The Puzzle of Why Humans Cooperate

Of all the traits that define Homo sapiens, cooperation is among the most perplexing. We form alliances with strangers, divide labor, share food, join groups far larger than any primate would tolerate, and sometimes place group welfare above individual gain. The archaeological record hints that these patterns emerged deep in the Pleistocene, yet they remain difficult to explain with simple evolutionary logic. Why invest in others who may not return the favor?

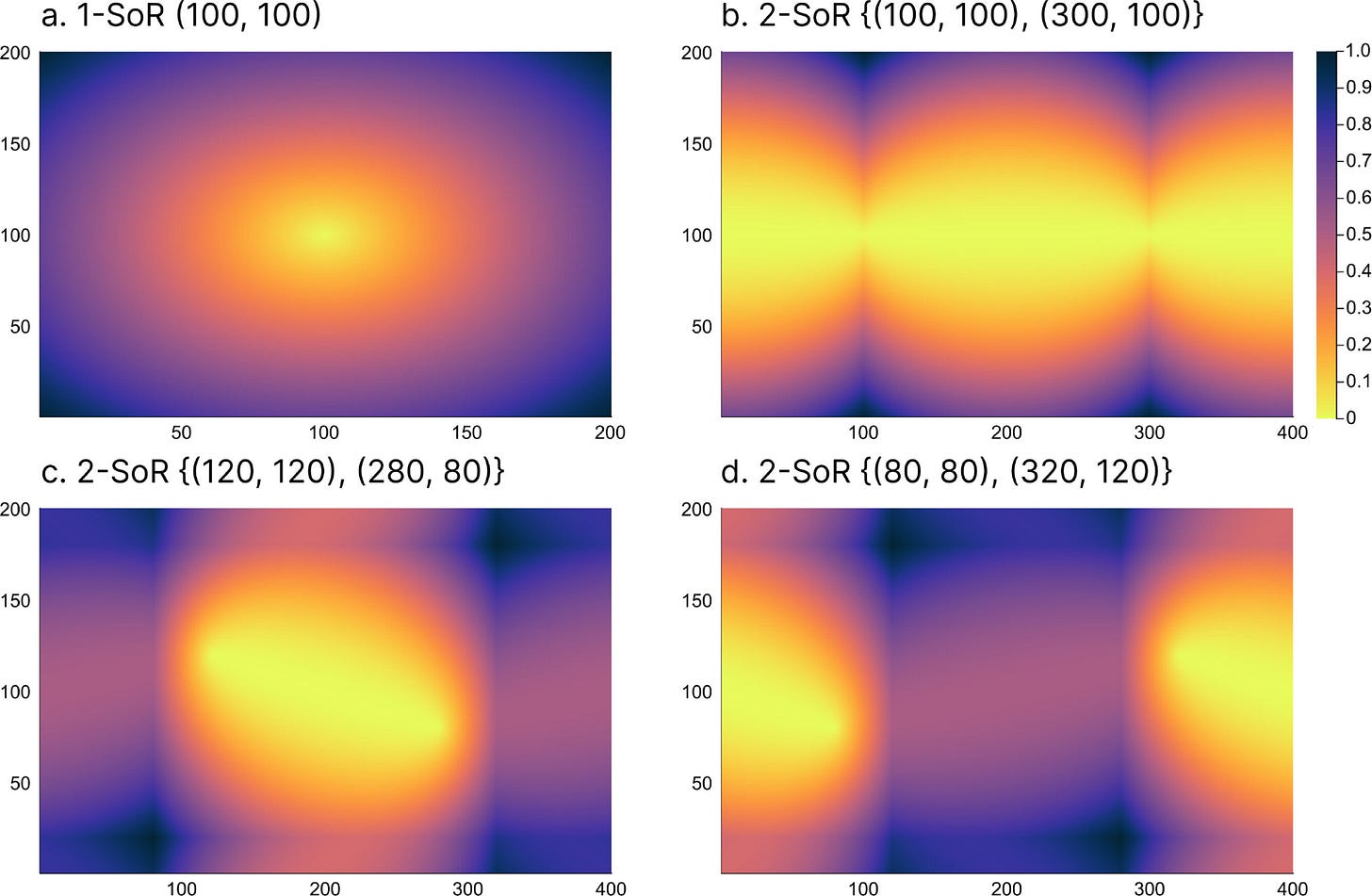

A new study published in Chaos, Solitons & Fractals1 offers a fresh way of thinking about the origins of human cooperation. Rather than framing cooperation as a moral innovation or a product of stable communal life, researchers Masayasu Inaba and Eiki Akiyama from the University of Tsukuba propose that cooperation may actually flourish when the world is unstable. Their agent-based simulations model a simple but powerful idea: when resources shift, people move, and movement disrupts the dominance of selfish behavior.

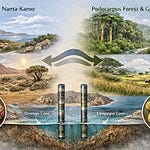

The results point toward a compelling interpretation of the Middle Stone Age environment, one marked by climatic swings, patchy resource landscapes, and frequent migrations. The researchers argue that these ecological pressures may have created the kind of dynamic conditions in which cooperation becomes a winning strategy rather than a vulnerability.

As one anthropologist remarked:

“A static landscape rewards hoarding, but a shifting one punishes it,” says Dr. Elena Rossi of Cambridge University. “Groups that coordinate in uncertain environments gain resilience, and resilience is the ultimate form of survival.”