A quiet incompatibility

Roughly 50,000 years ago, in the frozen landscapes of Ice Age Eurasia, Homo sapiens and Neanderthals did something profoundly human: they had children together. Their encounters left a genetic legacy that endures in the DNA of nearly every person of non-African ancestry today. Yet the story of that interbreeding was never one of seamless fusion. Something—biological, environmental, or social—kept the two species from blending fully.

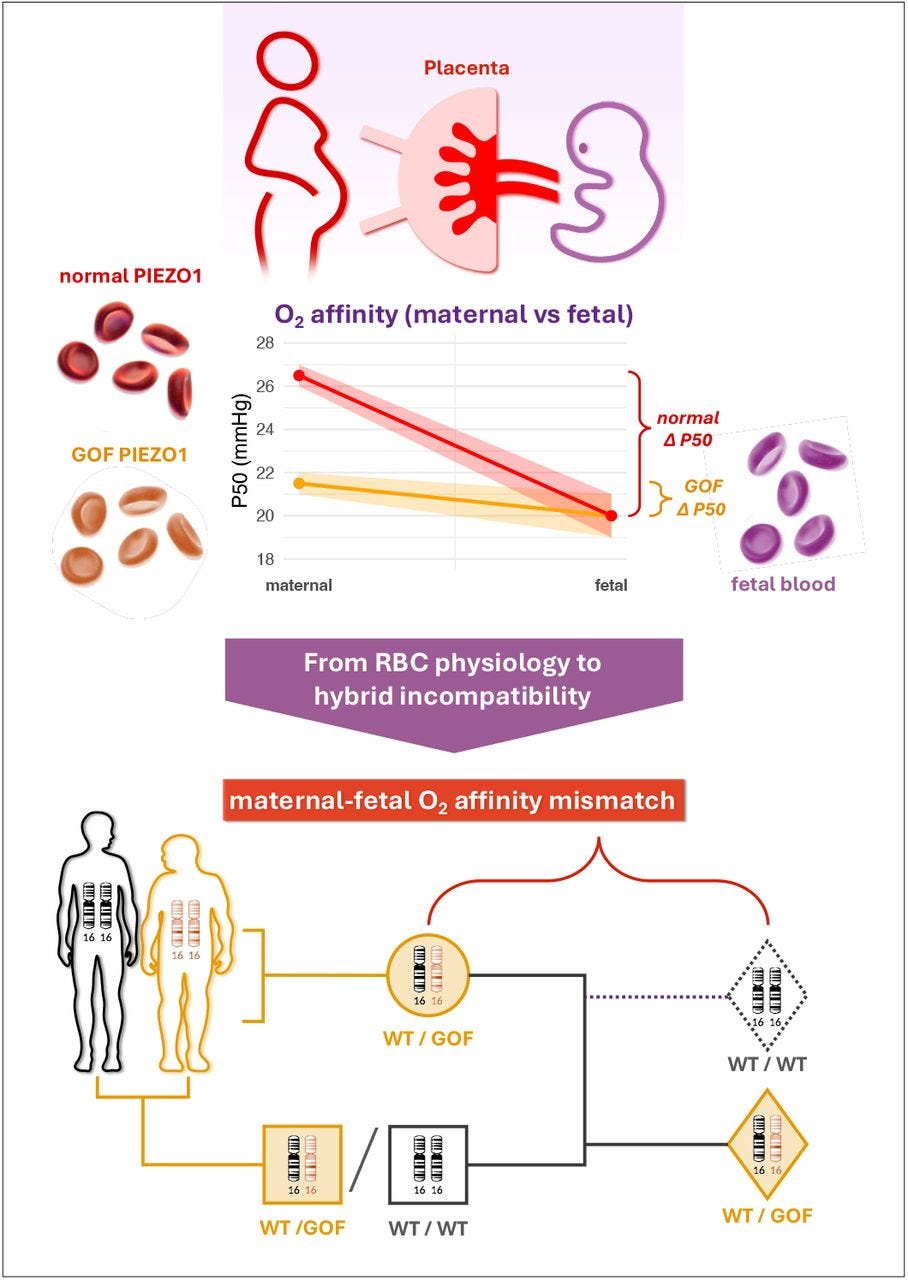

A new study may have identified one of those hidden barriers. Researchers from the University of Zurich, led by Patrick Eppenberger, suggest that an incompatibility in a single gene, PIEZO1, disrupted the balance between Neanderthal mothers and their hybrid offspring. The mismatch, they argue, could have increased the risk of pregnancy loss in women with mixed ancestry, subtly but persistently reducing Neanderthal fertility over generations.

Their hypothesis, posted on bioRxiv in September 2025 (Makhro et al., 2025),1 offers a rare biological lens on why modern humans inherited so little from Neanderthal mothers—and none of their mitochondrial DNA at all.

“When gene flow occurs between distinct species, incompatibilities often manifest not in the first generation but in the next,” says Dr. Helena Moretti, an evolutionary geneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. “It’s a delayed echo of hybridization, and its effects can be devastatingly subtle.”