In the soft dunes of Portugal's Atlantic coast, a set of ancient footprints is bringing archaeologists closer to the everyday lives of Neanderthals. Preserved in layers of hardened sand dating to 78,000 and 82,000 years ago, these rare impressions capture a fleeting moment in the lives of an Ice Age family. They walked not far from where waves now crash against the cliffs, threading a steep slope of wet dune, likely hunting red deer. One of them was a toddler.

The tracks, described in a 2025 paper published in Scientific Reports1 by Carlos Neto de Carvalho and colleagues, mark the first confirmed Neanderthal footprints ever found in Portugal. More importantly, they provide direct evidence of family-based subsistence behaviors in coastal landscapes long thought to be marginal in Neanderthal ecology.

"The footprints suggest coordinated movement up and down a dune slope, consistent with the behavior of a social group rather than isolated individuals," the authors write.

A Snapshot in Sand

The footprints were discovered at two sites: Praia do Telheiro, with a single track dated to roughly 82,000 years ago, and Monte Clérigo, where multiple individuals left their mark in a single moment around 78,000 years ago. Both sites preserve fossilized surfaces of ancient dune systems, part of the Pleistocene coastline exposed along Portugal’s Algarve region.

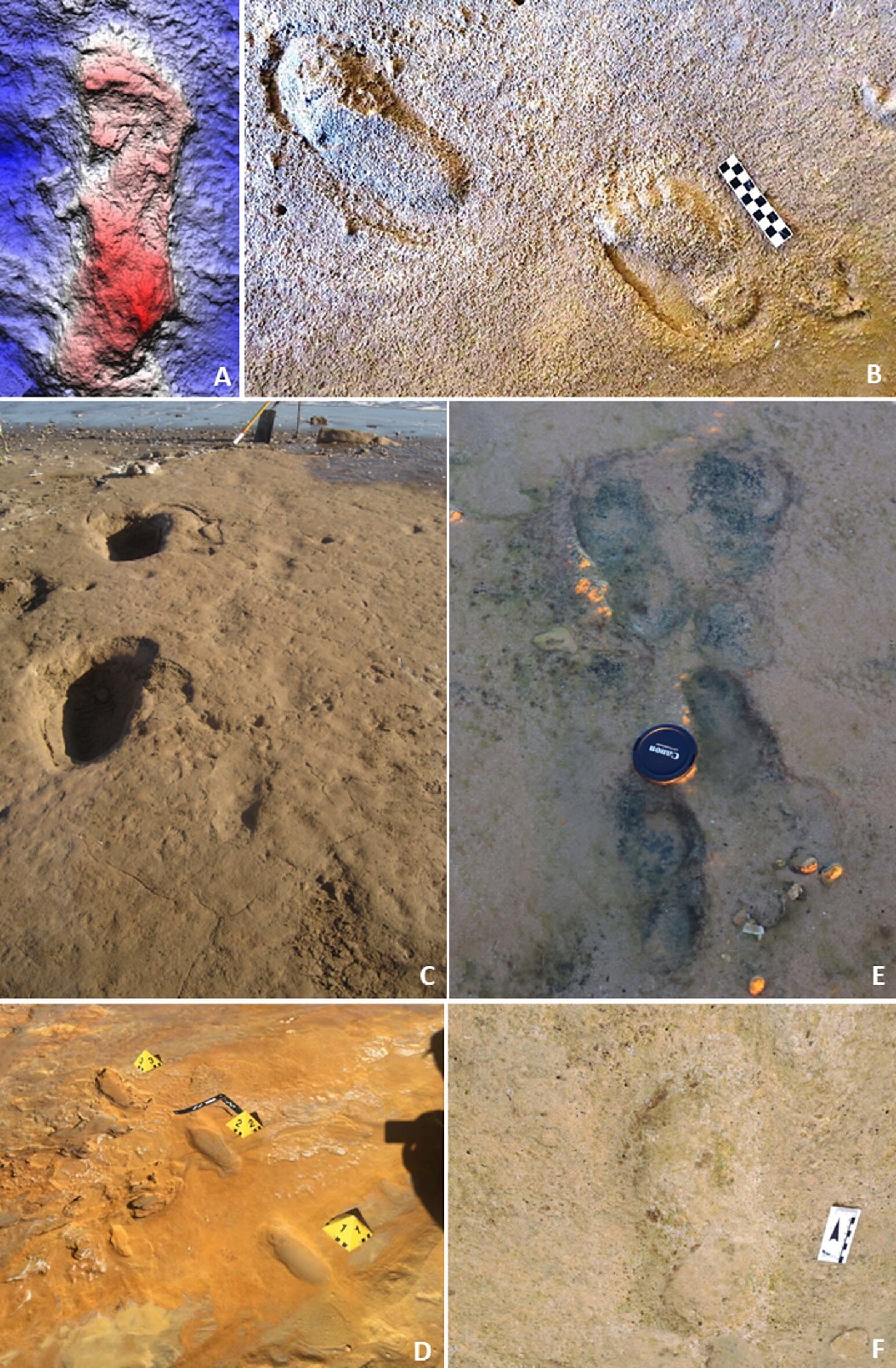

Three individuals left ten footprints at Monte Clérigo. Based on the size and shape of the prints, the trackmakers included an adult male, a child aged seven to nine, and a toddler likely under the age of two. The adult's stride shortened as he climbed, and increased as he descended, a pattern typical of slope negotiation.

