The story of human history is often told through tools, temples, and tombs. But sometimes, it’s the smallest things—a stroke of eyeliner or a warped skull—that tell us the most about how people lived, suffered, and expressed their identity. Two recent studies from southwestern and northwestern Iran peel back time to reveal how appearance, injury, and identity shaped life and death in antiquity.

In a fifth millennium BCE burial at Chega Sofla, a young woman lay with her skull visibly altered by the bands that once bound her head. That same skull was also violently fractured. Thousands of years later and hundreds of kilometers north, in an elite Iron Age tomb near the Assyrian frontier, a cosmetic jar preserved the shimmering black powders of an ancient eye makeup—a blend of graphite and manganese, untouched by lead.

Together, these discoveries from the Zohreh and Kani Koter regions offer two faces of the human past: one marked by trauma and transformation, the other by self-presentation and aesthetic complexity.

Violence and Modification in the Copper Age

At Chega Sofla, in the lower Zohreh Plain near the Persian Gulf, archaeologists uncovered the remains of a young woman who lived—and died—more than 6,000 years ago. Her skull bore two distinct signatures: an intentional elongation from early-life cranial banding, and a fatal blow delivered just before her death.

The study, published by Mahdi Alirezazadeh and Hamed Vahdati Nasab in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology1, used CT imaging to reveal a triangular perimortem fracture stretching from her frontal to parietal bones. There was no sign of healing. The force of the injury, they argue, likely came from a wide-edged tool—perhaps an axe or a club. The blow was brutal, but not penetrating. It was enough to kill.

What makes this case remarkable is not just the violence, but its intersection with cultural practice. The skull had been reshaped over years through cranial deformation, a practice known from cultures across the ancient world. Whether for social identity, beauty, or group belonging, cranial shaping involves wrapping an infant’s head to encourage elongation. But the very bones altered by tradition may have made her more vulnerable to the fracture that ended her life.

The researchers caution against overinterpretation: the motive for the blow remains unknown. Was it interpersonal violence? An accident? A ritual act? Still, the preservation of both trauma and tradition in a single skull offers a rare glimpse into how bodies were shaped—both culturally and mortally—in the ancient Near East.

Glamour on the Assyrian Frontier

While the Chega Sofla skull tells a story of fracture, another Iranian burial site speaks to flourishes—of status, style, and perhaps even luxury.

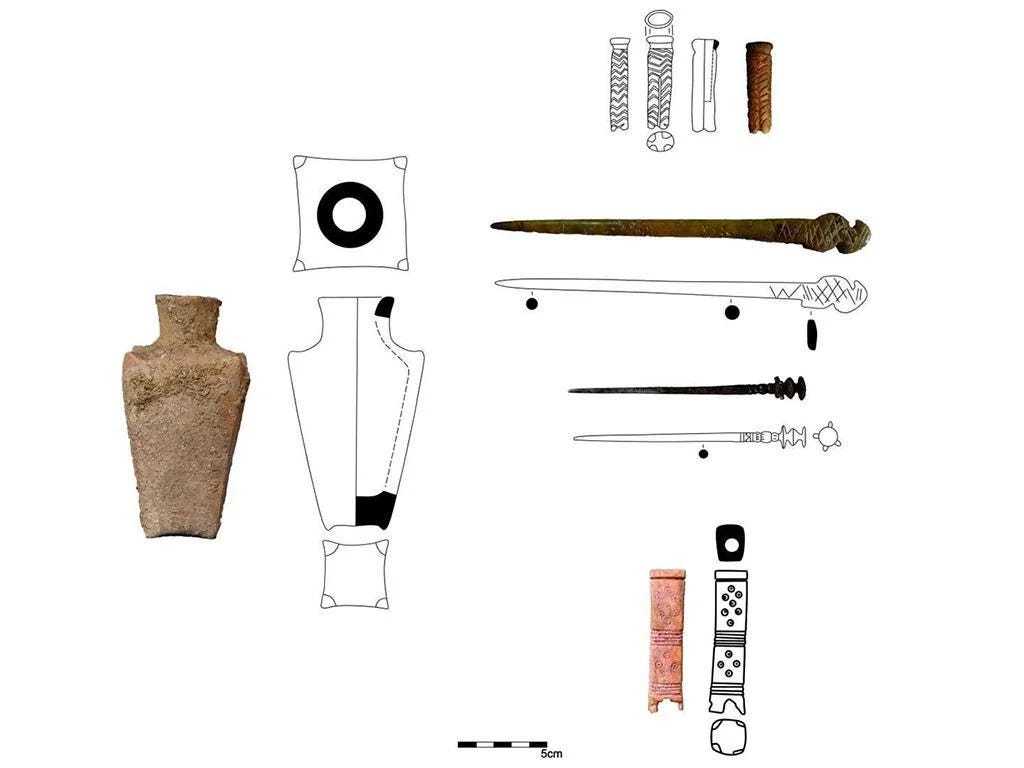

In the highlands of Iran’s Kurdistan Province, near the Iron Age cemetery of Kani Koter, archaeologists uncovered a burial chamber filled with elite items: weapons, jewelry, horse gear—and a ceramic vessel holding a fine black powder. The analysis of this powder, published in Archaeometry2 by Silvia Amicone and colleagues, revealed something never before documented in ancient cosmetics: a kohl recipe based on natural graphite and manganese oxides.

