Rethinking the Neanderthal Menu

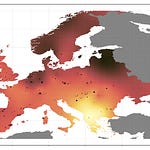

For decades, the heavy nitrogen signatures in Neanderthal bones painted a picture of Ice Age humans as apex predators. The prevailing assumption was that Homo neanderthalensis occupied the highest rung on the food chain—feasting like lions on endless cuts of mammoth, bison, and reindeer.

But a new study published in Science Advances1 by Dr. Melanie Beasley and colleagues suggests that this interpretation may be incomplete—or even wrong.

Neanderthals likely consumed not only fatty cuts of meat but also maggots. The larvae, found thriving in decaying carcasses, may have provided a vital protein source that helped explain their high nitrogen-15 levels (δ15N).

“Neanderthals were not hypercarnivores,” said John Speth, professor emeritus of anthropology at the University of Michigan. “Their diet was different. It’s likely maggots were a major food.”

A New Look at an Old Signal

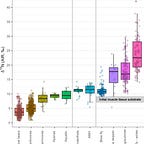

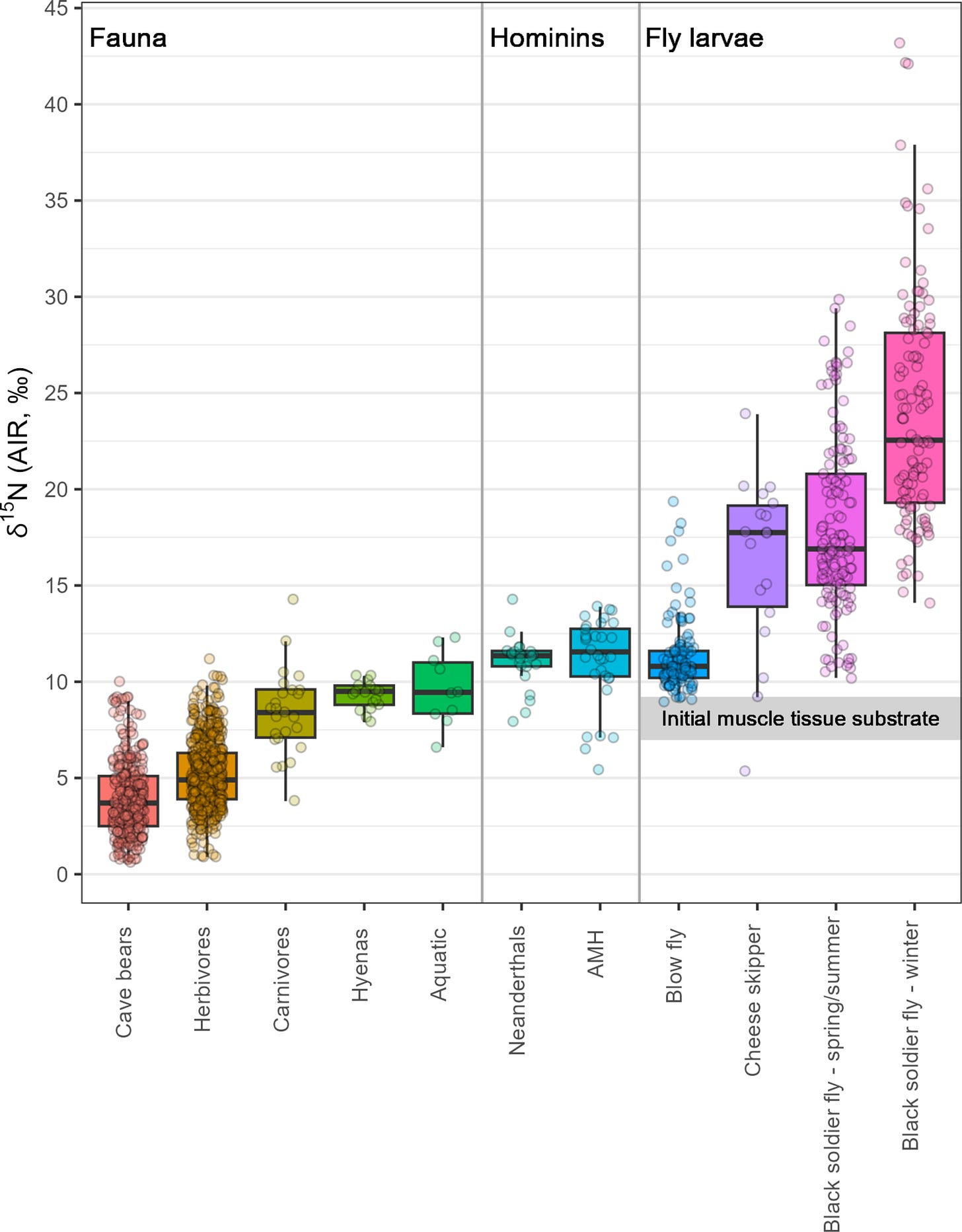

The scientific case for Neanderthal carnivory hinges on stable isotope data. Heavy nitrogen (δ15N) accumulates with each step in the food chain, giving carnivores higher δ15N values than herbivores. Neanderthals consistently show δ15N levels that rival cave lions and wolves.

But humans cannot process as much protein as those predators. The human liver has a hard limit for nitrogen metabolism. Beyond that threshold, the body suffers from protein poisoning, sometimes called "rabbit starvation."

“Humans can only tolerate up to about 4 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight,” Speth noted. “Lions can tolerate two to four times that much.”

So how did Neanderthals maintain such high nitrogen signatures?

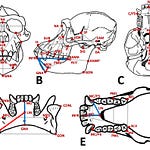

Dr. Beasley, who conducted research at the University of Tennessee’s Forensic Anthropology Center (popularly known as the Body Farm), measured isotopic values in decomposing human tissue and the insects feeding on it. Her results showed that maggots—themselves metabolizing the decaying flesh—became significantly enriched in δ15N.

“Heavy nitrogen rose slightly as muscle putrefied, but was far higher in the maggots,” Beasley reported. “The same process would have occurred in carcasses the Neanderthals stored.”

From Carrion to Cuisine

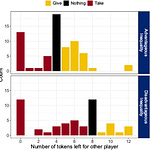

The findings suggest that Neanderthals may have practiced a form of “delayed consumption,” stockpiling meat and returning later to harvest maggots.