The smaller footprints preserve even more than movement: they suggest posture and play. One impression shows only the ball and toes, hinting at a child planting their foot and dragging off. Another has an unusually rounded heel and faint traces of toes. These subtleties allow paleoanthropologists to estimate not only age and body size, but also relative group motion.

Beach Hunts and Biodiversity

Red deer tracks crisscross the same surface. In one case, a Neanderthal footprint overlaps the deer track, providing a relative timestamp. Dunes, with their slopes and blind spots, are ideal for ambush hunting. Researchers believe the individuals were engaged in a hunt. But unlike the stereotypical image of burly males stalking game, this scene included children.

While the youngest may have simply been carried, the presence of multiple age groups suggests that Neanderthals brought family members along as part of mobile foraging groups. The tracks may even point to a temporary campsite nearby.

These new sites support a growing consensus that Neanderthals used coastal zones extensively. They were not merely inland hunters; they exploited diverse ecological niches. Marine resources, shorebird eggs, shellfish, and seasonal movements between coast and interior likely enriched Neanderthal lifeways.

A Wider Pattern

The Monte Clérigo and Telheiro footprints now join a select but growing body of evidence across Europe. Sites such as Le Rozel in France, Matalascañas in Spain, and Theopetra Cave in Greece have yielded similarly rare but revealing traces of Neanderthal feet. Most consist of just a few prints; Le Rozel is the standout, with nearly 600.

What makes the Portuguese sites notable is their coastal setting, steep dune slope, and the presence of very young individuals. This provides a rich behavioral context. The geology of the dunes, preserved under favorable sedimentary conditions, captured not just direction and gait but subtle shifts in pressure and balance. These tracks preserve pauses, slips, and pivots that hint at conscious movement across a dynamic surface.

"Footprints are behavior made visible," the researchers write, "a record of locomotion and intention."

Such ichnological data, when paired with faunal remains and tools, allows archaeologists to move beyond typology and into social narrative. At Monte Clérigo, it is now possible to imagine a father cresting the dune, child in tow, scanning for movement in the brush.

Ancient Feet, Modern Tools

To document the trackways, the team employed high-resolution 3D photogrammetry, stratigraphic mapping, and optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating. The sediment, a carbonate-cemented eolianite formed from ancient dune sand, preserved the impressions with remarkable clarity.

The scientists calculated stride lengths, footprint depth, and slope angle to estimate walking speed. One adult was ascending the dune at about 2.5 kilometers per hour. Another descended at over 8 kilometers per hour, suggesting a hurried pace — possibly pursuit. The smallest footprints reflect shorter stride lengths, lower mass, and unsteady balance consistent with toddlers.

Together, these data provide a biomechanical snapshot: how Neanderthals moved, adapted to terrain, and possibly hunted.

The Coastal Edge of Humanity

Though Neanderthals are often seen through the lens of rugged inland caves, their footprints remind us that they were, at times, children of the shore. The Portugal tracks highlight their capacity to use dune landscapes for travel and subsistence, and to organize social life in complex terrain.

"The co-presence of adults and young individuals in challenging topographies suggests that care, teaching, and cooperation were integral to Neanderthal group life," the study concludes.

At the edge of the continent, under layers of ancient sand, the moment still lingers.

Related Research

Duveau, J., et al. (2019). "The composition of a Neandertal social group revealed by the hominin footprints at Le Rozel (France)." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(39), 19409–19414. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1901789116

Mayoral, E., et al. (2020). "A Pleistocene hominin footprint from the Matalascañas Trampled Surface (Huelva, SW Spain)." Quaternary Science Reviews, 247, 106610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106610

Günther, L., et al. (2022). "Paleoichnological evidence of Neanderthal and faunal activity in a coastal dune environment (Cape Trafalgar, SW Spain)." Quaternary Research, 103, 91–109. https://doi.org/10.1017/qua.2021.24

Duveau, J., et al. (2022). "Estimating age and stature of Pleistocene footprints using modern morphometrics." Scientific Reports, 12, 1044. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-04854-9

de Carvalho, C. N., Cunha, P. P., Belo, J., Muñiz, F., Baucon, A., Cachão, M., Figueiredo, S., Buylaert, J.-P., Galán, J. M., Belaústegui, Z., Cáceres, L. M., Zhang, Y., Ferreira, C., Rodríguez-Vidal, J., Finlayson, S., Finlayson, G., & Finlayson, C. (2025). Neanderthal coasteering and the first Portuguese hominin tracksites. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 23785. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-06089-4