A New Way to Ask Old Questions

Once, the only way to understand our evolutionary past was to sift through bones, chipped stones, and the occasional fragment of ancient DNA teased from a tooth. Then came full Neanderthal genomes, and suddenly millions of genetic differences between Homo sapiens and our archaic relatives came into view.

But one question has lingered: which of those differences actually matter?

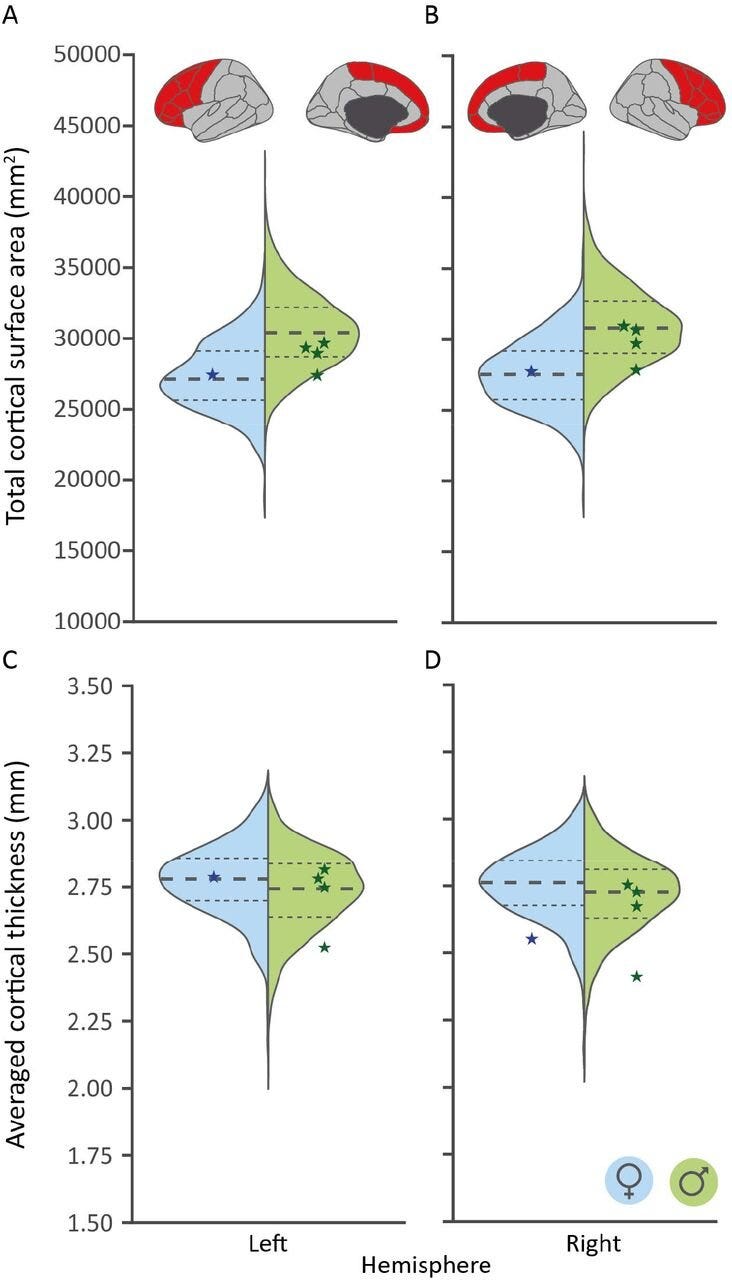

A new study1 from the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics offers a surprising answer. And it does so not by sequencing more fossils, nor by growing brain organoids in a dish. Instead, the researchers turned to hundreds of thousands of living people in a population biobank and asked: what happens when someone today carries a Neanderthal-like version of a gene long assumed to be unique to modern humans?

Their results complicate the simple narrative that a handful of special mutations made our species cognitively exceptional. If anything, they suggest the story is far more subtle.

“Assumptions about dramatic genetic leaps in human evolution require rigorous testing across living populations, not only in experimental systems,” says Dr. Lila Chaudhry, a genetic anthropologist at the University of Toronto.