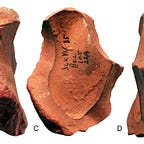

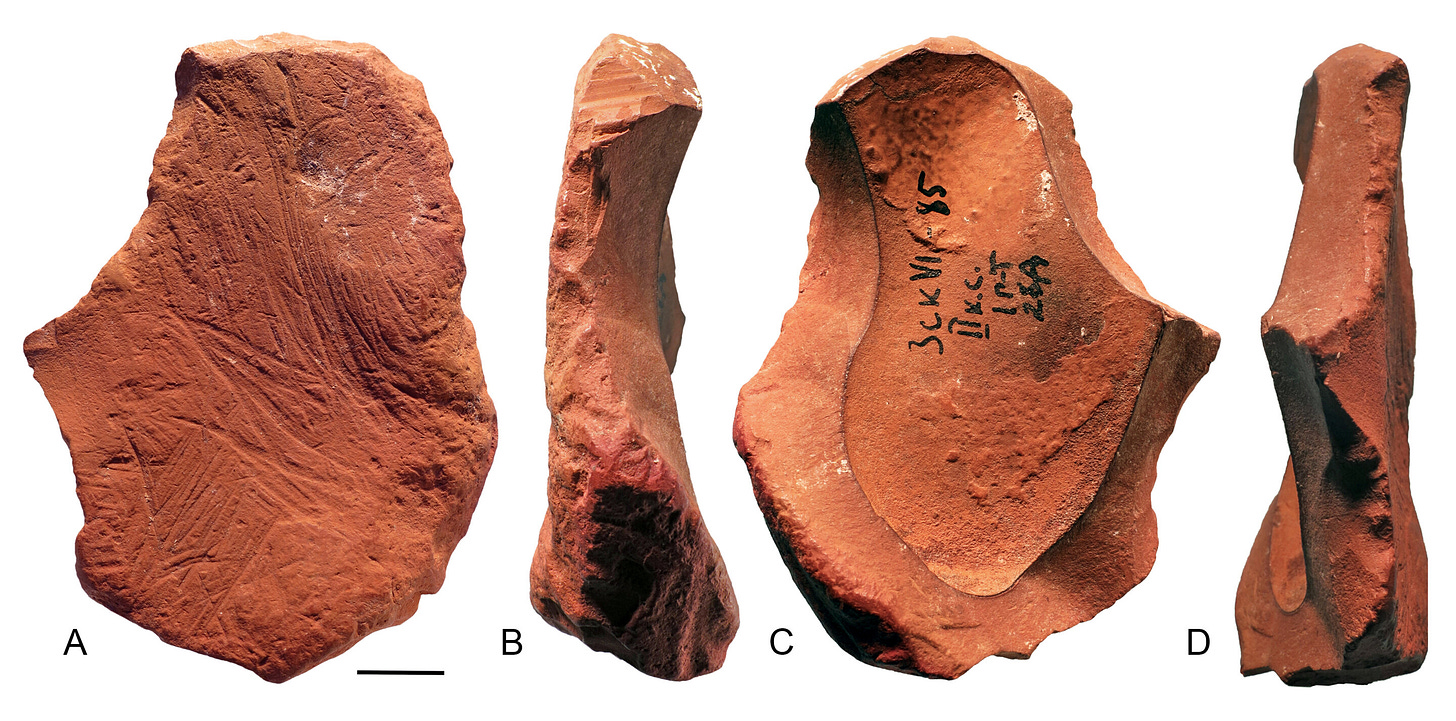

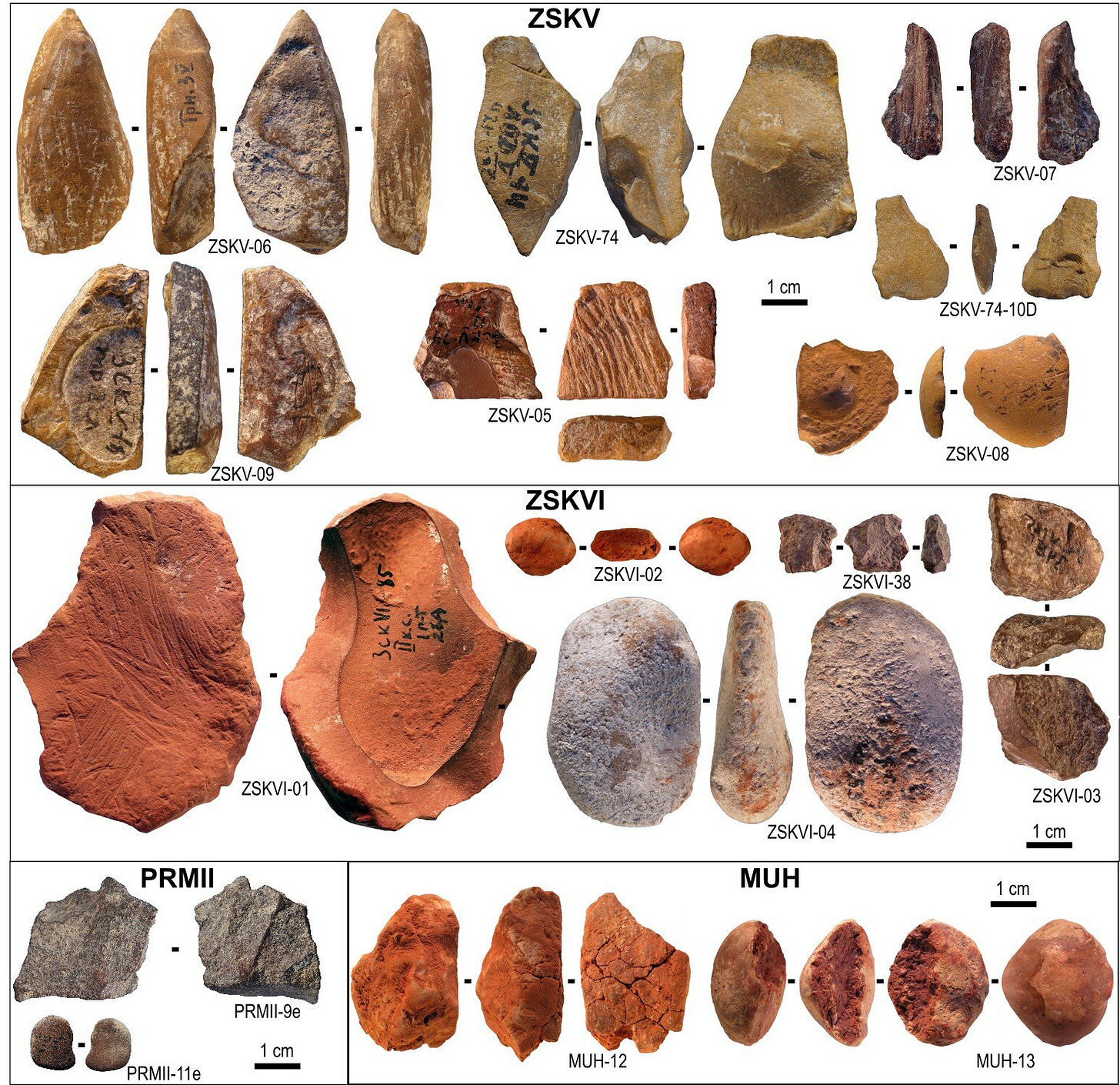

In the low, wind-cut limestone of Crimea, researchers found a sliver of ochre that refuses to behave like a simple mineral fragment. It is tapered, sharpened, and worn in ways that make it hard to see it as anything but purposeful. And its color is not accidental. It is yellow ochre, a pigment favored across prehistory for staining skin, hide, and stone.

The people who shaped it were Neanderthals.

It is a detail small enough to fit between fingertips, yet it pushes at a question that anthropologists have wrestled with for more than a century: How symbolic was Neanderthal life? Did they mark meaning into the world, or merely inhabit it?

A new study led by Francesco d’Errico and colleagues, published in Science Advances,1 argues that these Crimean ochre pieces are not incidental scraps. They are tools made for marking. And they were cared for and resharpened, then used again. Their edges carry the wear of repetition, and their polish hints at hands returning to them over long intervals.

Neanderthals, in this telling, did not simply smash bones and knap stone. They drew, or at least attempted to leave marks that mattered.

“Symbolic behavior is not a sudden switch in the human story,” notes Dr. Helena Strauss, a Paleolithic cognitive archaeologist at the University of Tübingen. “It appears as a thread running through multiple hominin lineages, emerging when social worlds became rich enough to demand symbols.”

That thread, this research suggests, ran through the Micoquian Neanderthals who lived in Crimea roughly between 70,000 and 40,000 years ago.