A Planet Recalibrated

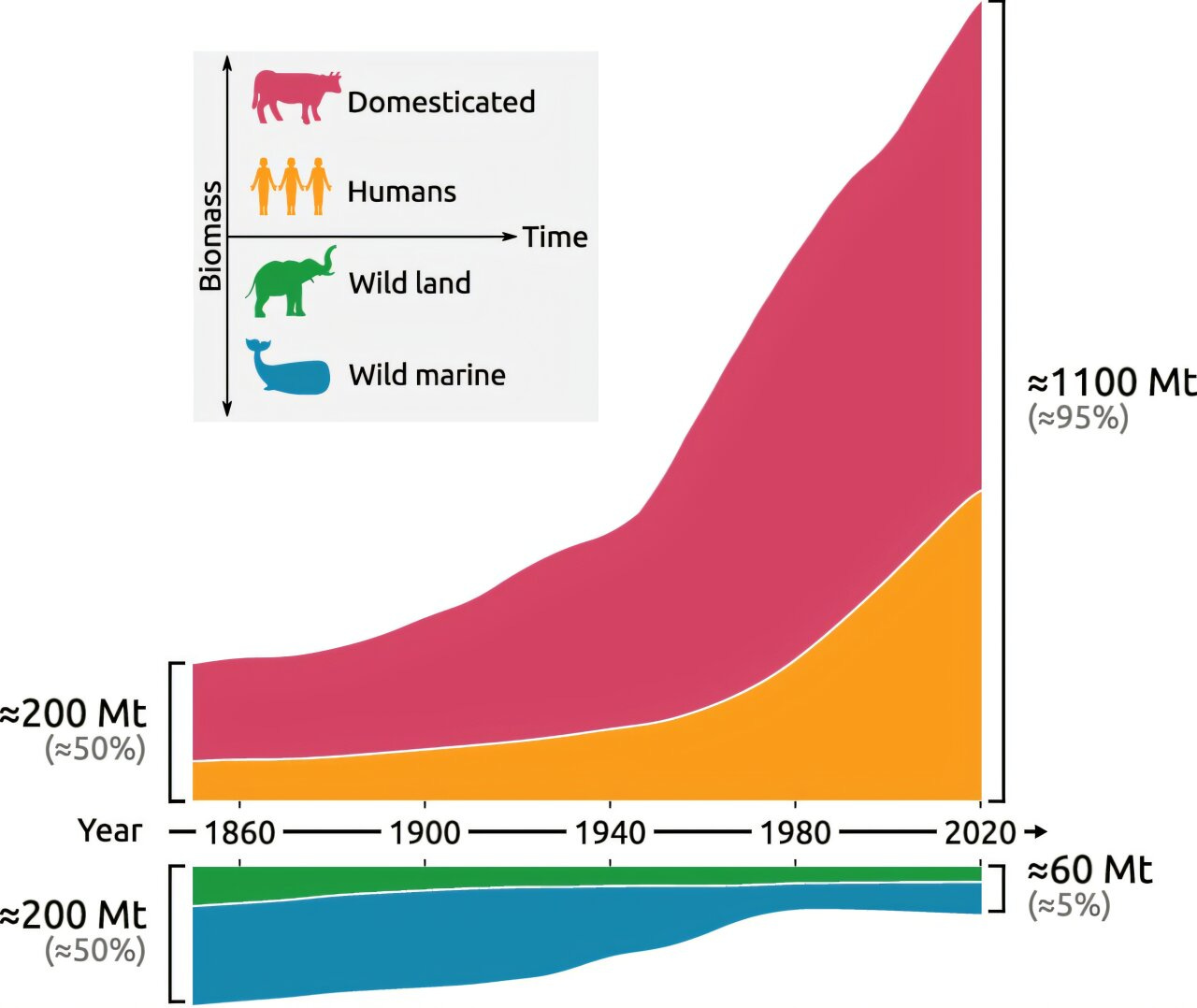

In 1850, the Earth’s mammals shared something close to equilibrium. The combined weight of all wild species—from whales to elephants—was roughly equal to that of humans and their livestock. Fast-forward 170 years, and the scale has tipped beyond recognition.

