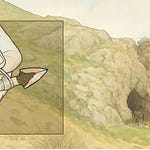

In a quiet crevice of the Catalan Pyrenees, at an altitude where air grows thin and the modern world recedes, a piece of bone has begun to speak. This fractured rib, discovered in the Roc de les Orenetes cave, belonged to a person who lived over 4,000 years ago. What makes the bone remarkable is not simply its antiquity, but the evidence it carries: a flint arrowhead still embedded in its curve. The wound was not fatal. The bone healed.

Archaeologists say1 the victim survived the violence, carrying a stone projectile in their chest to the end of their days. And in doing so, that person also carried a story—a record of conflict in one of the most remote corners of prehistoric Europe.

A Cave of Bones at 6,000 Feet

Roc de les Orenetes lies more than 1,800 meters above sea level in the northeastern Spanish Pyrenees. Since 20192, archaeologists led by Carlos Tornero of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona have excavated the cave, uncovering a remarkable funerary deposit: more than 1,000 human bones, representing at least 51 individuals. Radiocarbon dating places the use of the site between 4,100 and 4,500 years ago, during the Early Bronze Age.

The cave was no isolated curiosity. Rather, it functioned as a high-altitude mortuary site for a community that lived in, or moved through, these mountains. According to bioarchaeologist Miguel Ángel Moreno of the University of Edinburgh, who co-authored a recent study of the remains, this population was not simply climbing for resources or refuge. They were also navigating interpersonal violence.

"This evidence represents recurrent violent behavior and evidence of interpersonal violence located at the highest altitude of the Pyrenees," the researchers wrote.

At least six individuals showed signs of lethal conflict. Trauma was concentrated in the upper body: blows to the ribs, fractures in the forearms, and in one case, a probable amputation. These were not hunting accidents. They were personal.

The Arrow That Stayed

Among the many injuries documented at Roc de les Orenetes, one stood apart. A rib bearing an embedded flint arrowhead had partially healed. This means that the victim—whose age and sex have not yet been determined—survived the initial trauma, living with the projectile in their body for an extended period.

It is a rare find in European prehistory. Most arrow injuries documented archaeologically result in death. The living testimony of this healed wound shifts the narrative. It suggests that life, and possibly medical care or community support, continued after violence.

Future microtomography, chemical, and genomic analyses are planned to investigate not only the exact nature of the injury, but also who this person was and what role they may have played in the community. Researchers at the National Research Centre on Human Evolution in Burgos and labs in Barcelona and the United States are collaborating on the analyses.

Conflict at Altitude

The Roc de les Orenetes burial assemblage invites reconsideration of what highland life looked like in the Bronze Age. At over 6,000 feet above sea level, these people were not merely struggling to survive. They were burying their dead with care and carrying out social lives that included alliance, conflict, and ritual.

The evidence of healed trauma and repeated acts of violence within this community complicates earlier assumptions that mountain groups were peripheral to broader regional dynamics. Instead, it appears they were entangled in systems of rivalry, resource management, and perhaps even warfare.

"Even in the most rugged geographic conditions, small-scale conflicts clearly arose and resulted in injury and death," the team noted.

A New Line of Inquiry

The embedded arrowhead now serves as both a biological and cultural artifact. It tells of a specific encounter: a blow struck, a rib broken, a life continued. But it also broadens the archaeological narrative of Bronze Age Europe. Violence was not confined to lowland power centers or emergent chiefdoms. It occurred at altitude, in places where communities still gathered, hunted, and honored their dead.

And while we do not know whether the person with the pierced rib returned the favor in battle or lived quietly after the wound, the bone itself tells us they endured.

Further Reading

Schulting, R. J., & Wysocki, M. (2005). "Injuries and violence in Neolithic Britain: Evidence from the skeletal record." Oxford Journal of Archaeology, 24(2), 115–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0092.2005.00231.x

Robb, J. (1997). "Violence and gender in early Italy." Current Anthropology, 38(3), 350–57.

Arrowhead embedded in a human rib reveals prehistoric violence in the Pyrenees over 4,000 years ago. (n.d.). Iphes.Cat. Retrieved July 15, 2025, from http://comunicacio.iphes.cat/eng/news/new/860.htm

Moreno-Ibáñez, M. Á., Saladié, P., Ramírez-Pedraza, I., Díez-Canseco, C., Fernández-Marchena, J. L., Soriano, E., Carbonell, E., & Tornero, C. (2024). Death in the high mountains: Evidence of interpersonal violence during Late Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age at Roc de les Orenetes (Eastern Pyrenees, Spain). American Journal of Biological Anthropology, 184(1), e24909. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.24909