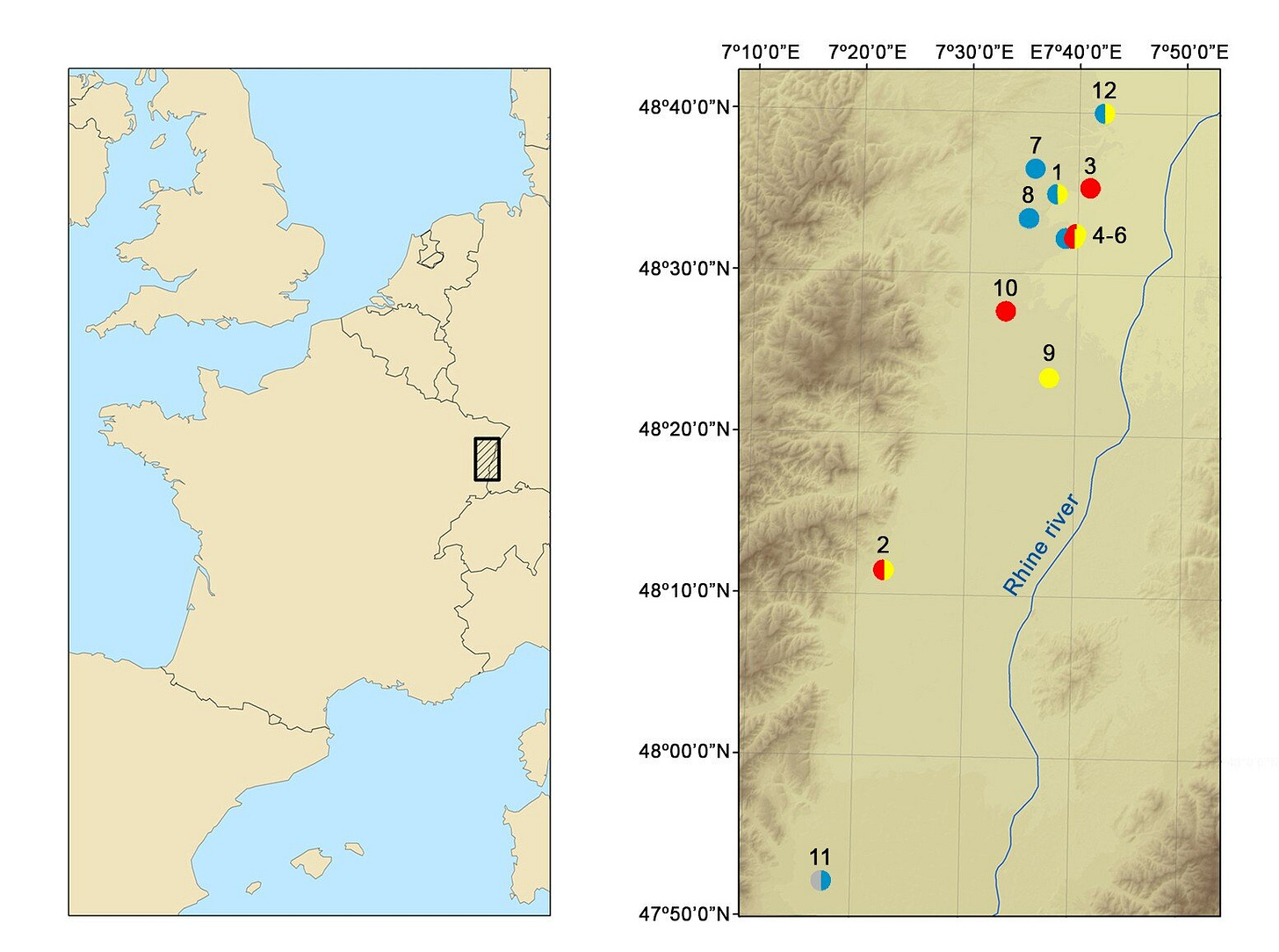

In the lush green valley of the Upper Rhine, some 6,000 years ago, a human drama of conquest and cultural clash unfolded. This wasn't a world of gleaming palaces or written histories, but one of small villages and stone tools. Yet, buried beneath the soil of what is now northeastern France, at sites called Achenheim and Bergheim, archaeologists found evidence of a chilling conflict. Within two circular pits, human remains were found haphazardly piled—some with unhealed trauma and excessive, brutal violence, others missing a left upper limb altogether. These pits were a puzzle, a silent testament to a violent event that defied easy explanation.

Were the victims social outcasts, ritually sacrificed by their own people? Or were they fallen warriors, brought back by their community for burial? To answer these questions, a team of researchers, led by Teresa Fernández-Crespo, turned to a powerful tool of modern archaeology: multi-isotope analysis. Their work, published in Science Advances, provides a detailed look into the lives—and deaths—of the individuals in these pits, revealing a story of a war of conquest and the ceremonial brutality that followed.

