In a quiet storeroom of the University of Turin's Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography, an unnamed woman sits still. Her skin, darkened by centuries of dehydration and burial, carries faint, deliberate lines. These marks, etched some 800 years ago into the flesh of her face and wrist, whisper stories of a vanished world—and of a tattooing tradition that archaeologists are only just beginning to decipher.

The woman is part of no documented excavation. Donated anonymously in the early 20th century, she arrived with no known provenance other than a vague label: "South American." But thanks to a careful blend of non-destructive imaging, microchemical analysis, and cultural context, this anonymous ancestor is now at the center of an extraordinary finding1.

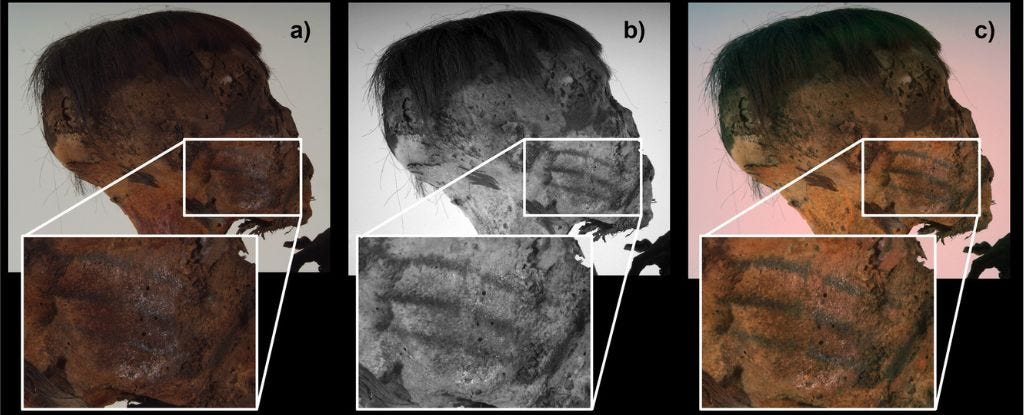

"The three detected lines of tattooing are relatively unique: in general, skin marks on the face are rare among the groups of the ancient Andean region and even rarer on the cheeks."

A Face in the Desert Wind

Radiocarbon dating of textile fibers still clinging to the body place her lifetime between 1215 and 1382 CE. Her posture—seated, knees bent—and the remaining shreds of fabric suggest a traditional Andean funerary bundle, or fardo, common among Paracas and other southern coastal Peruvian cultures.

Beneath the museum lights, the tattoos are nearly invisible. Time has tanned her skin into a sepia canvas. But with infrared reflectography and false-color imaging, researchers revealed a set of three dark lines running across her right cheek, a partial mirrored pattern on her left, and a solitary, S-shaped curve etched into her right wrist.

Facial tattoos, particularly on the cheeks, are almost never preserved or documented in South American mummies. "It has to be highlighted that, as far as cultural classification on the basis of skin markings is concerned, the findings from the Turin mummy are unique," the authors write.

These minimalist motifs contrast with the elaborate avian or geometric designs typically found on hands, forearms, or legs in other Andean mummies. No known parallels have been found in skin, pottery, or textiles—though some resemblance to decorative S-patterns in coastal Peruvian cloth remains speculative.

What Lies Beneath the Ink

The ink itself tells an equally curious story.

While most ancient tattoos are assumed to have been drawn using carbon-based pigments like soot or charcoal, this mummy breaks that mold. Chemical and microscopic analysis revealed something else entirely: a blend of magnetite and iron-rich silicate minerals, possibly augite. These compounds are not only rare in tattooing contexts but suggest a level of intentionality and access to specific geological materials.

"The results highlight the presence of magnetite, a commonly used material both in present and past cultures, as well as other iron-rich phases of the pyroxene silicates group... with a small amount of carbon-based materials, possibly not intentionally added."

The mineral composition points to a pigment mixture that absorbed infrared light, hence its detectability through imaging—but differed fundamentally from soot. Magnetite is magnetic and metallic, commonly used in ritual contexts. Its pairing with pyroxene silicates, also found in the highland and coastal regions of Peru, raises intriguing questions about the symbolic meaning and sourcing of tattooing materials.

An Inked Enigma

Without a burial context or known cultural affiliation, the mummy's story remains fragmentary. Yet her tattoos offer a powerful glimpse into the diversity of body modification practices across the ancient Andes.

Face markings may have held communicative or symbolic value, visible to others during life—perhaps reflecting status, kinship, ritual roles, or protective magic. The wrist tattoo, meanwhile, aligns with broader Andean traditions. But unlike the birds, felines, or serpents seen on other bodies, her symbols are abstract and restrained.

Chemical analysis also challenges the assumption that ancient ink was homogeneously plant-based or simple. This find suggests regional variability in pigment recipes and possibly in tattooing tools or techniques. If magnetite was used deliberately, its rarity in other mummy analyses may reflect gaps in research rather than actual absence.

The Value of Forgotten Bodies

Museum specimens lacking excavation records often fall into the shadows of archaeological inquiry. But this study shows how thoughtful science and context-aware interpretation can breathe meaning into unprovenienced remains. Through light and mineral, through pigment and pattern, one silent woman speaks again.

"This multidisciplinary work broadens the vision of ancient tattoo practice and highlights the importance of performing compositional analyses on tattoo pigments."

Related Research

Pabst, M.A., et al. (2010). Different staining substances were used in decorative and therapeutic tattoos in a 1000-year-old Peruvian mummy. Journal of Archaeological Science, 37(8), 3256–3262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2010.07.026

Vásquez Sánchez, V.F., et al. (2013). Estudio Microquímico Mediante MEB–EDS del pigmento utilizado en el tatuaje de la Señora de Cao. Archaeobios, 7(1), 5–21. Link

Maita Agurto, P.K., & Minaya Cabello, E. (2013). El uso de reflectografía infrarroja en el registro de tatuajes en momias Paracas-Necrópolis. Arqueología y Sociedad, 26, 117–130. https://doi.org/10.15381/arqueolsoc.2013n26.e12391

Friedman, R., et al. (2018). Natural mummies from predynastic Egypt reveal the world's earliest figural tattoos. Journal of Archaeological Science, 92, 116–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2018.02.002

Mangiapane, G., Di Francia, E., Gerst, R., Radelet, T., Aceto, M., Agostino, A., & Boano, R. (2025). Rare tattoos shape and composition on a South American mummy. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 73, 561–570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2025.04.013