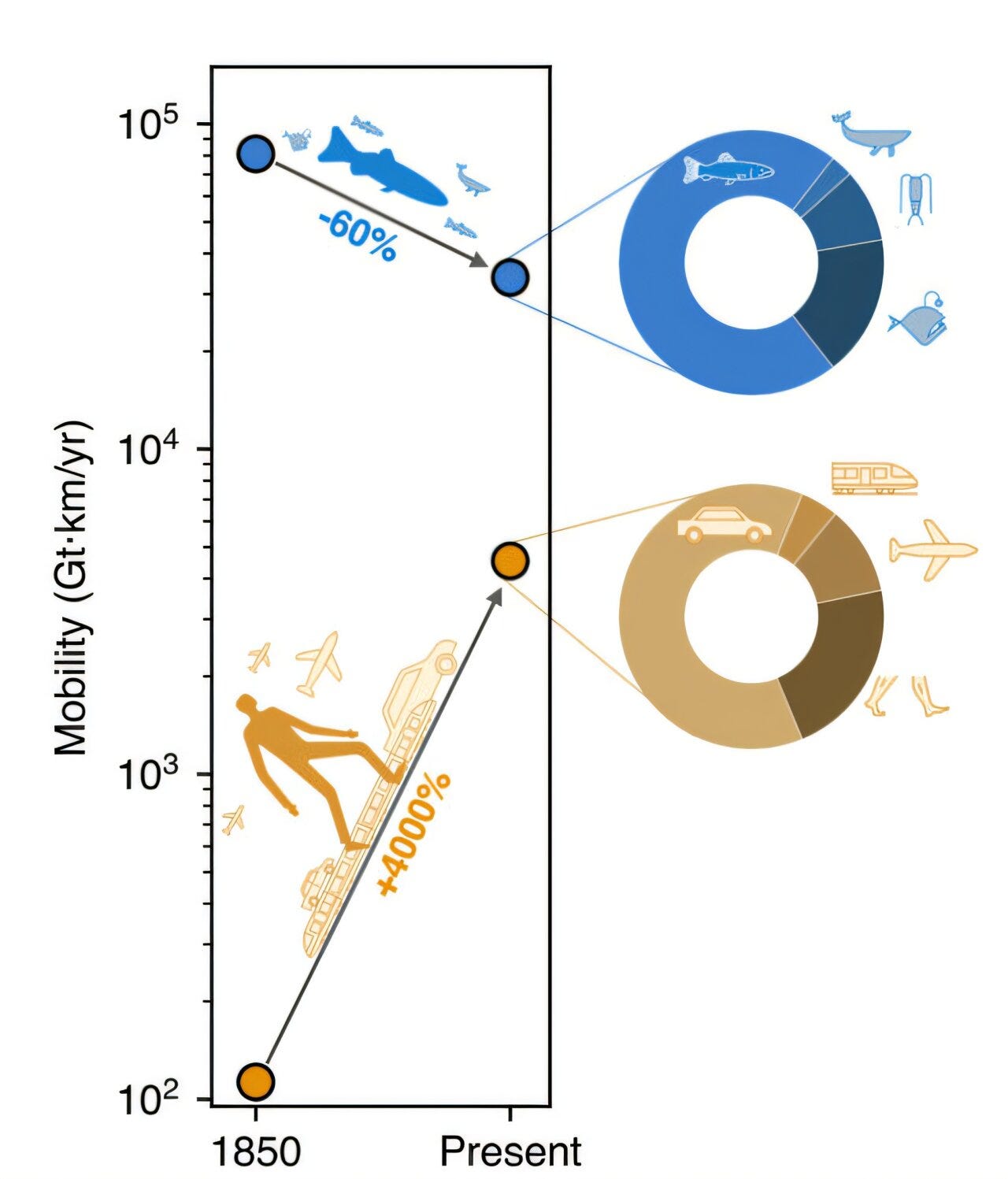

According to two1 studies2 from the Weizmann Institute of Science, the biomass of wild mammals has dropped by more than 70%, while that of humans and domesticated animals has surged sevenfold. Together, we now account for nearly 1.1 billion tons of mammalian mass, an order of magnitude greater than everything still living in the wild.

“The data show that we’ve not only changed ecosystems but fundamentally altered the planet’s physical composition,” explains Dr. Yuval Rosenberg, an ecologist at the Weizmann Institute. “The balance that defined the Holocene no longer exists.”

This shift didn’t happen overnight. The industrialization of agriculture, mass deforestation, and hunting for meat and materials carved away at wild populations bit by bit. Whales, once the largest reservoir of animal biomass, lost two-thirds of their collective weight to industrial whaling. On land, vast herds of elephants and bison were reduced to fragments of their former abundance.

The researchers frame their work not as a tally of species, but as a planetary census of weight—a measure of how much life the Earth now carries, and who carries it.