In the tangled rainforests of the Yucatán Peninsula, traces of a civilization long thought to be rural and scattered are now being reimagined as highly structured and densely populated. New research published in Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports by Francisco Estrada-Belli, Marcello Canuto, Ivan Šprajc, and Juan Carlos Fernandez-Diaz upends conventional narratives about the Classic Maya. The study uses a vast new dataset of lidar (light detection and ranging) imagery to suggest that as many as 16 million people may have lived in the Central Maya Lowlands during the Late Classic period, between 600 and 900 CE.

This population estimate represents a 45% increase over earlier numbers and is remarkable not only for its scale, but for where it is concentrated. The study suggests that the northern Maya Lowlands—once thought to be sparsely populated farmland dotted with ceremonial centers—may have been just as urbanized, if not more, than the southern regions historically associated with major sites like Tikal.

“Our analysis of lidar data from both the northern and southern Central Maya Lowlands indicates that the Late Classic period population in the northern region was significantly larger than previously recognized,” the authors write.

Lidar as Time Machine

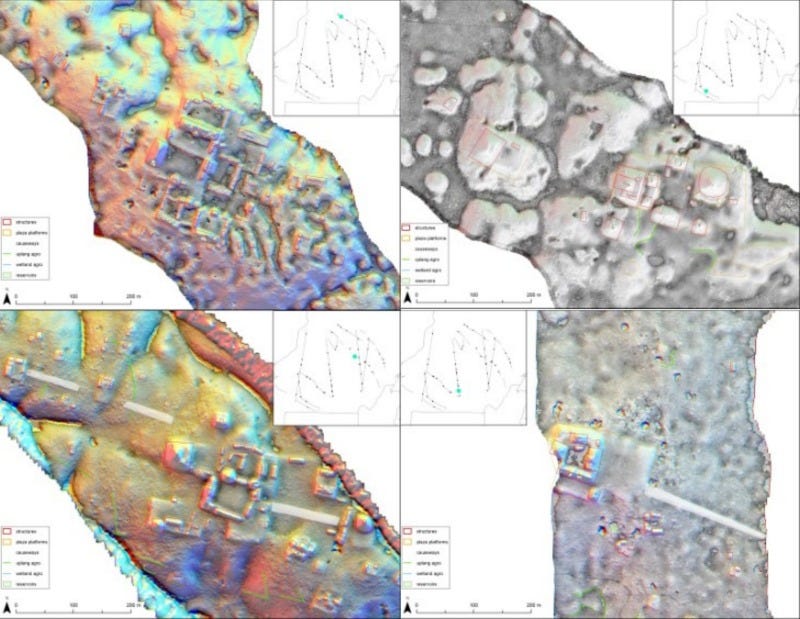

The study relies on 853 square kilometers of reprocessed and integrated lidar data collected from various public and private sources, including environmental scans conducted by NASA’s Goddard Lidar, Hyperspectral and Thermal Imager (G-LiHT). This is no small leap in methodology. Traditional archaeological methods have long been hindered by the sheer density of jungle vegetation, limiting researchers to pedestrian surveys and targeted excavations. Lidar, however, can see through the canopy, revealing subtle changes in topography that indicate buildings, roads, terraces, and agricultural fields.

And what it found was not a scattered mosaic of huts and temples. The landscape is structured around elite-controlled plaza groups, forming civic-ceremonial centers across both densely and sparsely populated areas. Nearly all residential structures identified in the study were within five kilometers of one of these plaza groups—suggesting a level of regional planning and integration that has more in common with low-density cities than isolated homesteads.

“These findings challenge the notion of isolated rural Maya households,” the authors argue. “Even in sparsely settled areas, households were spatially integrated into a broader network of elite nodes.”

The Myth of the Rural North

Until now, most large-scale population studies in the Maya region focused on southern Guatemala’s Peten region, with lidar studies centered around known sites such as Tikal, Holmul, and La Corona. These earlier datasets had estimated average population densities at around 80 to 120 people per square kilometer. But in the new study, which samples both northern and southern regions, the northern dataset shows dramatically higher densities—ranging from 154 to 260 people per square kilometer.

“The northern half of the Central Maya Lowlands was consistently more densely occupied than its southern counterpart,” the researchers write, “despite lidar transects avoiding known large urban centers like Calakmul and Dzibanché.”

Even when researchers restricted their estimates to upland areas—excluding wetlands that were likely uninhabitable—the figures remained robust: 180 to 305 people per square kilometer, consistent across both north and south.

A Uniform Model of Maya Urbanism

One of the study’s most striking conclusions is the identification of a consistent pattern of urban-rural integration across the entire 95,000-square-kilometer area studied. The data show a uniform spatial model: residences and agricultural features radiating out from ceremonial and administrative centers. These centers formed a multi-tiered network, suggesting governance and exchange were managed in both urban and rural zones.

“Markets and elite administrative nodes were fundamental elements of Maya urbanism,” the study notes. “This model extends beyond cities and into rural areas, implying that no community was truly isolated.”

Even the placement of agricultural infrastructure—stone walls, terraces, ditches—was coordinated. The study found greater investment in agriculture in the northern region, correlating with its higher population densities. These were not random farms; they were carefully engineered landscapes connected to the civic core.

Rewriting the Narrative of Collapse

This rethinking of Maya demographic and spatial structure has implications far beyond settlement numbers. It revises how archaeologists understand the complexity, resilience, and vulnerability of the Maya world. A densely networked population with overlapping layers of civic, ritual, and agricultural coordination could offer new explanations for both the success and collapse of the Classic Maya.

Such a system may have supported large populations efficiently, but it may also have introduced new stress points. The more interconnected the system, the more susceptible it might have been to political disruption, environmental strain, or resource competition.

Still, the scale of integration and planning reflected in the new lidar data is striking. In the northern forests where earlier scholars expected scattered hamlets, researchers now find the shadows of cities. A civilization once imagined as rural and decentralized now appears much more like a deeply entangled landscape of regional capitals, elite-managed farms, and civic plazas—cities without walls, forested but densely lived.

“This study suggests that ancient Maya urbanism was more widespread, more structured, and more interconnected than previously recognized,” the authors conclude.

Related Research

For those interested in broader applications of lidar and ancient urbanism, consider the following related studies:

Canuto, M. A., et al. (2018). “Ancient lowland Maya complexity as revealed by airborne laser scanning of northern Guatemala.” Science, 361(6409). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aau0137

Garrison, T. G., et al. (2019). “Lidar survey of northern Guatemala reveals interconnected centers and previously unknown sites.” Nature Communications, 10(1), 2736. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10215-y

Hutson, S. R., et al. (2021). “Low-density urbanism and agricultural intensification in the northern Maya Lowlands: new lidar data from Yucatan, Mexico.” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 62, 101265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2021.101265

Chase, A. F., & Chase, D. Z. (2020). “E Pluribus Unum: Lidar and the Maya City.” In Ancient Mesoamerica, 31(2), 247–259. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0956536120000128

Estrada-Belli, F., Canuto, M. A., Šprajc, I., & Fernandez-Diaz, J. C. (2025). New regional-scale Classic Maya population density estimates and settlement distribution models through airborne lidar scanning. Journal of Archaeological Science, Reports, 66(105288), 105288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2025.105288