A genetic gamble in the Neolithic world

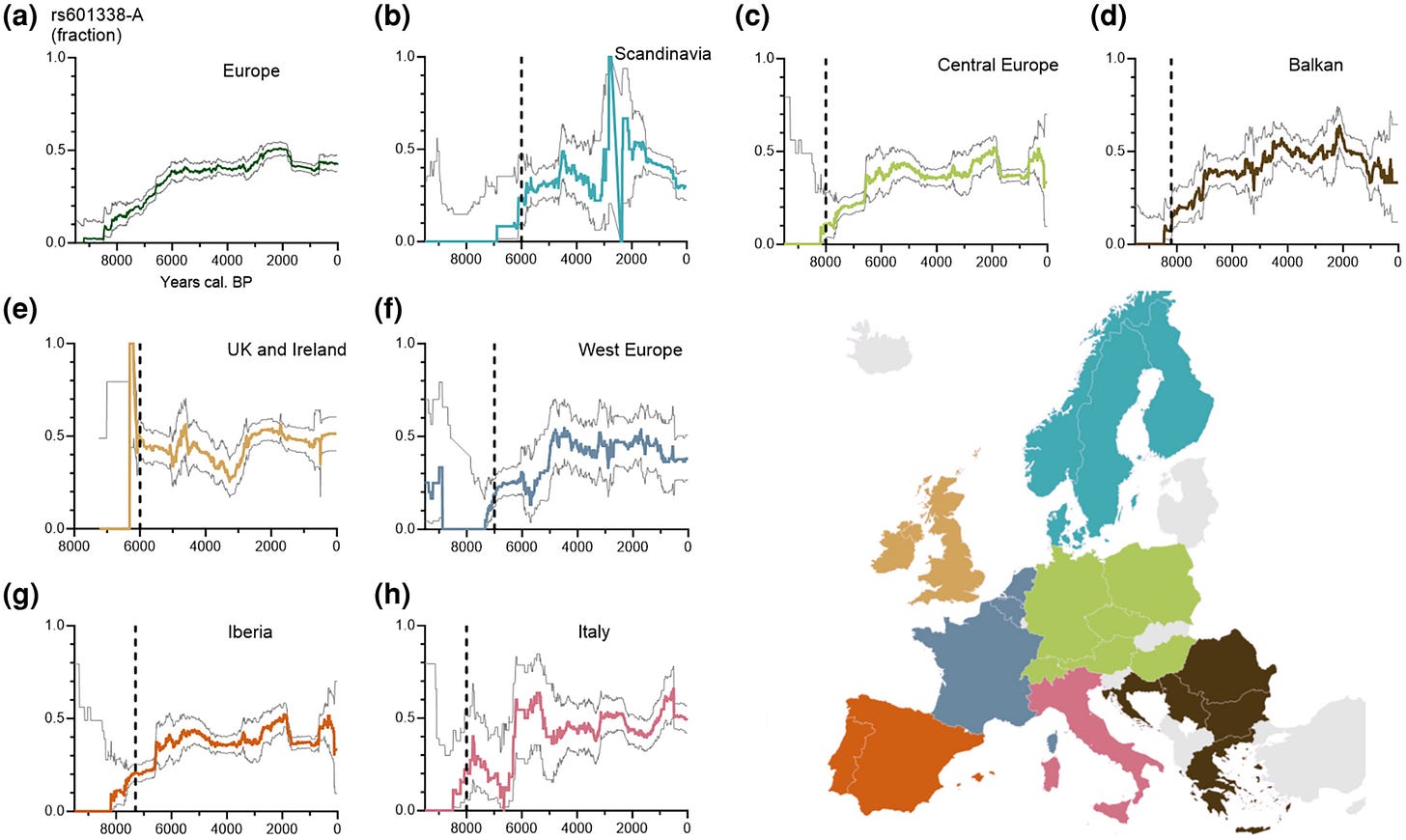

About 8,500 years ago, as small groups of farmers from Anatolia spread across Europe, they brought with them more than seeds and livestock. Hidden in their DNA was a genetic mutation that would quietly reshape human resistance to disease.

The mutation, a single-letter change in the FUT2 gene, stopped the body from decorating gut cells with certain sugar molecules. That minor biochemical shift meant that noroviruses—agents of the dreaded “winter vomiting bug”—could no longer gain entry.

Researchers from Karolinska Institutet, Linköping University, and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology have now traced this variant through more than 4,300 ancient genomes spanning 10,000 years of European prehistory. Their findings, published in Molecular Biology and Evolution,1 reveal how the rise of farming and the crowding of Neolithic life favored people who carried this “defective” gene.

“When people began living close together and with their animals, pathogens found fertile ground,” explains Dr. Hugo Zeberg, a geneticist at Karolinska Institutet. “In that dense microbial environment, even a mutation that broke a small part of human biology could turn into a lifesaver.”