A Ghost in the Human Family Tree

The domestication of plants and animals has long marked the transition from Pleistocene foraging to Holocene agriculture. But beneath that dramatic shift lies a deeper, older story—one about the complex family tree of hominins that shaped who we are. Long before wheat fields or goat herding, there were Denisovans: an elusive lineage whose DNA echoes through the genomes of modern humans in Asia and Oceania but whose physical remains have remained tantalizingly sparse. Now, recent studies offer our clearest portrait yet of these ancient relatives—an image shaped not by imagination, but by a skull.

From Mystery to Mandible: Fossils of a Lost People

The Denisovans have haunted anthropological literature as a ghost lineage—known not for what they left behind in the archaeological record, but for their genetic fingerprints embedded in the DNA of modern populations. Identified in 2010 from a pinky bone and molar in Siberia's Denisova Cave, these archaic humans rapidly became a source of fascination. But with only fragmentary fossils to go on, scientists struggled to understand what Denisovans looked like, where they lived, or how they interacted with other hominins.

That changed dramatically with a series of papers published in Science (Tsutaya et al., 2025; Fu et al., 2025) and Cell (DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2025.05.040), suggesting that a nearly complete skull—long held in mystery—belongs to a Denisovan. The Harbin cranium, sometimes referred to as "Dragon Man," may be the Rosetta Stone for this ancient population.

