The Deep Past of Mummification

Long before pharaohs wrapped their dead in linen or the Chinchorro people of coastal Chile painted their desiccated ancestors, small bands of hunter-gatherers in tropical Asia were carefully tending to their dead. They lived in humid monsoon climates where natural desiccation was impossible. Yet between 12,000 and 4,000 years ago they developed a method of preservation that was as much ritual as practical: smoke-drying their dead.

The findings, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences1 show that the oldest known deliberate mummification in the world occurred in southern China and Southeast Asia, millennia before the celebrated cases of the Nile Valley or the Atacama coast.

“These burials show that the preservation of the dead was not only a technical feat but part of a shared set of beliefs spanning thousands of years and thousands of kilometers.”

The Evidence: From Caves and Shell Middens

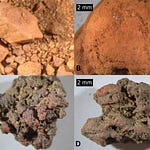

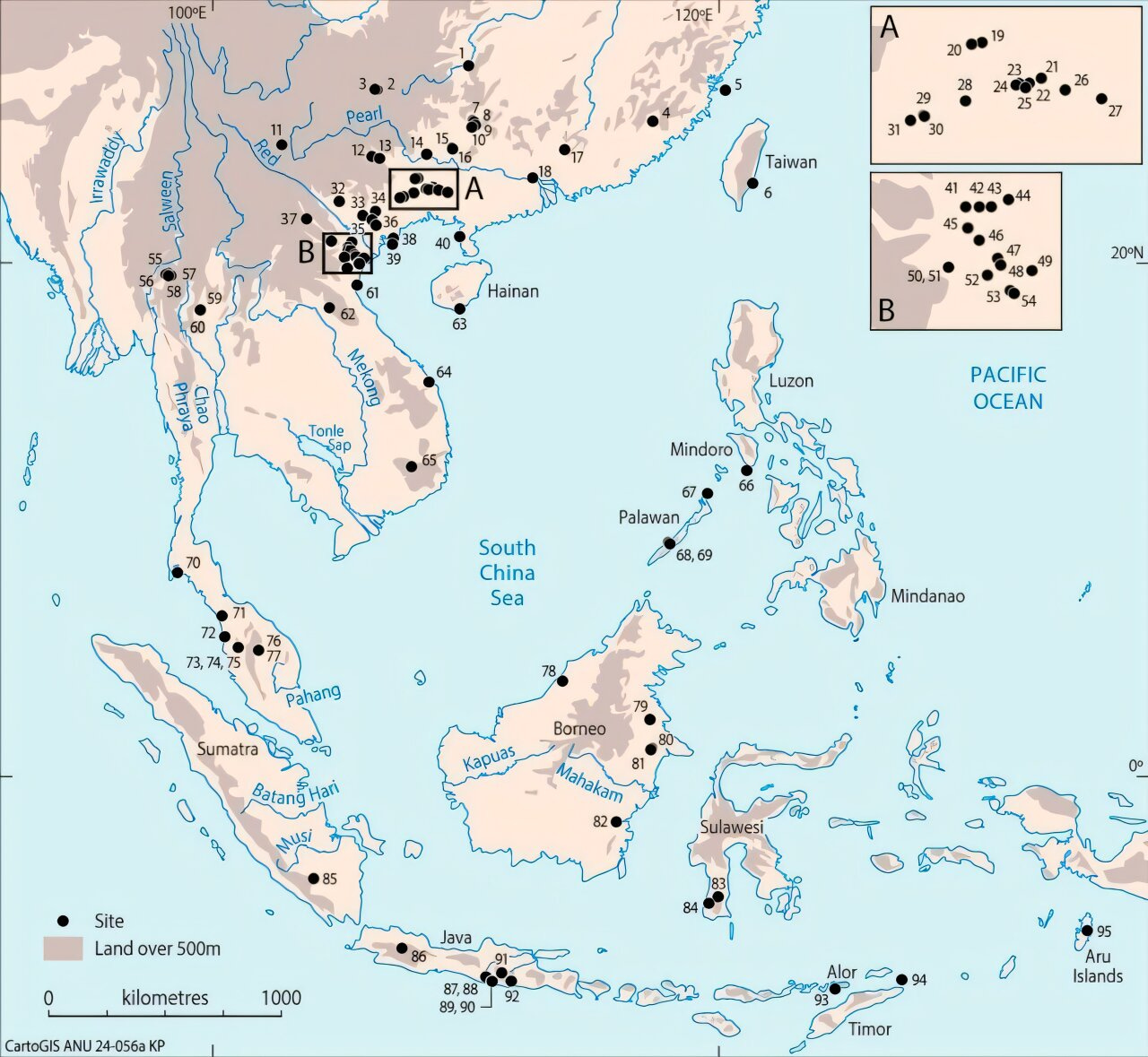

Archaeologists examined more than 50 pre-Neolithic burials from 11 sites across southern China, Vietnam, and Indonesia, including Zengpiyan Cave and Huiyaotian in Guangxi, and Con Co Ngua in northern Vietnam. The dead were buried in strikingly crouched or squatting positions. Some were tightly bound, with limbs pressed against the torso. Many showed traces of blackened bone or cut marks around major joints.

