The Smallest Clue at the Center of a Megalithic Mystery

It’s easy to be overwhelmed by Stonehenge’s grandeur. The sarsens tower overhead, imposing and silent, while the smaller bluestones crouch in their shadow, quietly holding one of archaeology’s longest-running debates.

Where did these enigmatic blue-gray rocks come from? And more pressingly, how did they arrive on Salisbury Plain?

For decades, the debate has seen two major contenders: deliberate human transport versus glacial delivery during the last Ice Age. The recent study 1of a forgotten fragment known as the “Newall boulder,” excavated from Stonehenge in 1924, may finally tip the scale.

A Fragment Rediscovered

Measuring just 22 by 15 by 10 centimeters, the Newall boulder would be easy to miss. But its story reaches across time and geography.

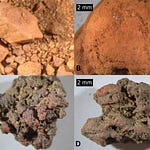

Unearthed by Lt-Col William Hawley nearly a century ago and taken into the possession of R.S. Newall, the stone went largely unexamined for decades. Thin sections were prepared by the Institute of Geological Sciences in the 1970s and the Open University in the 1980s. These were quietly archived at the British Geological Survey and Museum Wales, but never fully analyzed in modern context—until now.

In a 2025 study published in Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, a team led by Richard E. Bevins and colleagues revisited the boulder using a suite of modern tools: mineralogical profiling, petrography, and geochemical fingerprinting.

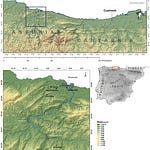

Their conclusion is unequivocal: the Newall boulder matches the Rhyolite Group C from Craig Rhos-y-Felin in Wales, over 200 kilometers west of Stonehenge.

“The geochemical signature was a perfect match,” the authors write. “There was no ambiguity about its origin.”

Not a Casual Glacier Passenger

One of the most persistent counterarguments to human transport has been the glacial hypothesis. Perhaps, some suggested, the bluestones were carried south and east by glacial action during the Pleistocene, left as erratics, and later gathered by Neolithic builders.

But the new study leaves little room for that theory.

No striations typical of glacial abrasion were found on the boulder’s surface. Instead, edge damage was consistent with human action—cutting, shaping, or post-breakage wear. Abrasion likely occurred during burial or exposure, not under tons of moving ice.

“The absence of glacial striations and lack of glacial deposits across Salisbury Plain effectively rules out glacial transport for this and other bluestone fragments,” the authors argue.

There are no known glacial erratics within four kilometers of Stonehenge. Field surveys and sediment records offer no evidence of glacial advance in the area.

