A Burial That Refused to Stay Ordinary

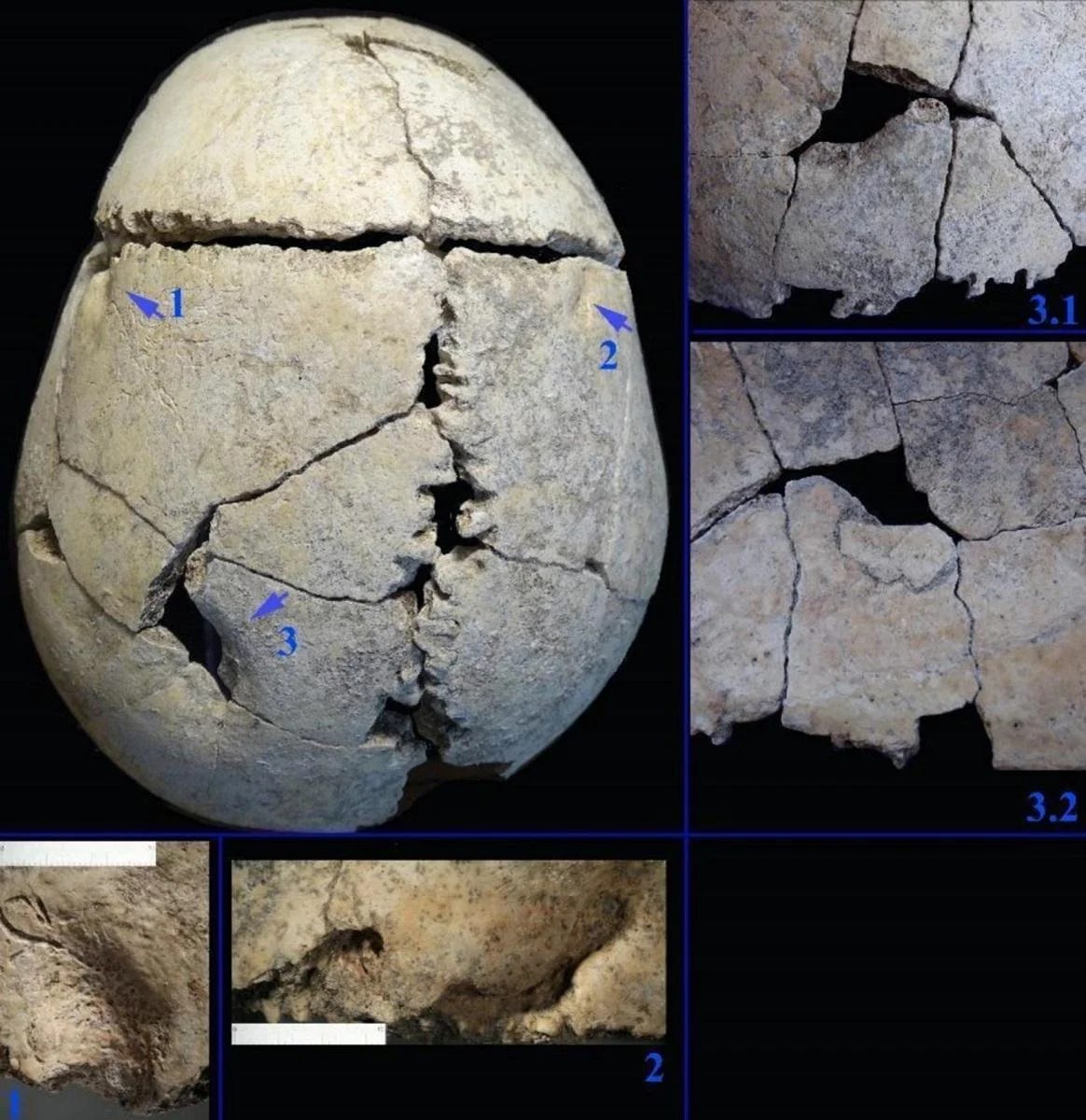

In a Late Eneolithic necropolis near Bulgaria’s Black Sea coast, archaeologists uncovered a grave that looked unremarkable at first glance. No grave goods. A body placed in a tightly flexed position. A pit dug slightly deeper than most of its neighbors.

Then the skull was examined.1

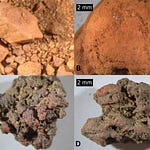

The bones belonged to a young man, perhaps in his late teens or early twenties. He had been tall for his time, with long limbs and the physical markers of a hard childhood marked by episodes of physiological stress. But what set him apart were the injuries. Deep punctures marred the parietal bones of his skull. One wound punched all the way through, leaving a hole that would have exposed brain tissue. Smaller pits clustered nearby, matched by trauma to his legs, shoulder, and arm.

And yet the bone had healed.

New cortical growth smoothed the edges of wounds that should have been fatal. A splinter of bone fused to the inside of the skull, clear evidence that the man lived for months, perhaps longer, after the injury. Whoever he was, he did not die in the moment of violence.

“The pattern of healing makes it clear that the injuries were not perimortem curiosities but lived experiences,” observes Dr. Milena Petrova, a bioarchaeologist at Sofia University. “The skeleton records recovery, not just trauma.”