The Hidden History of the Harbin Skull

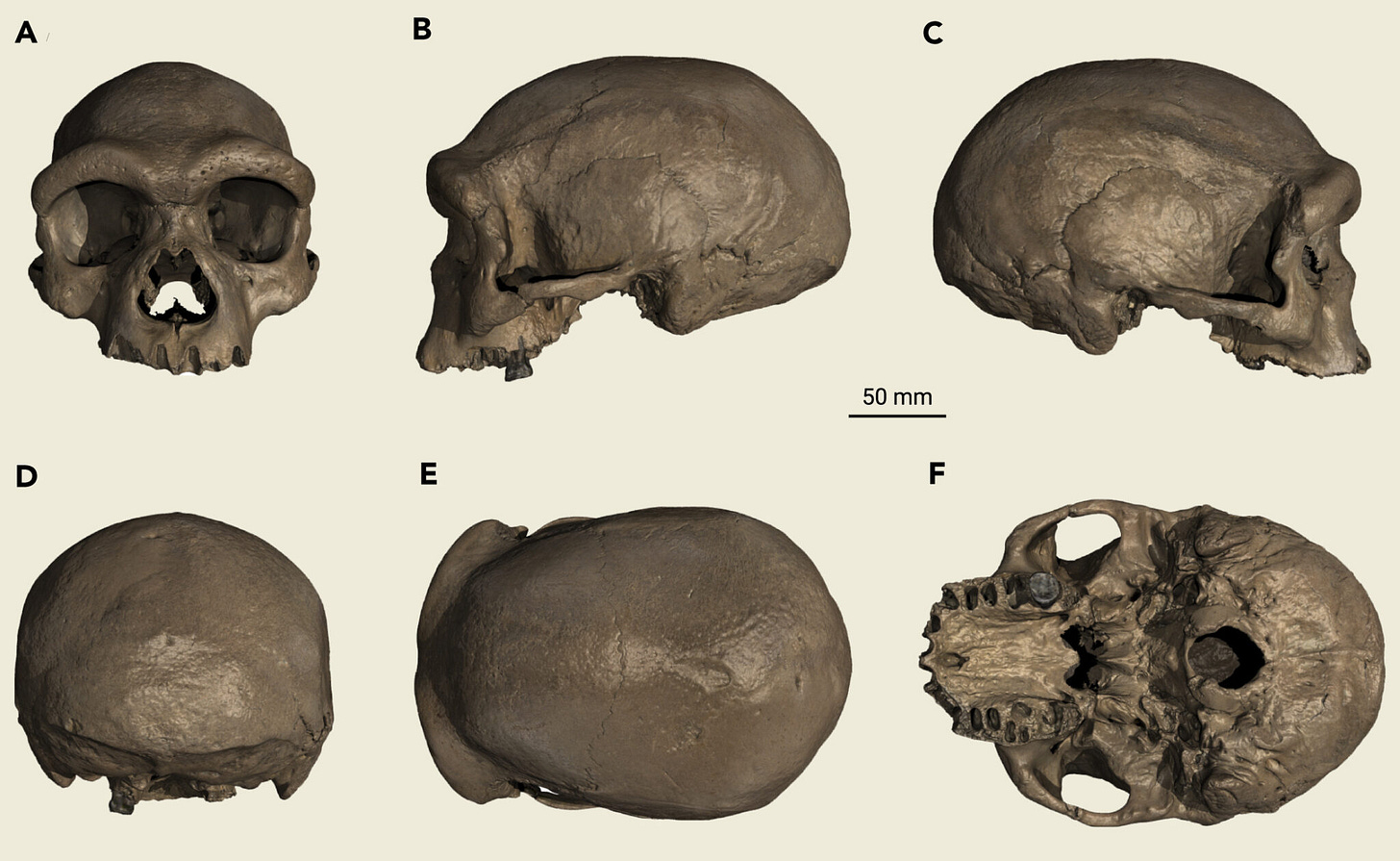

Discovered in the 1930s in northeast China during the Japanese occupation, the skull was hidden for decades to prevent its seizure. Only in 2018 did it come into scientific view. Initially classified as Homo longi, a proposed new species, the skull's unusually robust features, enormous molars, and remarkably well-preserved cranial vault prompted debate about whether it really represented a distinct lineage—or perhaps something more familiar.

