The Myth of the Pristine Wilderness

For generations, archaeologists imagined Ice Age Europe as an untouched wilderness—a world where humans were too few, too fragile, and too mobile to leave any lasting mark on the land. Dense forests and open grasslands ebbed and flowed with the climate, the thinking went, until the arrival of agriculture finally set human hands to the task of landscape change.

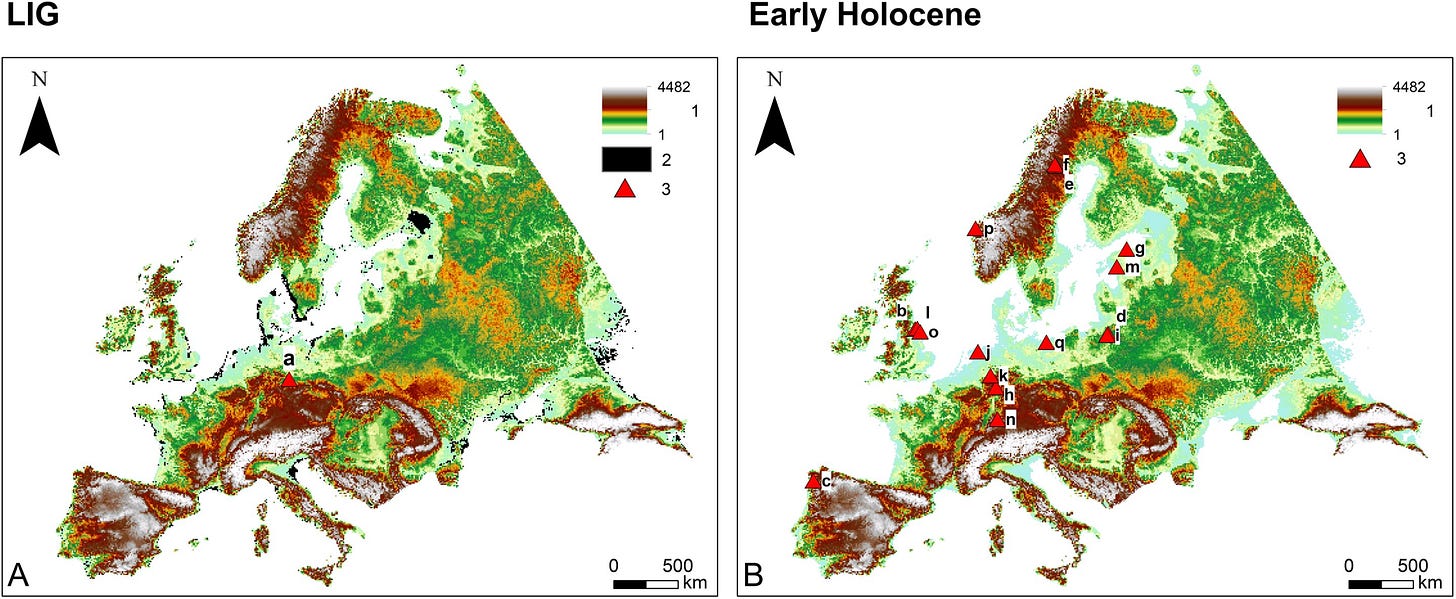

A new study published in PLOS ONE (Nikulina et al., 2025)1 challenges that long-standing myth. Using high-resolution computer simulations and ancient pollen data, an international team of ecologists, archaeologists, and modelers has reconstructed how two distinct groups—Neanderthals during the Last Interglacial (125,000–116,000 years ago) and Mesolithic hunter-gatherers (Homo sapiens) in the Early Holocene (12,000–8,000 years ago)—interacted with the European environment.

Their conclusion is striking: both groups left visible ecological footprints. Long before farmers plowed fields, humans were already engineering the landscape—by hunting, by fire, and by shifting the balance of animals and plants across the continent.

“The idea of a pristine prehistoric Europe simply doesn’t hold up,” said Dr. Jens-Christian Svenning, an ecologist at Aarhus University and co-author of the study. “Even the smallest human communities altered the structure of ecosystems through fire and hunting.”

Two Warm Worlds, Two Human Ecologies

The team’s analysis focuses on two climatic windows separated by over 100,000 years. The first is the Last Interglacial, when Neanderthals were Europe’s sole inhabitants, living among elephants, rhinoceroses, bison, and giant deer. The second is the Early Holocene, when our own species, Homo sapiens, had spread across the continent in the wake of the last Ice Age.

By comparing computer models of vegetation patterns under different combinations of factors—climate, megafauna, wildfire, and human activity—the researchers could estimate the relative influence of each force. To validate their simulations, they matched results against pollen data extracted from lake sediments and bogs, which serve as time capsules of prehistoric vegetation.

When humans were removed from the model, the simulated landscapes failed to align with what the pollen record showed. Only by factoring in human fire use and hunting pressure did the simulations reproduce the ancient data.

“Climate and large animals explain part of the story, but not all,” explained Dr. Anastasia Nikulina, the study’s lead author. “When we added human behavior to the models—fire, hunting, tool use—the patterns made sense.”