A New Kind of Archaeological Trace

When archaeologists excavate ancient graves, they often know who was male, who was female, and sometimes who was a child. But one question has remained almost invisible: which women were pregnant when they died?

Until recently, the only clear evidence came from the rare discovery of fetal bones within a burial. Yet this record is biased by chance—fetuses decay quickly, and their presence depends on burial conditions, not biology. For decades, the most intimate rhythms of reproductive life—menstruation, conception, pregnancy, and postpartum—have remained chemically silent in the archaeological record.

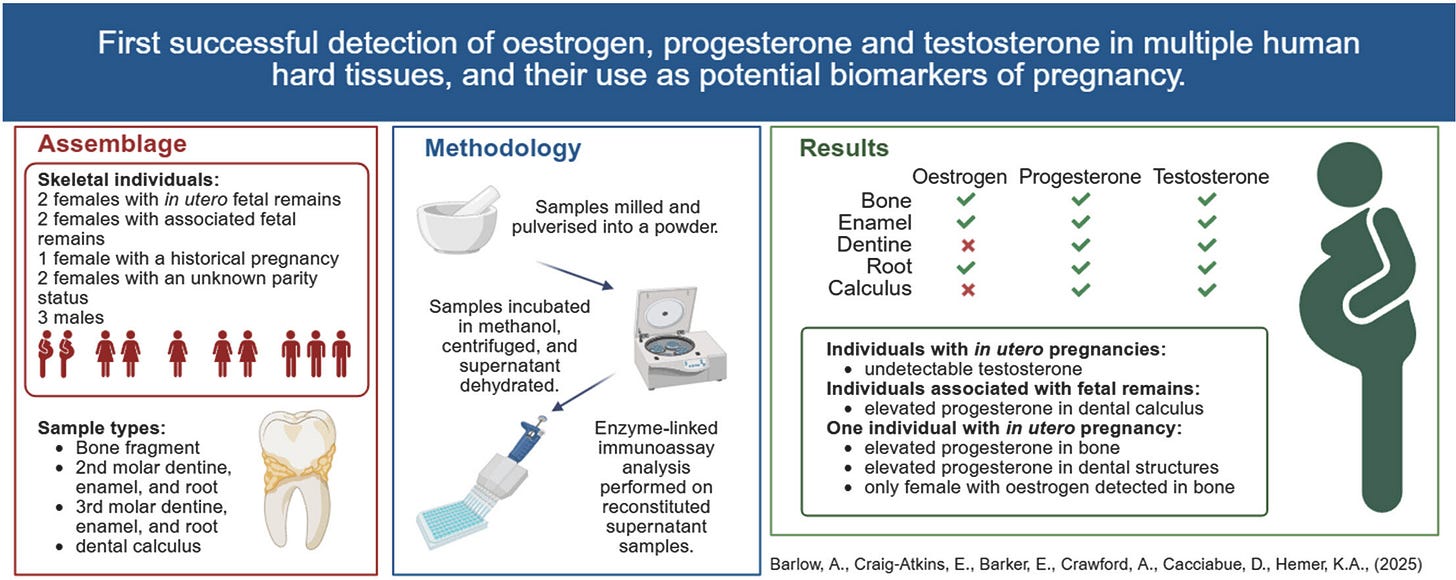

Now, a team of researchers from the University of Sheffield and University College London has managed to recover sex hormones from human bones, teeth, and dental calculus dating back nearly two millennia. Published in the Journal of Archaeological Science (Barlow et al., 2025),1 the study marks the first successful detection of estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone in archaeological hard tissues.

Their findings don’t just refine ancient demographics—they open a biochemical window into the reproductive lives of people who lived centuries ago.

“For the first time, we can read pregnancy directly from the body’s own chemistry, long after soft tissue and DNA have vanished,” said Dr. Alice Barlow, the study’s lead author. “It turns bone and enamel into archives of lived experience.”