The Elk on the Edge of Time

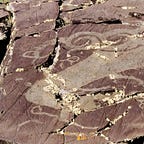

High above the valley floor in the Altai Mountains of western Mongolia, a glacier-polished boulder sits like a sentinel. On its surface, an elk is carved with impressive precision: dense pecking defines its long body, while elaborate antlers curve backward in delicate arcs. Yet something is amiss. Its head tapers into a beak-like shape, its shoulders peak unnaturally, and its legs are vestigial. This elk doesn't belong in any forest.

It is a hybrid—part cervid, part bird—etched by an artist whose world was changing fast1.

Realism and the Early Elk

The story of the elk (Cervus elaphus sibiricus) in Altai rock art spans over 10,000 years. The earliest depictions, dating back to the Late Paleolithic around 12,000 years ago, portrayed elk with impressive realism. These animals stood in profile, their antlers branching upward in recognizable forms. Males and females were sometimes shown together, often alongside now-extinct fauna like woolly rhinos and mammoths. The artists who carved them were observers, not stylists.

In these early works, elk appear solid, grounded, and ecologically rooted. They shared the stone canvas with aurochs, horses, and ostriches—a menagerie of the Ice Age steppe. But over time, this realism gave way to something else entirely.

Shifts in Style, Shifts in Society

By the Bronze Age, the Altai region had warmed and forests had crept higher into the mountains. Human groups reentered these areas, carving new images into stone. Elk began to appear in dynamic scenes, caught mid-stride or pursued by hunters. In one Bronze Age panel, a bowman aims at a large, alert elk; in another, wolves encircle a stag while a human figure looks on.

These compositions are rich in narrative and energy. They reveal a society that hunted elk, revered them, and situated them within a recognizable natural world. Yet by the end of the Bronze Age, something shifted. Elk no longer looked like elk.

Their bodies lengthened. Their heads stretched into beaks. Their antlers grew so ornate they resembled wings or trees. In some cases, the elk took on the crouched form of predators. One image, carved high above the Tsagaan Gol, fuses elk and wolf: a raptor's beak replaces the muzzle, a predator's stance supplants the grazer's poise.

Art Reflecting a World in Flux

What explains this transformation? According to rock art specialist Esther Jacobson-Tepfer, these changes mirror broader environmental and social shifts. The climate cooled again during the late Holocene, and forests receded. Elk withdrew with them, leaving behind grasslands and semi-arid steppe. Pastoralists expanded their mobility, herding livestock through higher elevations. Horses, once only load-bearers, became riding animals.

As people gained speed and range, their relationship to the landscape changed. So too did their art. "Stylization emerges when the artist is no longer copying the animal directly," Jacobson-Tepfer notes. "The image becomes symbolic, disconnected from observation."

"Rather than consulting the natural world around them, the artists turned to portable objects, perhaps those they were carrying on their own persons, and these became the models for a new kind of cultural imagery." —Jacobson-Tepfer (2025)

These stylized elk—exaggerated, adorned, often fantastical—echoed the visual motifs found in portable gold and bronze plaques from elite burials such as those at Arzhan in Tuva. In those contexts, the elk was not prey. It was emblem: of rank, clan, or cosmic order.

When Elk Became Language

The emergence of elk as emblems coincided with the rise of Siberian Scythian cultures and a more stratified, mobile, and horse-dependent way of life. In the Iron Age, riders wearing decorated armor and embroidered garments displayed these stylized animals like sigils. The real animal may have faded from local forests, but it endured on skin, stone, and gold.

"The radical de-naturing of the elk image indicates that earlier frames of reference joining the individual to the phenomenal world had weakened and were falling away, replaced by concerns with social identity and status." —Jacobson-Tepfer (2025)

The rock art tells a story not just of aesthetic change but of cultural reorientation. When the elk ceased to be a real animal and became a vessel of identity, something fundamental shifted in how people imagined themselves.

From Elk to Absence

By the Turkic period, centuries later, the elk had all but disappeared from the rock art of the Mongolian Altai. The forests that once supported them had receded. The people who once depicted them had moved on, visually and perhaps spiritually.

But for a time, the elk served as both witness and metaphor. From Ice Age realism to Iron Age abstraction, its image tracked the evolution of human thought, society, and movement. Across the pecked stones of the Altai, the elk endured—until it didn't.

Related Research

Aruz, J., Farkas, A., Alekseev, A., & Korolkova, E. (2000). The Golden Deer of Eurasia: Scythian and Sarmatian Treasures from the Russian Steppes. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Chugunov, K. V., Parzinger, H., & Nagler, A. (2010). Die skythenzeitliche Fürstenkurgan Arzhan 2 in Tuva. Mainz: Deutsches Archäologisches Institut.

Jacobson-Tepfer, E. (2015). The Hunter, the Stag, and the Mother of Animals: Image, Monument, and Landscape in Ancient North Asia. Oxford University Press.

Barkova, L. L., & Pankova, S. V. (2005). Tattooed mummies from the large Pazyryk mounds: new findings. Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia, 2(22), 48–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aeae.2005.08.005

Jacobson-Tepfer, E. (2025). From monumental realism to denatured beast: The transformation of the elk image in rock art of the Altai Mountains (Mongolia) and its cultural implications. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774325000137