The Face of an Ancient Puzzle

On the rugged, rainforest-covered island of New Guinea, a striking human population carries features that have long puzzled scientists. Their faces bear some resemblance to Sub-Saharan Africans, though their home lies just north of Australia. Their DNA carries traces of the elusive Denisovans. Their archaeological record suggests they were among the first people to reach Oceania. And for decades, their origins have sparked one of the most persistent debates in human evolutionary research: Are Papua New Guineans descendants of a separate early human migration out of Africa?

A new study published in Nature Communications1 makes a strong case that they are not. Instead, it suggests that Papua New Guineans are a sister population to other Asian groups and share in the same major Out of Africa dispersal event that gave rise to all non-Africans.

But the story is far from simple.

A Test Case for Early Human Expansion

The modern human exodus from Africa is usually dated to between 50,000 and 70,000 years ago. But Papua New Guinea presents a wrinkle. Archaeological sites in the highlands date to at least 50,000 years ago, placing humans there around the same time, if not earlier, than in Europe.

This fed a theory known as the First Out of Africa model: that some populations left Africa in an earlier wave and traveled along a southern coastal route into Southeast Asia and Oceania. According to this idea, the ancestors of Papuans may have split from other humans before the ancestors of Europeans and East Asians diverged.

For decades, this remained an open question. Early mitochondrial and Y-chromosome studies did not resolve it. And Papuan DNA carries other complexities: among them, the highest known proportion of Denisovan ancestry in any human group.

In other words, Papua New Guineans represent a test case for how much we really understand about early human migration and contact.