This would not have been novel. Many Indigenous groups today, from Australia to South America, regularly eat insects and larvae found in carrion or intentionally fermented foods. These are nutritionally rich, low-effort sources of protein, fats, and essential amino acids.

“Put out a bit of meat, leave it for a few days, then go back and harvest your maggots,” said Karen Hardy, professor of prehistoric archaeology at the University of Glasgow. “It’s a very easy way to get good nutritious food.”

The idea may be off-putting to modern Western sensibilities, but it makes evolutionary sense. Maggots require no additional hunting, can be gathered in bulk, and are dense in the very nutrients Ice Age humans needed.

“It is a no-brainer for Neanderthals,” Hardy added.

Dismantling the Hypercarnivore Myth

The study invites a reassessment of Neanderthal ecology and behavior. Their isotopic signatures may not signal lion-level meat consumption. Instead, they reflect a more varied, clever use of the animal resources available—including the invertebrates that feast on them.

“The idea of Neanderthals as top carnivores was nonsense,” Hardy said. “It was physiologically impossible. This explains those high nitrogen signals in a way that nothing else has done so clearly.”

Far from being brutish mammoth gluttons, Neanderthals appear as pragmatic survivalists, making the most of what the Ice Age landscape had to offer—fresh, fermented, or wriggling.

Related Research

Hardy, K. et al. (2017). “Exploring the role of food processing in human evolution.” Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews, 26(5), 267–277. https://doi.org/10.1002/evan.21538

Bocherens, H. (2011). “Diet and ecology of Neanderthals: implications from isotopic evidence.” Comptes Rendus Palevol, 10(6), 379–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crpv.2011.03.009

Miller, E. T., & McMillan, W. O. (2020). “Insects and the evolution of human diet.” Annual Review of Entomology, 65, 43–61. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-011019-025025

Henry, A. G., Brooks, A. S., & Piperno, D. R. (2011). “Microfossils in calculus demonstrate consumption of plants and cooked foods in Neanderthal diets.” PNAS, 108(2), 486–491. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1016868108

Melanie M. Beasley et al., Neanderthals, hypercarnivores, and maggots: Insights from stable nitrogen isotopes.Sci. Adv.11,eadt7466(2025).DOI:10.1126/sciadv.adt7466