Reimagining the Shores of Human Dispersal

Beneath today’s oceans lies a world that once teemed with human life. In the days when glaciers pressed down on continents and sea levels dropped, vast plains and islands now buried beneath the waves provided corridors for migration. Yet for decades, these submerged landscapes—what geographer Jerome Dobson calls aquaterra—have remained largely speculative.

That may be changing.

A new study by Dobson, together with Italian geophysicists Giorgio Spada and Gaia Galassi, reconstructs ancient coastlines around Africa and West Asia with unprecedented precision. Their findings suggest that the narrative of Homo sapiens’ dispersal from Africa may need to account for now-submerged crossings long ignored by archaeological orthodoxy.

“The exciting implication is that a lot of underwater landscapes have archaeological relevance,” Dobson said. “This mapping gives scientists a better shot at finding them.”

Their research, published in Comptes Rendus Géoscience1, uses updated models of glacial isostatic adjustment (GIA)—which calculate how the Earth’s crust deformed under and rebounded from the weight of Ice Age glaciers—to reimagine where ancient coastlines once lay. Paired with genetic and archaeological data, the results suggest that early humans had far more migratory options than previously thought.

When the Sea Was Land

At the peak of the Last Glacial Maximum, around 21,000 years ago, sea levels were over 100 meters lower than today. Across the globe, land bridges and expanded coastlines would have created new possibilities for movement and settlement.

