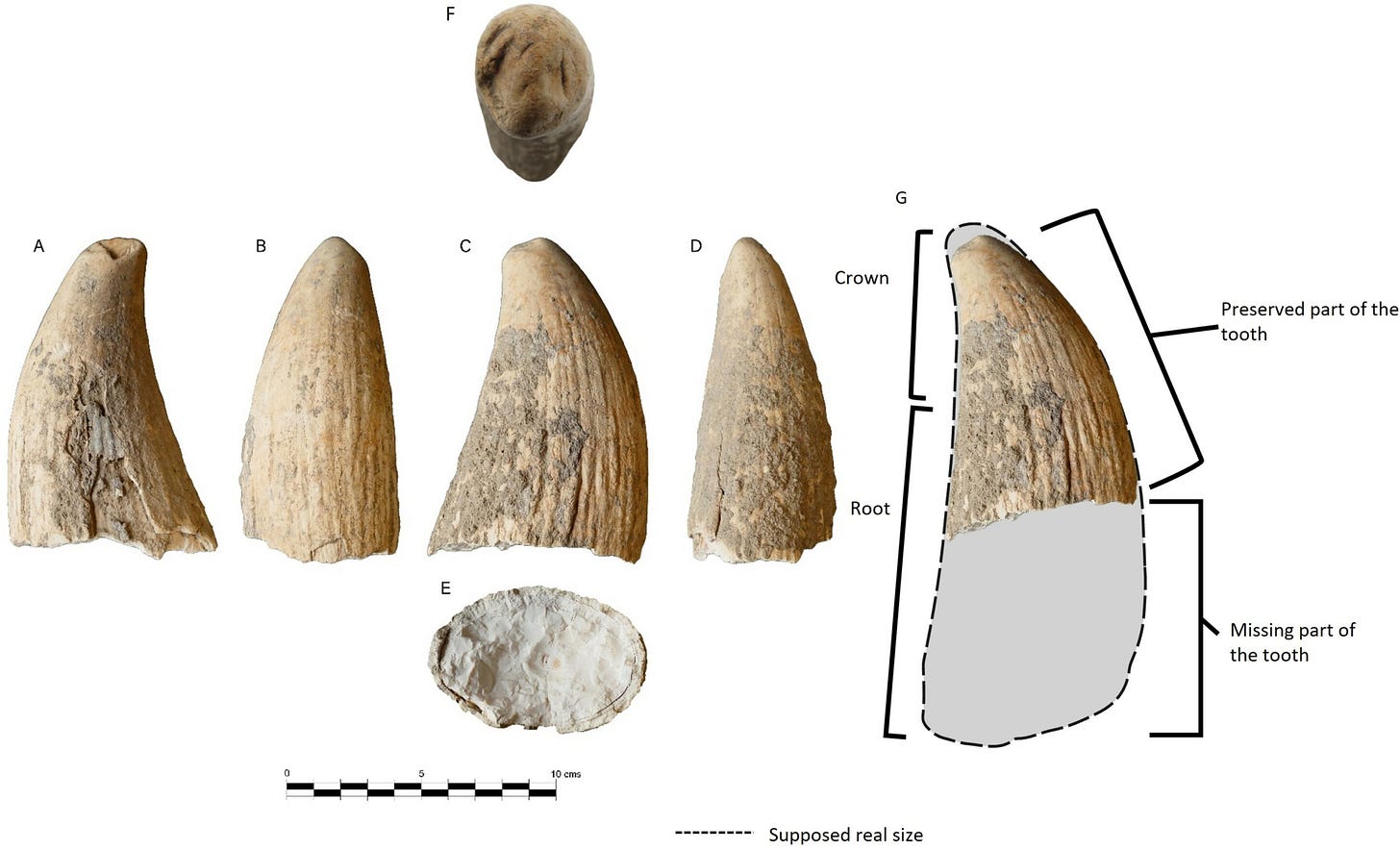

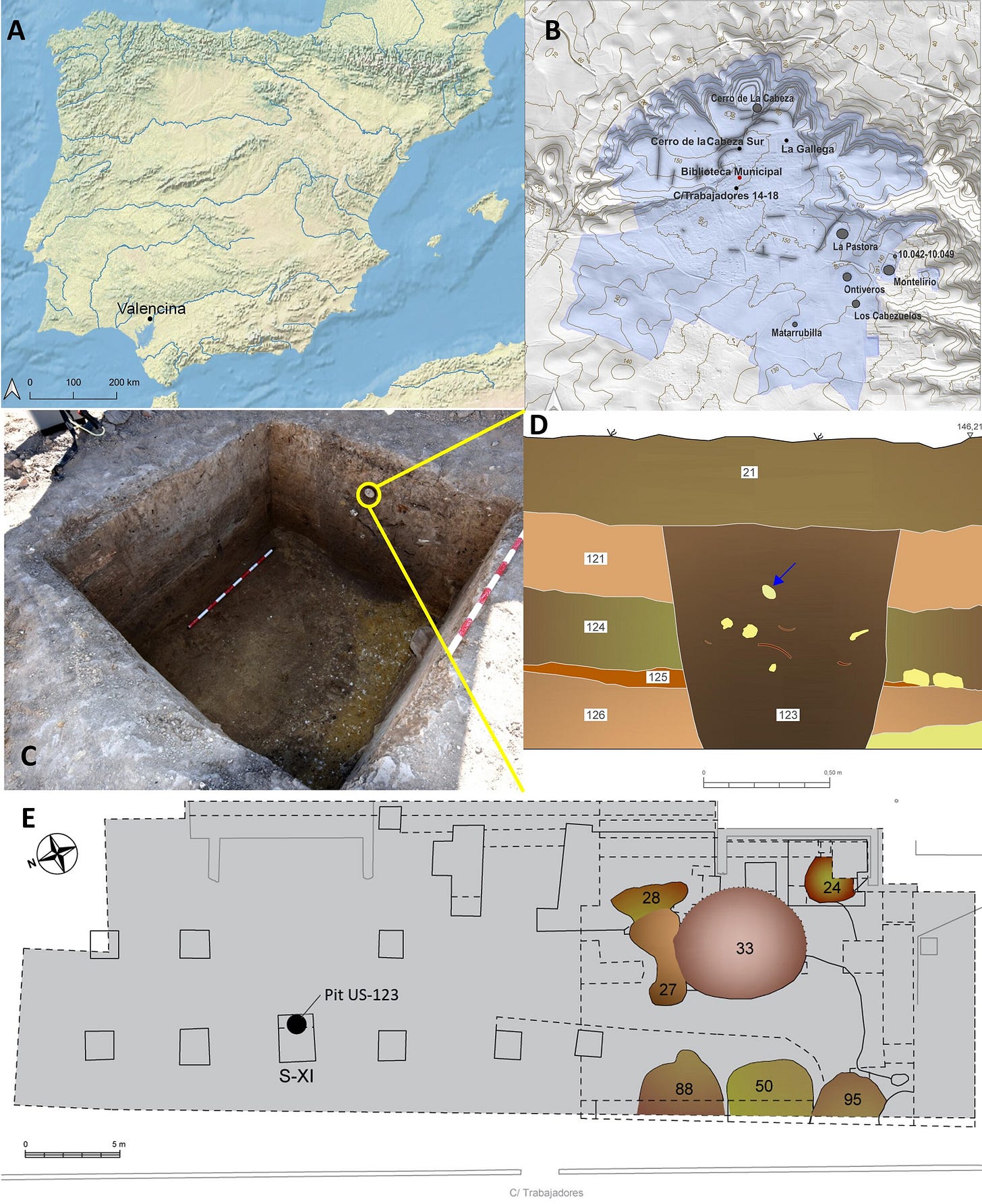

On a hilltop in southwestern Spain, far from the nearest coast, a strange relic was pulled from the soil in 2018. It wasn’t gold or finely worked flint, but something far rarer: the worn, bio-eroded tooth of a sperm whale. Measuring1 over 13 centimeters and weighing more than 400 grams, the tooth was unearthed from a conical pit at the sprawling Copper Age megasite of Valencina de la Concepción. It had been buried deliberately, among pottery sherds, grinding stones, and charred animal bones.

The object posed a puzzle. Why was a marine mammal tooth, likely scavenged from a beach, transported dozens of kilometers inland and ceremonially interred in a pit without any human remains? What meaning might it have held for the inhabitants of this ancient proto-urban settlement?

A Copper Age Megasite with Oceanic Ties

Valencina is no ordinary archaeological site. Spanning over 450 hectares near modern-day Seville, it was one of the largest and most complex Copper Age centers in Europe. The community constructed massive ditches, tholos tombs, and thousands of pits over centuries of occupation. Its residents imported ivory, cinnabar, amber, and rock crystal, indicating vast exchange networks.

