When maize first emerged from its wild ancestor, teosinte, in the valleys of central Mexico some 9,000 years ago, the transformation above ground was dramatic. Kernels once locked in hard, inedible shells swelled into soft, starchy grains. But below the surface, changes were equally crucial, if less visible.

A recent study in New Phytologist1 suggests that the roots of maize—those unseen structures binding plant to soil—were shaped by both human agricultural practices and natural shifts in climate and soil over thousands of years (Lopez-Valdivia et al. 2025).

“We reconstructed the root phenotypes of corn and teosinte, as well as the environments of the Tehuacán Valley… using a combination of ancient DNA, paleobotany and functional-structural modeling to reconstruct how root traits evolved over time,” said Jonathan Lynch, plant nutrition researcher and senior author of the study.

Roots in Deep Time

The researchers built their analysis around one of the most archaeologically rich regions of Mesoamerica: the Tehuacán Valley. Known for some of the earliest evidence of maize domestication, the valley’s soils and pollen records preserve traces of environmental change over the last 18,000 years.

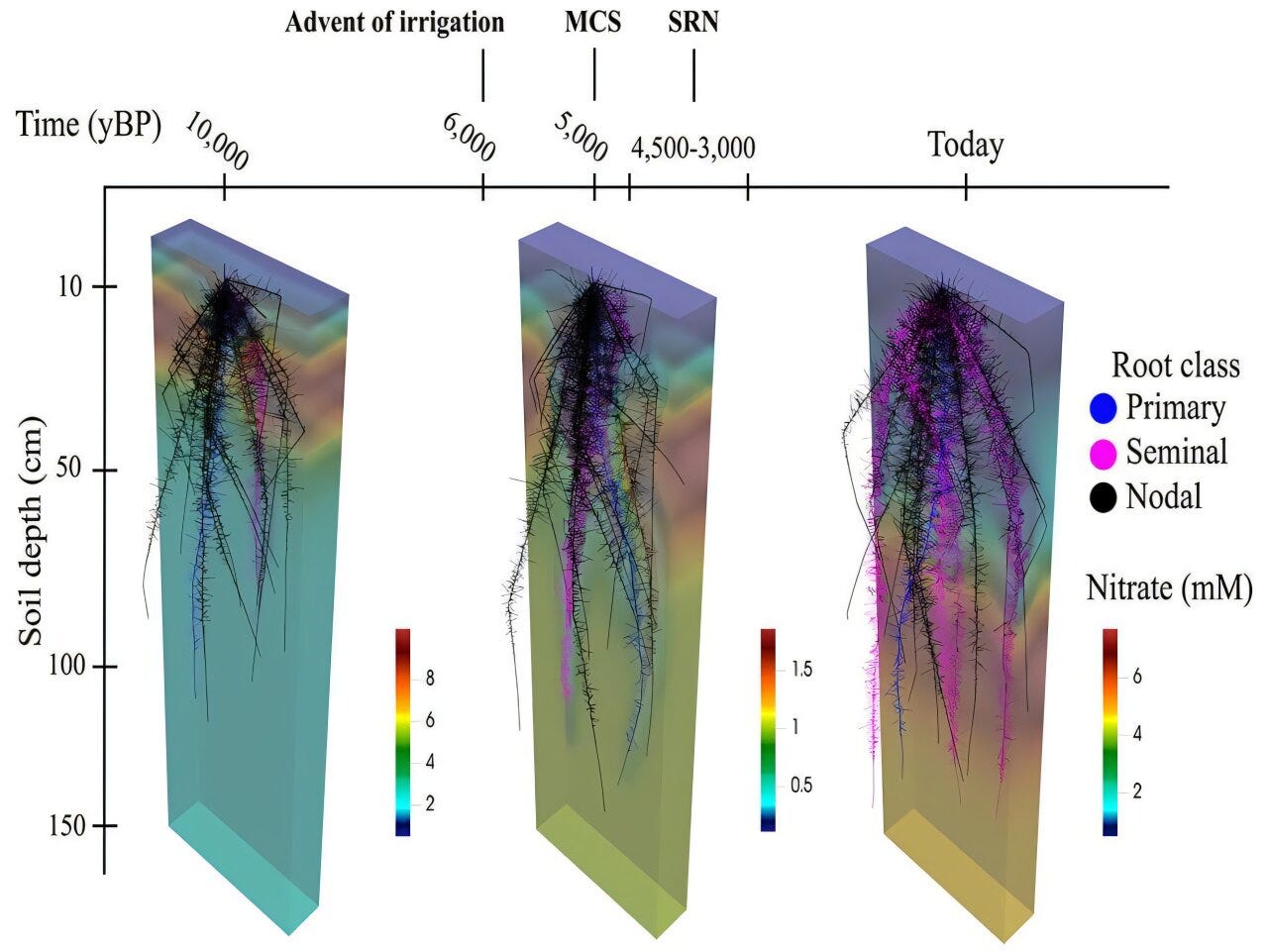

By combining ancient DNA with computer simulations (the OpenSimRoot model), the team traced how maize roots shifted in step with climate pressures and changing cultivation techniques.

Three key evolutionary changes stood out:

Fewer nodal roots – the shallow roots sprouting from the stem base declined, giving way to deeper foraging.

The rise of multiseriate cortical sclerenchyma – a dense tissue that allows roots to penetrate harder, drier soils.

More seminal roots – early-developing roots that anchor seedlings and extract nutrients in their most vulnerable stage.

These shifts suggest that maize adapted not only to human cultivation but also to fluctuating rainfall, soil degradation, and rising atmospheric CO₂.

Farming, Climate, and Root Evolution

The study identified three distinct phases of root evolution:

12,000–8,000 years ago: Rising CO₂ levels encouraged deeper rooting, helping early maize draw water and nutrients from below.

Around 6,000 years ago: Irrigation spread through the valley, pushing nitrogen deeper into the soil. Maize with tissues designed for deep penetration thrived.

By 3,500 years ago: Agricultural intensification and soil depletion made early root systems critical. More seminal roots appeared, ensuring seedlings could establish quickly in stressed soils.

