A Hearth Where There Should Not Be One

Archaeology often moves forward by millimeters. A trowel nicks an unusual surface. A researcher pauses before brushing away another layer. At Barnham, a Paleolithic site tucked into eastern England, those small moments eventually coalesced into something profound: the oldest convincing evidence that ancient hominins were not just tending fire, but making it.

The study, published in Nature,1 pushes deliberate fire-making back to roughly 400,000 years ago. Until now, the earliest secure evidence rested around 50,000 years ago. The gap between those dates is not just chronological. It is conceptual. Fire-making marks a shift from opportunism to mastery, from waiting for lightning to acting with intention.

As one researcher put it:

“A controlled flame is not simply a tool but a signal of planning, knowledge, and social cohesion,” notes Dr. Mara Ellingsen, a Paleolithic fire-use specialist at Aarhus University. “Its presence implies minds capable of anticipating needs long before the moment of need arrives.”

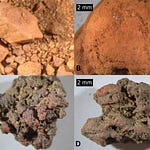

Barnham’s quiet sediments held that signal for hundreds of millennia. What finally brought it to light was a streak of clay, oddly reddened, and a set of flints that seemed fractured by forces far hotter than seasonal brushfires could provide.

Those details opened a path into the deep past, toward a group of early Neanderthals who gathered beside a watering hole and learned to make fire spark on command.

A Landscape That Should Have Erased Everything

The challenge with ancient fire is not that early humans failed to use it. It is that fire rarely leaves a dependable signature. Ash disperses. Charcoal crumbles. Sediment shifts and buries or scatters what a hearth once contained. Many of the earliest traces of fire consist of burned animal bones or small pockets of heated material, ambiguous enough that scholars debate whether people created them or simply capitalized on natural lightning strikes.

That ambiguity has weighed heavily on interpretations of early fire behavior. Humans and premodern hominins clearly exploited fire long before 400,000 years ago. Sites across Africa contain bones charred between 1 and 1.5 million years old, possibly from cooking or waste disposal. But those sites do not demonstrate fire-making itself. They could represent opportunistic use of landscape fires, a behavior well within the reach of hominins who recognized the value of a smoldering branch.

The distinction matters. Opportunistic fire-use depends on ecological luck. Fire-making depends on knowledge. It suggests intentionality, transfer of skills, and an understanding of materials that goes beyond happenstance.

At Barnham, researchers needed to determine whether the burned sediments were natural or cultural. Their analysis took years and relied on geochemistry, field experiments, and painstaking excavation. Layer by layer, they reconstructed a long-vanished pond, a stable gathering point for both animals and humans. What they uncovered contradicted any explanation tied to lightning or wildfire.

Repeated burning occurred at the same spot over decades. The fires reached temperatures well over 700 degrees Celsius. The burn layer was neatly contained rather than spread across the broader landscape.

Those patterns pointed to a hearth rather than a natural blaze. Yet the deciding clue was geological, not thermal.

A Mineral That Should Not Have Been There

Two small fragments of pyrite were the final pieces of evidence. When struck against flint, pyrite produces bright sparks, a technique known ethnographically from hunter-gatherer societies around the world. Pyrite does not occur naturally at Barnham. The nearest known source lies roughly forty miles away.

The presence of imported pyrite changed the conversation. It implied deliberate transport. It also suggested an understanding that certain stones could be used not simply to shape tools, but to create fire itself.

A scholar familiar with Paleolithic pyrotechnology reflected on this point:

“The movement of pyrite into a site where it does not belong indicates a mental map of materials and their properties,” says Dr. Silvio Marro, an archaeologist at the University of Barcelona. “Such knowledge requires teaching and repeated practice rather than chance discovery.”

The combination of pyrite flakes, heat-shattered flints, localized burning, and recurring use transformed Barnham from an ordinary Pleistocene locality into a window on an emergent technology. Fire-making did not appear suddenly. It emerged gradually, likely unevenly, across different populations. Some Neanderthal groups may never have adopted the technique. Others, like those at Barnham, may have practiced it for generations.