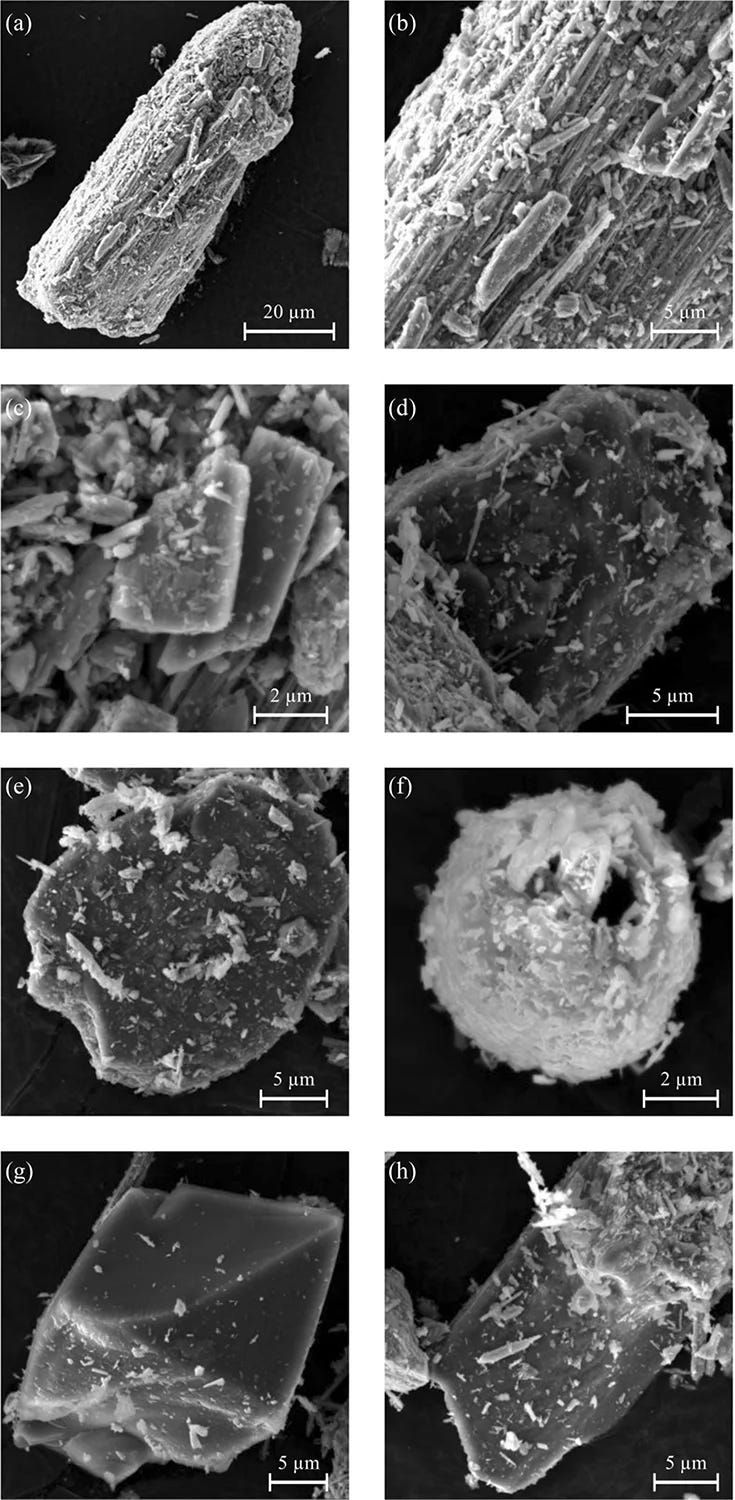

Kohl, the eye makeup used widely across Egypt and the ancient Middle East, is typically associated with lead-based ingredients. But the Kani Koter sample stands apart. Using X-ray diffraction, Raman spectroscopy, and scanning electron microscopy, the team identified pyrolusite (a manganese mineral) and natural graphite as the key blackening agents. The shimmering quality of graphite and the deep pigment of manganese combined to form a unique regional blend.

Notably absent from the mixture were organic binders such as oils or resins, which are common in Egyptian recipes. Whether this was due to preservation bias or an intentional omission is unclear. Still, the purity of the Kani Koter kohl—metallic, reflective, possibly medicinal—underscores the innovation and adaptability of Iron Age artisans.

The burial context matters too. The cosmetics were found alongside a silver tiara, bronze mirror, and ivory applicators. This was not everyday makeup. This was elite material culture, possibly used by men and women alike. Assyrian art frequently depicts rulers and warriors with rimmed eyes, hinting that cosmetic practices may have transcended gender and extended into ritual, health, and identity.

The Human Palette of Deep Time

In both cases—from the death of a modified skull to the shimmer of ancient eyeliner—what emerges is a more intimate portrait of ancient Iranian life. These discoveries invite us to rethink how people embodied power, pain, and beauty.

They also push the boundaries of archaeological science. The Chega Sofla study used radiological forensics to reconstruct trauma from bone. The Kani Koter study employed a suite of physicochemical tools to decode pigment recipes once swept around ancient eyes.

Together, these stories remind us that the archaeological record is not just about architecture and agriculture. It is about the body—modified, adorned, and sometimes broken. And through that body, we see the choices, struggles, and aesthetics of those who came before.

Alirezazadeh, M., & Vahdati Nasab, H. (2025). A young woman from the fifth millennium BCE in Chega Sofla Cemetery with a modified and hinge fractured cranium, southwestern Iran. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 35(3). https://doi.org/10.1002/oa.3415

Amicone, S., et al. (2025). Eye makeup in Northwestern Iran at the time of the Assyrian Empire: A new kohl recipe based on manganese and graphite from Kani Koter (Iron Age III). Archaeometry. https://doi.org/10.1111/arcm.13097