But the discovery of a sperm whale tooth stands out. Not only is it the first marine mammal remain ever found at Valencina, it is also one of the earliest examples of sperm whale ivory known from European prehistory.

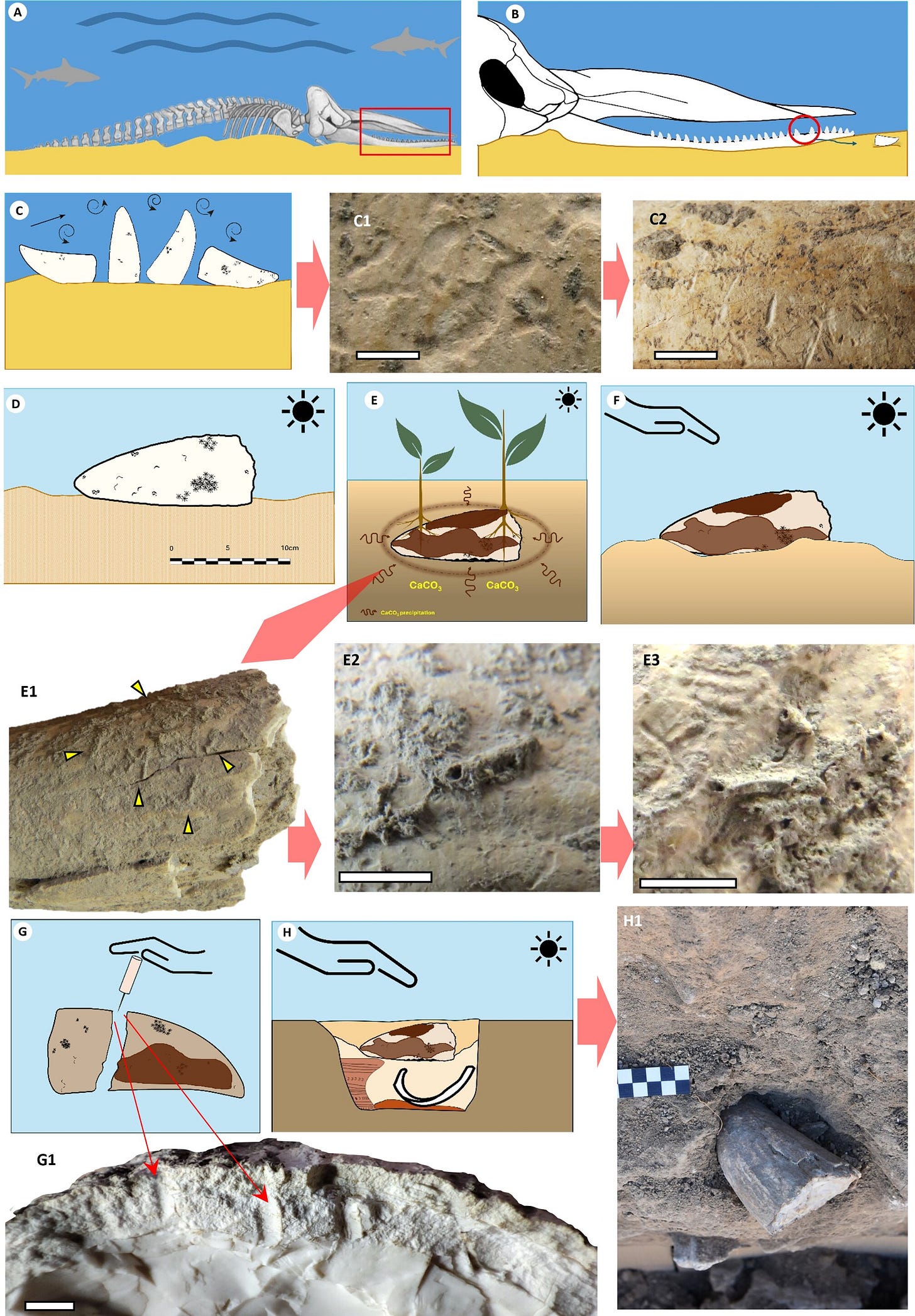

"This tooth likely spent time on the seafloor, where it became home to marine invertebrates before washing ashore," noted the authors of the recent multidisciplinary study.