Radiocarbon dates push some of these burials back to 12,000 years ago. Laboratory tests—including X-ray diffraction (XRD) and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)—revealed subtle changes in bone chemistry consistent with exposure to low-temperature fires and long periods of smoking rather than high-heat cremation.

What Smoke-Drying Looked Like

The burn patterns suggest bodies were not burned directly but placed over or near smoldering fires. Lower limbs, elbows, and frontal areas of the skull showed the most thermal alteration, implying careful positioning.

“Rather than reducing the body to ash, smoke-drying preserved the skin and joints long enough for burial, producing skeletons so tightly flexed that no empty space remained between the limbs and torso.”

Ethnographic parallels help make sense of the archaeological record. The Dani and Anga peoples of Papua New Guinea still practiced smoke-drying of ancestors well into the 20th century, seating them above smoldering fires for months at a time. These practices produced bodies in the same tightly bound postures documented in the ancient burials.

Rethinking “Dismemberment”

Cut marks and dislocated bones once interpreted as mutilation may instead represent steps in the mummification process. In several Guangxi burials, for instance, skulls were placed in unusual positions or limbs bundled like firewood. These arrangements are consistent with post-mummification movement, delayed burial, or ritual rearrangement rather than violence.

A First Layer of Humanity

The study also reinforces the idea of an early population layer across Southeast Asia closely related to the ancestors of Indigenous Australians and Papuans. Craniofacial and genetic evidence ties the smoke-mummified individuals to this “first layer,” which arrived in the region long before Neolithic farmers swept in from the north.

“This deep biological and cultural continuity suggests smoke-drying was not an isolated custom but part of a much older tradition linking ancient Southeast Asia, New Guinea, and Australia.”

A Cultural Technology for the Tropics

Why go to such lengths? In tropical settings, bodies decompose rapidly. Smoking offered a technological solution, but the consistency of the practice across space and time implies it also carried symbolic meaning. Among the Anga, the mummified body still houses the spirit of the deceased; among Aboriginal groups in South Australia, preservation connects the dead to immortality. Such beliefs provide a glimpse of the spiritual landscape of early Homo sapiens in Southeast Asia.

Beyond Southeast Asia

Flexed burials with possible signs of smoke-drying appear in Jomon Japan, Gadokto Island off Korea, and even in parts of Australia, hinting at a broader tradition of mortuary practice that may extend back to the first dispersals of modern humans through southern Asia.

Why It Matters

This discovery reframes the timeline of one of humanity’s oldest rituals. It shows that complex mortuary behavior did not arise solely with farming societies but was deeply rooted in the hunter-gatherer past. It also underscores how ancient technologies—fire, binding, smoke—were enlisted not just for food or shelter but for shaping memory, identity, and relationships with the dead.

Related Research

Arriaza, B. T. (1995). Beyond Death: The Chinchorro Mummies of Ancient Chile. Smithsonian Institution Press.

Aufderheide, A. C., et al. (1993). The Chinchorro mummies of northern Chile. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 91(2), 189–201. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.1330910206

Reid, J., et al. (2021). Mortuary variability and body treatment in the Jomon Period. Quaternary International, 574, 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2020.07.006

Lloyd-Smith, L., et al. (2013). New insights from the Niah Cave burials, Sarawak. Antiquity, 87(337), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003598X0004999X

Matsumura, H., & Oxenham, M. (2014). Demographic transitions and migration in prehistoric Southeast Asia. Proceedings of the Japan Academy Series B, 90(6), 239–249. https://doi.org/10.2183/pjab.90.239

Hung, H., Deng, Z., Liu, Y., Ran, Z., Zhang, Y., Li, Z., Kaifu, Y., Huang, Q., Nguyen, K. T. K., Le, H. D., Xie, G., Nguyen, A. T., Yamagata, M., Simanjuntak, T., Noerwidi, S., Fauzi, M. R., Tolla, M., Wetipo, A., He, G., … Matsumura, H. (2025). Earliest evidence of smoke-dried mummification: More than 10,000 years ago in southern China and Southeast Asia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 122(38), e2515103122. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2515103122