The uneven distribution of fire-making is consistent with cultural behavior rather than biological necessity. Knowledge spreads socially, often unpredictably, and can be lost as easily as it is gained.

What Fire-Making Meant for Ancient Hominins

To understand the significance of Barnham, it helps to consider what controlled fire provided. It expanded dietary breadth by rendering tough roots edible and neutralizing toxins. It made meat safer, boosted caloric returns, and allowed groups to occupy cooler environments. Fire also restructured social life. Evenings around a hearth created space for shared attention, storytelling, and planning. Many researchers argue that such gatherings fostered the cognitive landscapes in which language and symbolic culture could grow.

But the Barnham findings push these dynamics further back in time, into a period when early Neanderthals and their close relatives were experimenting with increasingly sophisticated behaviors.

By 400,000 years ago, brain sizes across Europe and parts of Africa were approaching levels comparable to modern humans. Stone tool industries were diversifying. Sites in Britain, Spain, France, and Israel show complex patterns of mobility and resource use.

Fire-making fits within that growing behavioral repertoire.

One paleoanthropologist commented:

“Fire use is both a practical skill and a social performance,” explains Dr. Karen Oduro of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. “Its practice reinforces group identity, teaches coordination, and shapes how time is spent. A controlled fire becomes a focal point through which knowledge and relationships are maintained.”

Fire-making also altered how humans interacted with the landscape. It provided the predictability that nature often denied. A group no longer needed to wait for lightning or wander in search of embers. A spark could be summoned whenever an evening cooled or a meal required cooking.

Some researchers believe that fire-making may have spread widely across Neanderthals, Denisovans, and early Homo sapiens long before 50,000 years ago. Others are more cautious, noting the scarcity of unambiguous evidence.

Barnham does not resolve that debate. But it sharpens the frame through which archaeologists evaluate ancient fire traces and underscores the potential for other early hearths to be preserved in overlooked sediments worldwide.

The Mystery of How Widespread Fire-Making Was

The Barnham findings prompt a broader question: did other populations 400,000 years ago know how to make fire, or was Barnham an outlier?

Some experts propose that the technique may have originated in pockets before spreading socially. Others argue that a lack of archaeological visibility obscures a long and widespread tradition of fire-making. Wildfires can mimic human ones. Human fires can vanish without a trace. The line between evidence and absence is razor-thin.

But the site also reminds researchers that archaeology is often limited by the constraints of preservation and chance. If a small burned patch survived at Barnham, it might survive elsewhere. If pyrite flakes escaped erosion here, they might do so again.

The discovery does not rewrite everything known about ancient fire use, but it forces a reconsideration of how early controlled fire might have emerged, persisted, and circulated among hominin groups.

Related Studies

Roebroeks, W., et al. (2012). “Use of fire in the Lower and Middle Palaeolithic: A review.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1117620109

A foundational analysis of early fire traces and challenges in identifying deliberate fire use.

Sorensen, A., et al. (2018). “Neanderthal fire-making technology inferred from microwear analysis.” Scientific Reports. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-24340-6

Microwear evidence suggesting Neanderthals used pyrite and flint to generate sparks at multiple European sites.

Shimelmitz, R., et al. (2014). “Evidence for the repeated use of a central hearth at Qesem Cave.” Journal of Human Evolution. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2014.06.002

Documents stable hearth use in Israel around 300,000 to 400,000 years ago, offering comparative context for the Barnham findings.

Davis, R., Hatch, M., Hoare, S., Lewis, S. G., Lucas, C., Parfitt, S. A., Bello, S. M., Lewis, M., Mansfield, J., Najorka, J., O’Connor, S., Peglar, S., Sorensen, A., Stringer, C., & Ashton, N. (2025). Earliest evidence of making fire. Nature, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09855-6