Microscopic analyses revealed a suite of marine bioerosion traces—borings from sponges, annelid worms, and barnacles—as well as shark bite marks. These clues suggest that the whale died at sea, its carcass sank, and the tooth remained submerged long enough to accrue biological scars. Only later did it resurface, likely after a storm event, and get picked up by humans.

Human Hands and Symbolic Significance

Once collected, the tooth was worked. Researchers identified a series of anthropogenic cut marks, tool incisions, and breakage patterns, indicating an attempt to segment the tooth—possibly to harvest pieces for ornamentation or other symbolic artifacts. Yet no such objects have been recovered from the pit or other parts of the site.

Instead, the tooth was deposited whole, perhaps after a failed attempt to modify it, in a context that suggests a ritual act. The pit in which it was found lacked human remains, but contained carefully selected items: two ceramic sherds with drilled holes, an unusual concentration even at a site famous for pottery. Many of the bones had been burned, and some bore fresh fractures.

"These objects were likely deposited together in a single event, not as waste but as a structured offering," the study concluded.

This interpretation draws from widespread Neolithic and Copper Age practices across Europe, where valuable or symbolically charged items were placed in pits or ditches as non-funerary votive deposits.

The Sea in the Mind of Inland Communities

Valencina's inhabitants were not coastal fishers, but the sea nonetheless appears to have loomed large in their imagination. The sperm whale tooth joins a growing list of marine-derived materials found at the site: scallop shells, sandstone slabs bearing fossil traces, and perhaps most famously, ostrich eggshells and elephant ivory sourced from North Africa.

The sea, then, may have represented more than a distant ecological zone—it was part of a cosmological worldview that linked rare and powerful animals with social identity, status, and ritual performance.

"The deliberate burial of this tooth, an object from the deep sea and possibly from a massive creature never seen alive by the community, suggests it held totemic or ancestral significance," said the team.

A Wider Mediterranean Context

Only one other sperm whale tooth of similar age and context is known in Europe—from the sanctuary of Monte d’Accoddi in Sardinia. Like the Valencina specimen, it was also found in a monumental, non-domestic setting and bore evidence of human modification.

These rare finds hint at a wider Copper Age Mediterranean tradition in which beached whale ivory was transformed into sacred or socially meaningful objects. They also underscore how prehistoric societies along the Iberian Peninsula participated in long-range networks of symbolic and material exchange.

Conclusion

What emerges from this unusual discovery is a complex portrait of human-sea relationships in deep time. Far from being landlocked farmers disconnected from the ocean, the people of Valencina embedded marine objects into their rituals and, by extension, into their cultural memory.

The sperm whale tooth, moved from seafloor to shore, from artifact to offering, stands as a fossilized echo of that entanglement.

Related Research

Melis, M. G., & Zedda, M. (2021). Sperm whales in the Neolithic Mediterranean: A tooth from the sanctuary of Monte d'Accoddi (Sardinia, Italy). Antiquity, 95. https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2021.96

Schuhmacher, T., Banerjee, A., Dindorf, W., Sastri, C., & Sauvage, T. (2013). The use of sperm whale ivory in Chalcolithic Portugal. Trabajos de Prehistoria, 70, 185–203. https://doi.org/10.3989/tp.2013.12109

Lefebvre, A., Marín-Arroyo, A. B., & Álvarez-Fernández, E. et al. (2021). Interconnected Magdalenian societies as revealed by the circulation of whale bone artefacts in the Pyreneo-Cantabrian region. Quaternary Science Reviews, 251, 106692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106692

García Sanjuán, L., Scarre, C., & Wheatley, D. W. (2017). The mega-site of Valencina de la Concepción (Seville, Spain): debating settlement form, monumentality and aggregation in southern Iberian Copper Age societies. Journal of World Prehistory, 30(3), 239–257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10963-017-9107-6

Ramírez-Cruzado Aguilar-Galindo, S., Luciañez-Triviño, M., Muñiz Guinea, F., Cáceres Puro, L. M., Toscano Grande, A., Díaz-Guardamino, M., Vargas Jiménez, J. M., Schuhmacher, T. X., Martínez Sánchez, R. M., Guillamón Dávila, S., Rodríguez Vidal, J., & García Sanjuán, L. (2025). From the jaws of the “Leviathan”: A sperm whale tooth from the Valencina Copper Age Megasite. PloS One, 20(5), e0323773. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0323773