One Rock, Many Implications

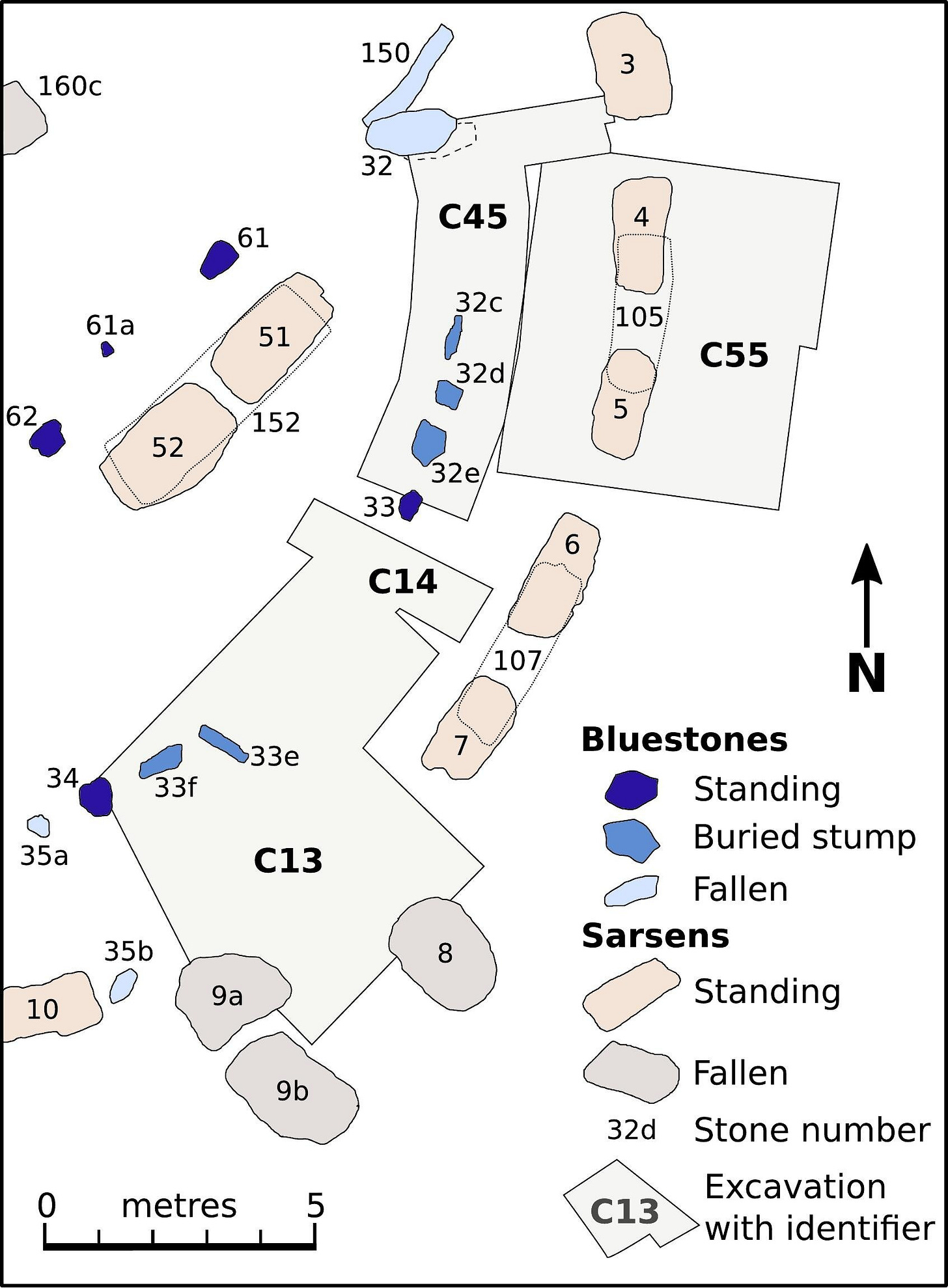

What makes the Newall boulder particularly useful is not just its clear provenance, but its form. Its bullet-shaped profile matches the tops of in situ rhyolite pillars at Craig Rhos-y-Felin, and it resembles the buried stump of Stone 32d at Stonehenge. These consistencies suggest that it may have broken off a larger monolith during transport or installation.

This finding strengthens the argument that Neolithic people moved these stones by deliberate means, likely using sledges, rollers, or waterways over a journey of more than 200 kilometers.

“The simplest explanation is that the Newall boulder is a fragment of a larger monolith, shaped and transported by human hands,” the authors conclude.

A Monument Built by Many Hands, Not Ice

If the Newall boulder is any indication, the builders of Stonehenge had more than megaliths in mind. They moved massive stones not just from nearby Marlborough Downs, where the sarsens originated, but from distant outcrops in the Welsh Preseli Hills.

And they left behind clues, like this modest-sized boulder, embedded in the site’s soil and story.

This is more than a debate about transport mechanisms. It touches on how prehistoric communities mobilized resources, coordinated long-distance travel, and assigned cultural meaning to specific stones.

“The human effort involved in acquiring and moving these stones across such distances cannot be overstated,” said the authors. “It speaks to a remarkable level of planning and organization in the Neolithic.”

Related Research

Here are several studies that expand or intersect with this debate:

Ixer, R. A., & Bevins, R. E. (2011). Craig Rhos-y-Felin, Pont Saeson is the dominant source of the Stonehenge rhyolitic ‘debitage’. Archaeology in Wales, 50, 21–31. https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/library/browse/details.xhtml?recordId=3205771

Parker Pearson, M. et al. (2019). The origins of Stonehenge: On the track of the bluestones. Antiquity, 93(367), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2018.175

Roberts, B. W., & Frieman, C. J. (2021). Archaeological narratives of movement. World Archaeology, 53(3), 329–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2021.1966183

Darvill, T. (2022). Making time: Stonehenge and the Neolithic cosmos. Oxford University Press.

Bevins, R. E., Pearce, N. J. G., Ixer, R. A., Scourse, J., Daw, T., Pearson, M. P., Pitts, M., Field, D., Pirrie, D., Saunders, I., & Power, M. (2025). The enigmatic ‘Newall boulder’ excavated at Stonehenge in 1924: New data and correcting the record. Journal of Archaeological Science, Reports, 66(105303), 105303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2025.105303