Deep Models and Bottleneck Clues

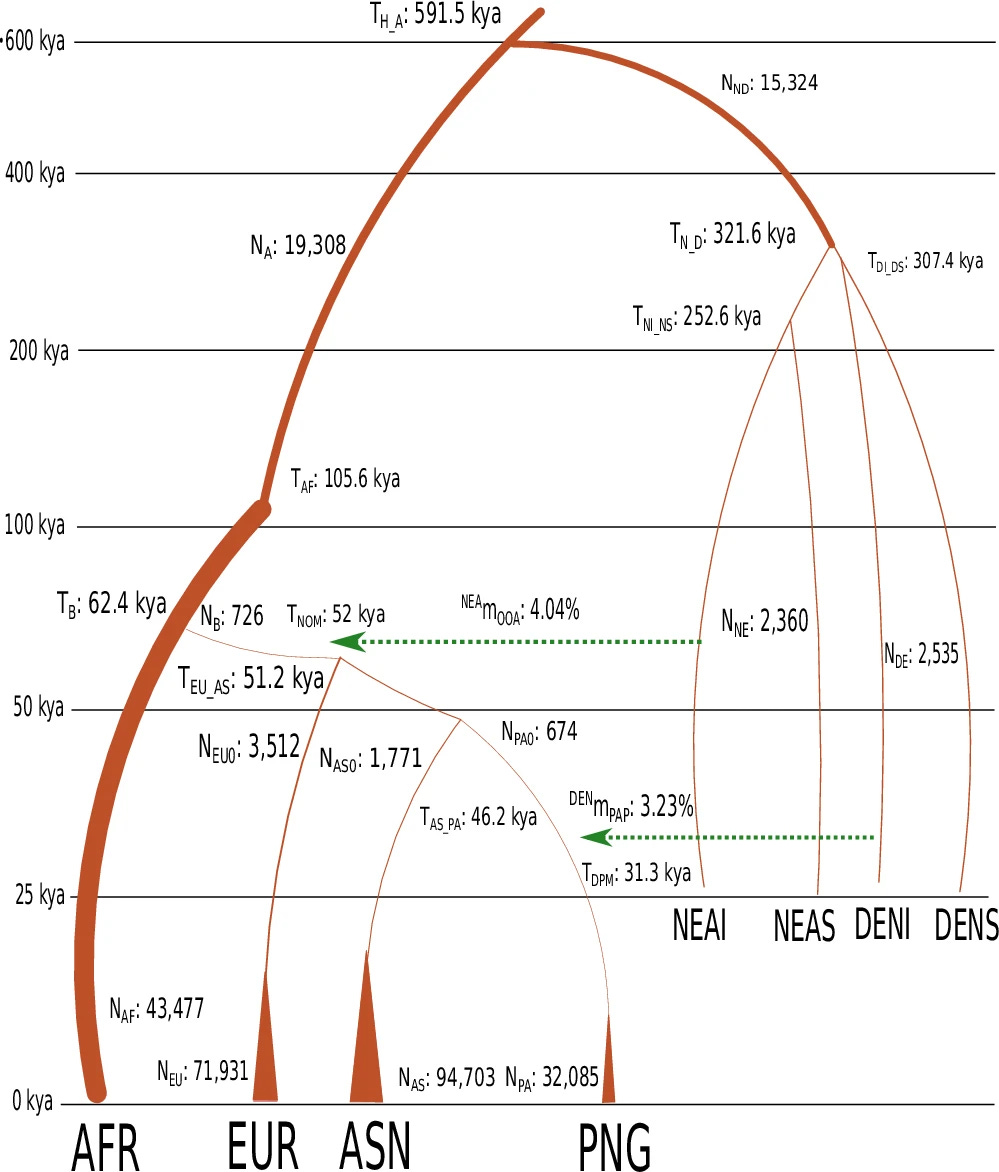

To examine these questions, a team led by Mayukh Mondal, Maria André, and colleagues applied deep-learning neural networks trained on high-quality human genomic data. These models simulate millions of possible demographic histories—births, splits, bottlenecks, migrations—and compare them against the real genetic record.

The findings suggest that a separate early migration is not necessary to explain the Papuan genome. Instead, Papua New Guineans appear to be a sister population to other non-Africans, particularly East Asians. According to the authors:

“Our findings support a model where the ancestors of present-day Papua New Guineans derive from the same Out of Africa event that gave rise to all other non-African populations.”

Yet the story doesn’t end with shared ancestry. The genetic signal of the Papuan population tells of a dramatic bottleneck—a steep drop in population size—that may have occurred after their ancestors reached the island.

“Papuan ancestors likely experienced a severe bottleneck followed by long-term isolation, leading to reduced genetic diversity and elevated levels of Denisovan ancestry,” the study reports.

This prolonged isolation, combined with environmental pressures, likely shaped their unique genetic and phenotypic traits. Adaptation to the tropical environment may have played a role in producing some of the physical similarities with African groups, despite a shared ancestry with Asians.

Denisovan Shadows and Missing Ghosts

One part of the Papuan genome remains distinct: their considerable inheritance from Denisovans, an extinct lineage of archaic humans first discovered in a Siberian cave. While Denisovan ancestry exists in many Southeast Asian and Oceanic populations, it is particularly strong in Papuans, ranging from 4 to 6 percent.

This raises intriguing questions about contact zones and hybridization. Where did these ancient meetings happen? And how often?

At the same time, the study’s results leave little room for a large contribution from a ghost population descended from an earlier migration. If such a population did exist, its genetic footprint appears to have been absorbed, overwritten, or rendered negligible by later waves.

The Importance of Nuance in Deep Time

This study challenges a long-held theory and adds clarity to the human story in Oceania. But it also serves as a reminder that human evolutionary history is rarely linear. Bottlenecks can mimic the signal of ancient admixture. Adaptation can produce physical similarities in distantly related groups. And isolation can preserve ancestral patterns that vanished elsewhere.

Geneticist Mayukh Mondal noted that physical features may not always reflect population history:

“Perhaps adaptations to tropical climates make them look more like Sub-Saharan African groups, even though their genetics clearly link them to other Asian populations.”

What might seem like divergence may simply be persistence under unique conditions.

Related Research

Here are several studies that complement the findings of this work:

Reich, D. et al. (2011). Denisova admixture and the first modern human dispersals into Southeast Asia and Oceania. American Journal of Human Genetics, 89(4), 516–528.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.09.005Skoglund, P. et al. (2016). Genomic insights into the peopling of the Southwest Pacific. Nature, 538, 510–513.

https://doi.org/10.1038/nature19844Malaspinas, A. S. et al. (2016). A genomic history of Aboriginal Australia. Nature, 538, 207–214.

https://doi.org/10.1038/nature18299Bergström, A. et al. (2020). Insights into human genetic variation and population history from 929 diverse genomes. Science, 367(6484).

https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aay5012Jacobs, G. S. et al. (2019). Multiple deeply divergent Denisovan ancestries in Papuans. Cell, 177(4), 1010–1021.e32.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2019.02.035

Mondal, M., André, M., Pathak, A. K., Brucato, N., Ricaut, F.-X., Metspalu, M., & Eriksson, A. (2025). Resolving out of Africa event for Papua New Guinean population using neural network. Nature Communications, 16(1), 6345. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61661-w