For decades, archaeologists have debated the story of how farming reached Europe. Was it a sweeping wave of new people replacing old ones? Or a cultural contagion—ideas spreading faster than genes? A new study published in Science Advances1 suggests a more intricate reality: farmers and foragers didn’t just meet, they lingered, lived side by side, and eventually intertwined.

The Long Transition

About 9,000 years ago, farmers from western Anatolia began moving into the Balkan Peninsula, carrying with them domesticated plants, animals, and a radically different way of life. They followed rivers like the Danube, pushing gradually into the heart of Europe. But they didn’t find empty land. Hunter-gatherers were already there, deeply rooted in their landscapes and traditions.

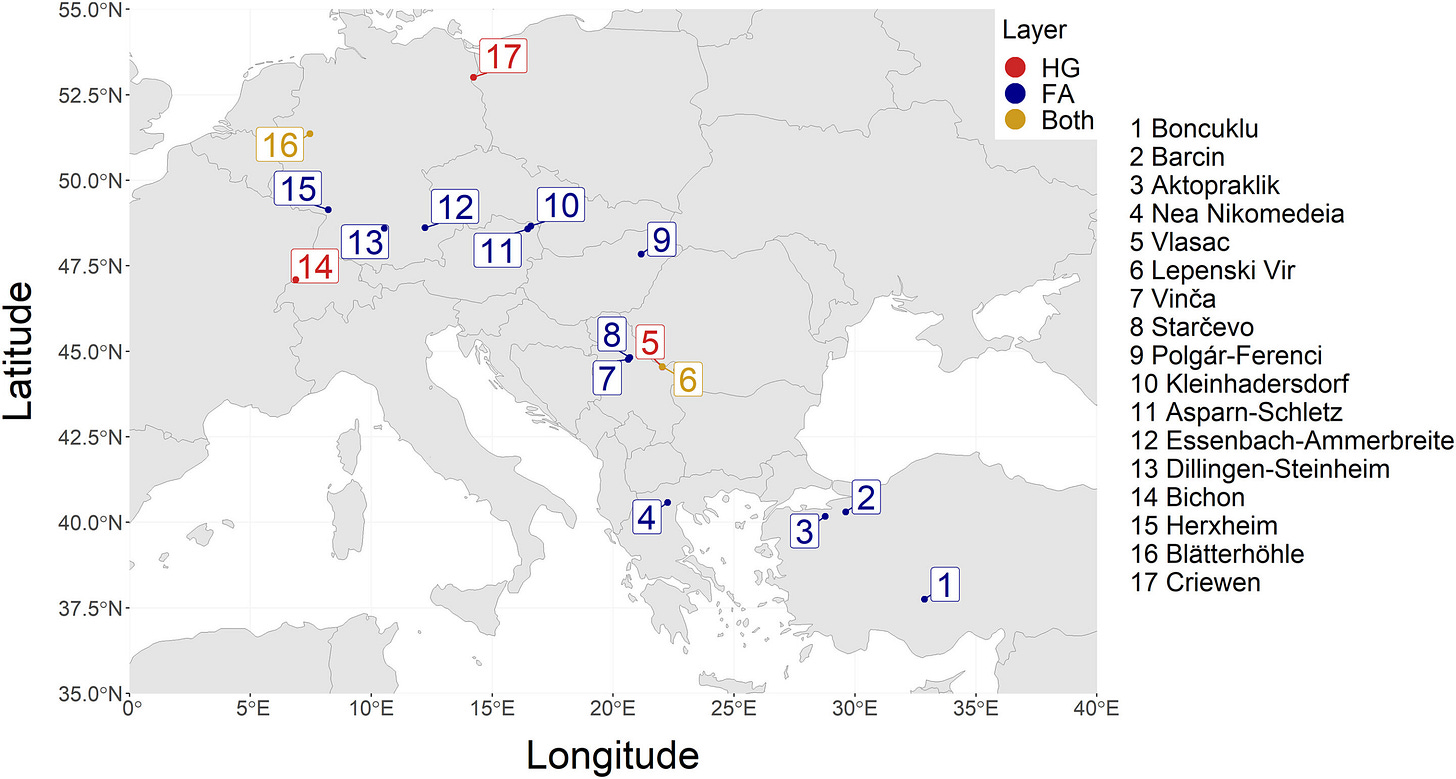

For a long time, these two worlds coexisted. They shared space, exchanged goods—and eventually genes. That’s the picture painted by researchers who combined computer modeling with ancient DNA data from 67 individuals buried across Central and Southeastern Europe.

“The Neolithic transition was not characterized by violent confrontation or complete replacement, but by prolonged coexistence with increasing levels of interbreeding,” said Alexandros Tsoupas, lead author of the study.

Simulating an Ancient Encounter

The team, based at the University of Geneva, built demographic models to simulate the expansion of farming communities along the Danube route. They input population sizes, reproduction rates, migration behaviors, and potential contact scenarios between the two groups. Then they tested these models against real genetic data extracted from prehistoric skeletons.

The result? A pattern emerged: when farmers first arrived in new regions, interbreeding with local hunter-gatherers was rare. But as years—or perhaps centuries—passed, that genetic exchange grew more common.

“These simulations generated thousands of scenarios,” explained Mathias Currat, a population geneticist on the team. “By comparing them with actual DNA, we were able to estimate the most likely dynamics of interaction.”

Five Times the Numbers

One of the clearest differences between the two groups was scale. Farming communities were larger—roughly five times the size of local forager bands. Their demographic weight, combined with occasional long-distance moves, allowed them to spread rapidly across the continent. But spread did not mean erase.

Instead, what unfolded was a mosaic. In some regions, hunter-gatherer genes persisted for centuries, blending into the genetic fabric of early farmers. In others, isolation delayed contact, preserving cultural differences for generations.

A Quiet Transformation

This nuanced picture matters because it challenges older narratives of sudden replacement or violent conquest. Instead, Europe’s first farmers and its last foragers lived through a period of overlap, negotiation, and fusion. Their story suggests that cultural transitions—especially ones as profound as the adoption of agriculture—are rarely neat or instantaneous.

Today, echoes of this encounter linger in our genomes. Most Europeans carry traces of both lineages: the mobile foragers of the Pleistocene and the farmers who followed.

Why It Matters

This research not only reshapes how we think about the past, it also highlights the tools now available to archaeologists: computational models and paleogenomics can reconstruct population histories in unprecedented detail. They show that human history, like human identity, is layered and dynamic.

Related Research

Here are some closely related studies for deeper reading:

Lazaridis, I. et al. (2014). Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans. Nature, 513, 409–413. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13673

Mathieson, I. et al. (2015). Genome-wide patterns of selection in 230 ancient Eurasians. Nature, 528, 499–503. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16152

Haak, W. et al. (2015). Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe. Nature, 522, 207–211. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14317

Lipson, M. et al. (2017). Parallel palaeogenomic transects reveal complex genetic history of early European farmers. Nature, 551, 368–372. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature24476

Tsoupas, A., Reyna-Blanco, C. S., Quilodrán, C. S., Blöcher, J., Brami, M., Wegmann, D., Burger, J., & Currat, M. (2025). Local increases in admixture with hunter-gatherers followed the initial expansion of Neolithic farmers across continental Europe. Science Advances, 11(34). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adq9976