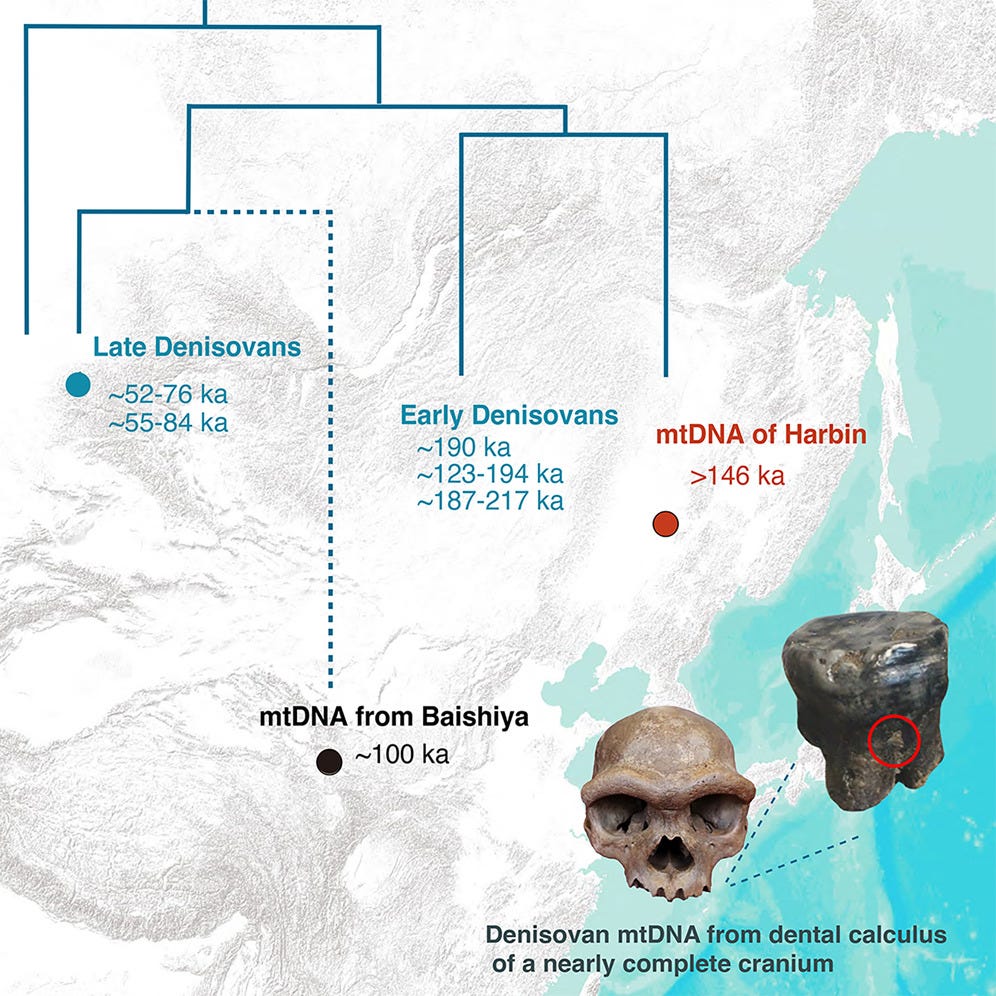

Fu Qiaomei and colleagues applied paleoproteomic and genetic techniques to the skull’s temporal bone and dental calculus. They extracted 95 endogenous proteins, including three unique to Denisovans. The mitochondrial DNA recovered from the tartar also bore strong resemblance to known Denisovan sequences from Siberia, anchoring the Harbin skull within this mysterious lineage.

"This is the first time we have connected a cranium to Denisovans," said evolutionary geneticist Qiaomei Fu.

What Denisovans Looked Like

So what does a Denisovan look like? Harbin 1 had a mosaic of archaic and modern traits: a long, low cranium reminiscent of Homo erectus, a wide, flat face with massive eye sockets, small cheekbones, and large molars. Its brain was big—around 1,420 cc—and its brow heavy. It lacked the domed skull of Homo sapiens and the football-shaped braincase of Neanderthals.

This blend of primitive and derived features complicates tidy narratives of human evolution. Harbin shows that Denisovans were not simply Asian cousins of Neanderthals; they may have been part of a far more diverse population than previously thought, ranging across Asia for hundreds of thousands of years.

A Wider Denisovan World

The Harbin skull isn’t alone. A Denisovan jawbone from Xiahe, Tibet, and a mandible from Taiwan suggest these archaic humans roamed from high-altitude plateaus to coastal regions. Some Chinese fossils—including those from Dali, Jinniushan, and Hualongdong—also share morphological traits with Harbin. The tantalizing possibility is that we already have multiple Denisovan fossils but have lacked the molecular tools to confirm their identity—until now.

The recent Harbin study, using advanced protein sequencing and innovative DNA extraction from dental calculus, pushes the frontier of how we identify archaic humans. As paleogenomics and proteomics converge, the future may reveal a Denisovan fossil record that’s been hiding in plain sight.

The Taxonomic Tangle: Denisovan or Homo longi?

Some researchers, including Xijun Ni, remain cautious. Ni’s team originally proposed the Homo longi classification and raised concerns about modern contamination in the genetic analysis. Others argue that the Denisovan protein variants could have been inherited by early Homo sapiens through interbreeding, rather than indicating direct lineage.

Still, the balance of molecular evidence now tilts toward a Denisovan identity. With protein variants unique to Denisovans and mitochondrial DNA linking the Harbin individual to Siberian samples, the case grows stronger. It may not end the debate over species boundaries, but it sharpens our picture of one very ancient face.

Meeting the Ghost

For over a decade, Denisovans remained a whispered name in the background of our evolutionary story—known only through DNA, their features obscured by time. With the Harbin skull, the whisper becomes a voice. We can now glimpse the brow, the teeth, the very structure of a Denisovan head—and begin to understand their place in our shared past.

As with domestication, the Denisovan revelation challenges simple stories of human progress. Just as agriculture didn’t arise in a single place or moment, our species’ evolution wasn’t a linear path. It was—and still is—a branching, complex web of ancestors and cousins.

References

Fu, Q., Ji, Q., Wu, X., et al. (2025). The proteome of the late Middle Pleistocene Harbin individual. Science, 0, eadu9677. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adu9677

Spengler, R. N., Denham, T. P., & Fuller, D. Q. (2024). Seeking consensus on the domestication concept. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 379(1903), 20240188. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2024.0188

Dal Martello, R., Stevens, C. J., & Fuller, D. Q. (2024). Plant domestication as a multidimensional process: A case study from cereal grain size evolution across Eurasia. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 379(1903), 20240193. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2024.0193

Tsutaya, T., et al. (2025). A male Denisovan mandible from Pleistocene Taiwan. Science, 388, 176–180. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.ads3888