“The research suggests that root phenotypes that enhance plant performance under nitrogen stress were important for corn adaptation to changing agricultural practices,” explained lead author Ivan Lopez-Valdivia.

Archaeology Meets Plant Science

For archaeologists, the study adds a subterranean layer to the story of domestication. While charred cobs and grinding stones document maize’s role above ground, roots rarely leave direct traces. Yet, by reconstructing their evolution, the study ties together environmental shifts, human subsistence, and the biology of a crop that now feeds much of the planet.

The findings also highlight how the plant-human relationship was not one-sided. Farmers selected plants for larger kernels, but soils and climate nudged the species in directions that would prove essential for long-term survival.

Looking Forward

As maize remains one of the most widely planted crops today, the ancient dance between roots, soils, and human cultivation may offer lessons for the future. Rising CO₂ and shifting rainfall patterns once again threaten crop stability. Understanding how ancient maize adapted to change could help guide breeding programs today.

“That’s not only interesting historically… it also gives some guidance as to what we can do with corn roots in the future to make them better adapted to developing conditions,” Lynch noted.

Related Research

Piperno, D. R., Ranere, A. J., Holst, I., & Hansell, P. (2000). Starch grains reveal early root crop horticulture in the Panamanian tropical forest. Nature, 407(6806), 894–897. https://doi.org/10.1038/35038055

Kistler, L., Maezumi, S. Y., de Souza, J. G., Przelomska, N. A., Costa, F. M., Smith, O., & Allaby, R. G. (2018). Multiproxy evidence highlights a complex evolutionary legacy of maize in South America. Science, 362(6420), 1309–1313. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aav0207

Wang, H., Studer, A. J., Zhao, Q., Meeley, R., & Doebley, J. F. (2015). Evidence that the origin of naked kernels during maize domestication was caused by a single amino acid substitution in teosinte glume architecture1. Genetics, 200(3), 965–974. https://doi.org/10.1534/genetics.115.176651

Lopez-Valdivia, I., Vallebueno-Estrada, M., Rangarajan, H., Swarts, K., Benz, B. F., Blake, M., Sidhu, J. S., Perez-Limon, S., Sawers, R. J. H., Schneider, H., & Lynch, J. P. (2025). In silico analysis of the evolution of root phenotypes during maize domestication in Neolithic soils of Tehuacán. The New Phytologist. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.70245