For decades, the story of humanity’s first steps beyond Africa felt tidy. Around 1.8 million years ago, a single adaptable species, Homo erectus, expanded into Eurasia, carrying stone tools, long legs, and a flexible way of life. It was a narrative built on confidence and a handful of iconic fossils.

Then came Dmanisi.

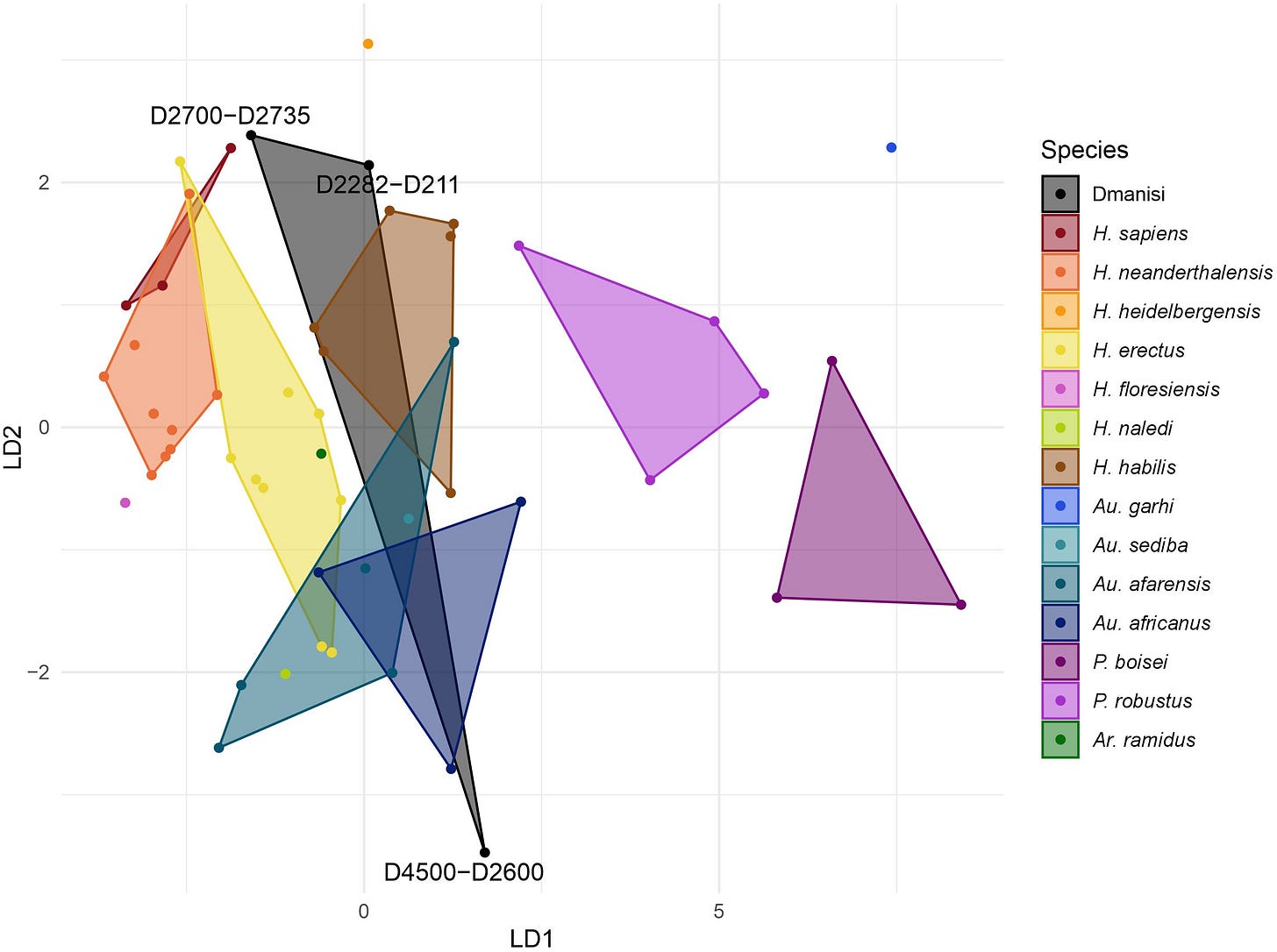

Perched in the southern Caucasus of modern-day Georgia, the Dmanisi site has yielded five remarkably complete hominin skulls, all broadly dated to the same window in deep time. They are ancient, unmistakably human, and stubbornly inconsistent. Some look small-brained and primitive. Others appear more derived, with proportions closer to later members of the genus Homo. For years, researchers have argued over whether this diversity reflects variation within one species or the presence of multiple lineages living side by side.

A new study shifts1 that debate from faces to teeth. And in doing so, it sharpens the question of who, exactly, left Africa first.