Reading a Life in Bone and Tooth

The study focused on 82 human remains from the two sites, dividing them into two groups: "victims" who showed evidence of violence and "non-victims" who were buried with what appeared to be normal funerary rites. The researchers used isotope analysis, which measures the ratios of stable isotopes of elements like carbon (δ13C), nitrogen (δ15N), and sulfur (δ34S) in bone and tooth collagen and enamel. These ratios reflect a person's diet and the geology of their environment, providing a chemical fingerprint of where they lived and what they ate throughout their life.

By analyzing bone collagen, scientists can reconstruct a person's diet and mobility over their final years. Tooth enamel and dentine, on the other hand, form at different stages of childhood and adolescence, creating a long-term record of early life, including infant and child-rearing practices and mobility patterns. The researchers hypothesized that if the victims were from the same community, their isotopic signatures should be similar to the non-victims. If they were outsiders, their isotopic data would be different.

Outsiders and Their Brutal Demise

The results were stark. ]The victims, whether complete skeletons or severed limbs, were isotopically distinct from the non-victims.

Dietary Differences: The victims showed significant differences in their diet or the environment where their food originated compared to the local non-victims. At the Bergheim site, victims had markedly higher nitrogen isotope values, which could suggest a greater intake of animal-based protein or higher physiological stress.

Geographic Origin: The sulfur isotope values revealed the most significant differences. Non-victims had a tight range of values, consistent with a local population exploiting a restricted landscape. In contrast, the victims' sulfur values showed much greater variation. Interestingly, the severed left upper limbs had lower sulfur values compared to the complete skeletons in the same pits, suggesting they came from a different region, possibly northern Alsace.

A Mobile Childhood: The analysis of tooth enamel provided a look into the victims' early lives. It showed that victims had more frequent and pronounced isotopic shifts, particularly in strontium (87Sr/86Sr) ratios, indicating they were more mobile during childhood than the non-victims.

These findings strongly suggest that the victims were not local community members but outsiders, likely from invading groups. This supports the hypothesis that the violence was not a form of intragroup punishment but was instead a war-related practice.

A Public Spectacle of Violence

The pits themselves tell a graphic story. One hypothesis is that the severed limbs were trophies taken from enemies who fell in battle and were brought back to the village for display. The complete skeletons, on the other hand, may have been captives brought to the village alive and killed as part of a victory celebration.

“The most likely scenario is that the severed upper limbs were trophies taken from the bodies of enemies fallen in battle or raids immediately after death and brought to the village. Heads and hands seem to be the most common human trophies documented in the archaeological record, although written and ethnographic sources often refer to other body parts, including soft tissues which would not generally preserve, such as scalps, ears, or genitals.”

The public nature of the pits, located in central community spaces, suggests these events were an orchestrated “political theater” to reinforce community solidarity and dehumanize the enemy.

“Victims may have addressed spiritual goals (e.g., provided food and slaves for ancestors or gods), legitimized political authority through the display of merciless brutality, and paid tribute to glory. The dehumanized image created of the enemy—commonly portrayed as depraved and evil, thus meriting cruelty and retaliation—during protracted conflict would enable perpetrators to kill and maim and the rest of the community to support such actions through moral disengagement. The fear of what happens if a demonized enemy is not overcome—or at least contained—would become a justification for perpetuating or even escalating violence.”

This study provides one of the earliest and most detailed accounts of martial victory celebrations in prehistoric Europe. It shows that violence in the Neolithic was not always a simple massacre or execution. It could be ritualized, symbolic, and deeply political, used to legitimize power and justify the brutal treatment of the "other."

Additional Related Research

The analysis of stable isotopes is a powerful method for reconstructing past human lives. Here are a few examples of how it has been used to shed light on violence, mobility, and identity in prehistoric and ancient societies.

Evidence of Cannibalism: A study on human remains from a mass grave in Germany revealed evidence of perimortem blunt force cranial trauma. Isotope analysis helped characterize the victims as nonlocals, suggesting they were outsiders subjected to capital punishment, a conclusion that was supported by the systemic targeting of the head.

Meyer, C. et al. Early Neolithic executions indicated by clustered cranial trauma in the mass grave of Halberstadt. Nature Communications 9, 2472 (2018). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-04217-1, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-04217-1

Ritualized Violence and Human Sacrifice: A separate study of the El Mirador Cave in Spain, dating to the Late Neolithic, used multi-isotope analysis to show that victims of a violent episode were from the local community. The presence of cut marks, scrape marks, and human tooth marks on the bones suggested a rare case of systematic consumption of the victims, likely over a few days.

Fernández-Crespo, T. et al. Large-scale violence in Late Neolithic Western Europe based on expanded skeletal evidence from San Juan ante Portam Latinam. Scientific Reports 13, 17103 (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-023-44163-x, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-44163-x

Tracing Mobility of Hominin Groups: Isotope analysis has been used to trace the movement of individuals across landscapes. A study on a Neanderthal from Spain, for example, used strontium isotope ratios to determine that the individual likely migrated from a different region to join the group in the cave where their remains were found.

Richards, M. P. et al. Isotopic evidence for the diet of an Early Upper Palaeolithic Neanderthal from Mezmaiskaya Cave, Russia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 101, 17926–17930 (2004). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0408127101, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0408127101