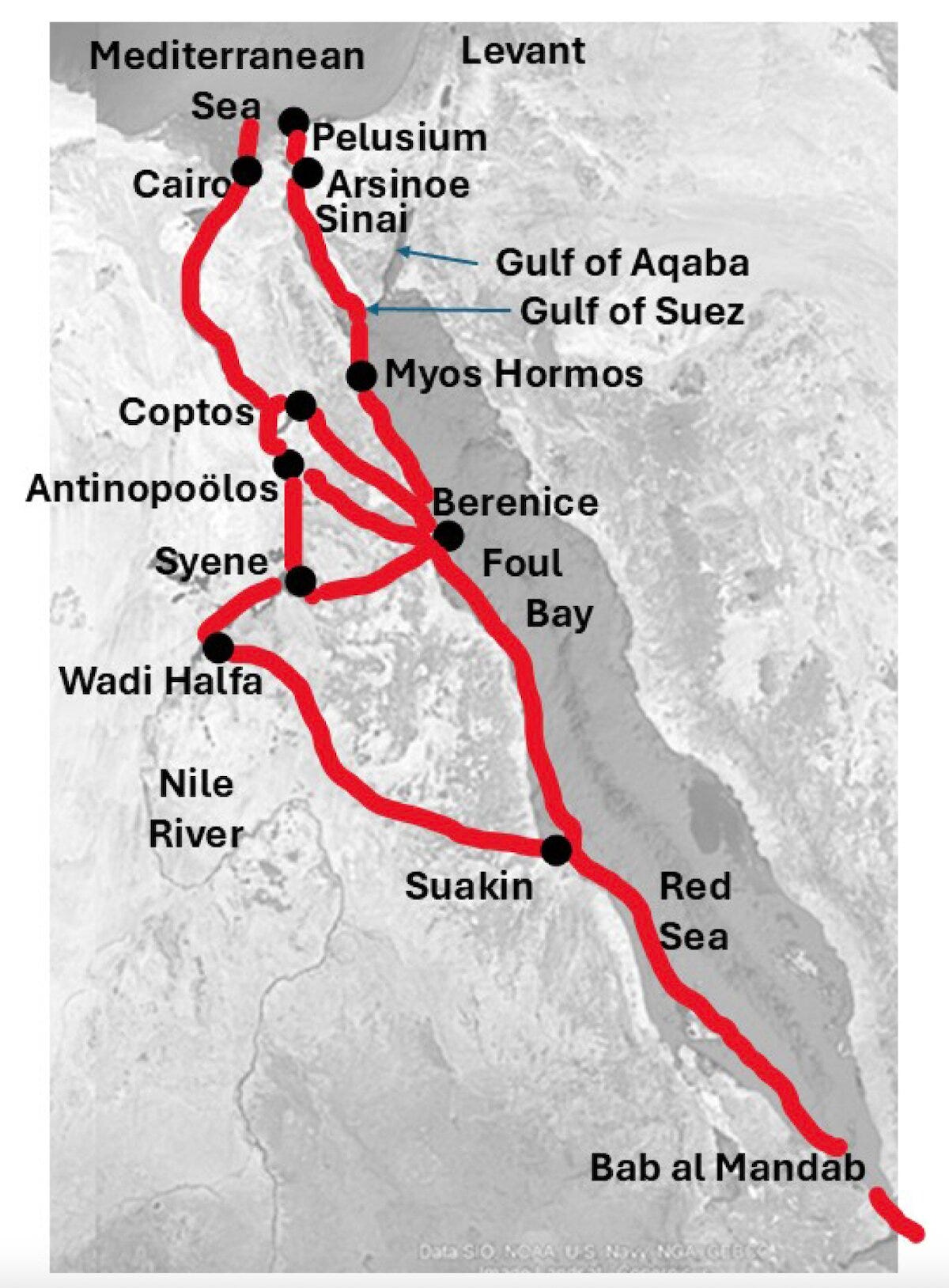

Dobson’s team generated physically accurate reconstructions of these lost coastlines, particularly focusing on northeast Africa, the Levant, and the Red Sea region. These areas have long been assumed to funnel early human populations through a few narrow bottlenecks, particularly the Bab el-Mandeb Strait.

But the study’s refined GIA modeling revealed a more nuanced picture.

“We wanted to generate coastlines that are physically and geophysically correct,” Dobson explained. “Earth’s crust literally warps under the weight of ice sheets.”

That matters because crude sea-level subtraction alone cannot tell researchers where land once stood. The planet’s dynamic surface—sinking under glaciers and rebounding after their retreat—complicates the geometry of ancient migration routes.

A Closer Look at Forgotten Corridors

Among the key findings: the Bab el-Mandeb, long theorized as a vital southern exit point from Africa, may have been less navigable than once believed. While geographically narrow, the strait's coral reefs and treacherous currents would have posed significant challenges for early maritime travelers, especially in periods of high sea levels.

In contrast, the study identifies the Gulf of Aqaba and the Suez corridor as more stable and traversable routes, especially during drier, cooler intervals when lower sea levels exposed continuous land.

The researchers also turned attention to Foul Bay, a relatively unheralded coastal indentation near the Egyptian Red Sea port of Berenice. Their GIA-based reconstructions suggest that this region offered a shorter, more practical route into the Nile Valley than the lengthy Suez crossing.

“Foul Bay would be an important alternative for anyone going from the Red Sea to the Mediterranean or vice versa,” Dobson noted.

DNA as a Compass

To ground their geographic models in real demographic events, the team integrated ancient and modern genetic data. A newly compiled map of ancient human haplotypes—essentially genetic fingerprints of deep ancestry—shows strong evidence of a common origin near present-day Sudan. This supports the idea that northeast Africa was a key launch point for multiple waves of human movement.

The team’s findings suggest a more complex scenario than a single coastal exodus. Instead, multiple staggered movements, shaped by shifting climates, tectonics, and sea-level change, likely occurred.

“We expected people would prefer going up through Foul Bay to the First Cataract of the Nile, which would only be a 300-kilometer route,” Dobson said.

A Map for Future Dives

Perhaps the most lasting contribution of the study is not a single route, but a method. The open-access GIA data developed by Dobson’s team can now help researchers worldwide in reconstructing the submerged geography of other migration corridors. Whether along the Bering land bridge, the Sunda Shelf, or the coasts of South Asia, this approach could shed light on ancient human movements often invisible in terrestrial excavation.

“This is a community resource,” said Dobson. “We wanted to put these reconstructions in investigators’ hands so they can explore their own regions of interest—where humans lived, what the land looked like, and how it changed.”

While much of aquaterra still lies hidden, this work brings its outlines into sharper relief. Somewhere beneath the seafloor lie the campsites, tool scatters, and footprints of people whose migrations shaped the course of human history. The next chapter in the story of human dispersal may well come not from the desert or the cave, but from the coral shelf and the drowned river valley.

Related Research

Lahr, M. M., & Foley, R. A. (2016). Human dispersals and species extinctions in the Late Pleistocene. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 371(1698), 20150242. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0242

Scerri, E. M. L., et al. (2018). Did our species evolve in subdivided populations across Africa, and why does it matter? Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 33(8), 582–594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2018.05.005

Lambeck, K., Rouby, H., Purcell, A., Sun, Y., & Sambridge, M. (2014). Sea level and global ice volumes from the Last Glacial Maximum to the Holocene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(43), 15296–15303. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1411762111

Beyer, R., Krapp, M., & Manica, A. (2021). High-resolution terrestrial climate, bioclimate and vegetation for the last 120,000 years. Scientific Data, 7(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-020-00748-8

Bradshaw, C. J. A., et al. (2021). Minimum founding populations for the first peopling of Sahul. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 5(5), 544–553. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01407-5

Dobson, J. E., Spada, G., & Galassi, G. (2025). Alternative crossings into and out of Africa since 30,000 BP. Comptes Rendus: Geoscience, 357(G1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.5802/crgeos.273