like projectiles back to 80,000 years ago, deep within the Middle Paleolithic. That predates the commonly accepted timeline for bow-and-arrow technology, usually associated with Homo sapiens populations in Africa around 60–70,000 years ago.

This raises the question of who the makers were. Fossils from Obi-Rakhmat include remains with both Homo sapiens and Neanderthal-like traits, fueling debate over whether the occupants were an admixed population. The projectile evidence now adds another layer to the mystery, suggesting that complex weapon systems may have been present in Central Asia earlier than expected.

“Evidence for small, lightweight armatures at Obi-Rakhmat demonstrates the possibility of diverse hunting strategies during the Middle Paleolithic,” the authors note, “challenging assumptions that complex projectile technology only emerged during the Upper Paleolithic.”

For archaeologists and anthropologists, the implications extend beyond weaponry. Projectile technology has long been linked to shifts in social organization, cooperative hunting, and even cognitive planning. If arrows were part of the toolkit this early, the behavioral capacities of hominins in Central Asia may need to be re-evaluated.

Open questions

The evidence is still limited, and the researchers themselves stress the need for larger samples to confirm the findings. It remains unclear whether these tools were widely used for hunting or represent early experiments with new technology. Further excavations may help establish whether such lightweight projectiles persisted in later layers, bridging the Middle to Upper Paleolithic transition.

Related Research

Villa, P., & Soriano, S. (2010). Hunting weapons of the Middle Stone Age and the Middle Paleolithic: spear points from Sibudu, South Africa, and comparable assemblages. Journal of Archaeological Science, 37(3), 309–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2009.09.043

Shea, J. J. (2006). The origins of lithic projectile point technology: evidence from Africa, the Levant, and Europe. Journal of Archaeological Science, 33(6), 823–846. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2005.10.015

Sisk, M. L., & Shea, J. J. (2009). Experimental use and quantitative performance analysis of triangular flakes (Levallois points) as projectile weapon tips. Journal of Archaeological Science, 36(9), 2039–2047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2009.05.023

Lombard, M., & Phillipson, L. (2010). Indications of bow and stone-tipped arrow use 64,000 years ago in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Antiquity, 84(325), 635–648. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003598X00100134

Plisson, H., Kharevich, A. V., Kharevich, V. M., Chistiakov, P. V., Zotkina, L. V., Baumann, M., Pubert, E., Kolobova, K. A., Maksudov, F. A., & Krivoshapkin, A. I. (2025). Arrow heads at Obi-Rakhmat (Uzbekistan) 80 ka ago? PloS One, 20(8), e0328390. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0328390