In the heart of ancient China’s political machinery, where emperors ruled from Chang’an and armies marched from loess plains, a quieter but no less crucial revolution was taking place in the soil. Beneath the feet of palace courtiers and farmers alike, changes in agricultural practice were unfolding that would sustain one of the most enduring empires in Chinese history: the Han Dynasty.

Recent research1 led by Jingwen Liao and colleagues from Leiden University and Fudan University used stable isotope analysis to trace the long-term evolution of farming strategies in the Guanzhong Basin—a region that not only served as the Han capital's granary, but also as a climate archive written in millet.

Digging into the Tombs of Farmers

The research team analyzed carbon (δ13C) and nitrogen (δ15N) isotope ratios in common millet (Panicum miliaceum) and foxtail millet (Setaria italica) recovered from five archaeological sites: four Han Dynasty tombs and one Late Neolithic site. In the Han tombs, pottery granaries buried with the dead still contained husks of the grains that fed the living.

This gave the researchers a rare chance to compare Neolithic and Han-era millet agriculture directly. The isotopic values in these crops serve as chemical fingerprints of the conditions in which they were grown, including water availability and soil fertility.

"Compared to the Late Neolithic period, the δ15N values of common and foxtail millets in the Han capital and its surrounding areas increased by 6.5‰ and 2.7‰ respectively, indicating an intensification of fertilization strategies," the authors report.

Farming in a Changing Climate

The Han Dynasty unfolded during a time of environmental transition. Monsoon rainfall was gradually decreasing, and winters were cooling. Archaeological soils in the Guanzhong Basin show a shift toward drier conditions after about 3000 years ago. Yet isotope values indicate that Han farmers were adapting. Their fields were not becoming less productive.

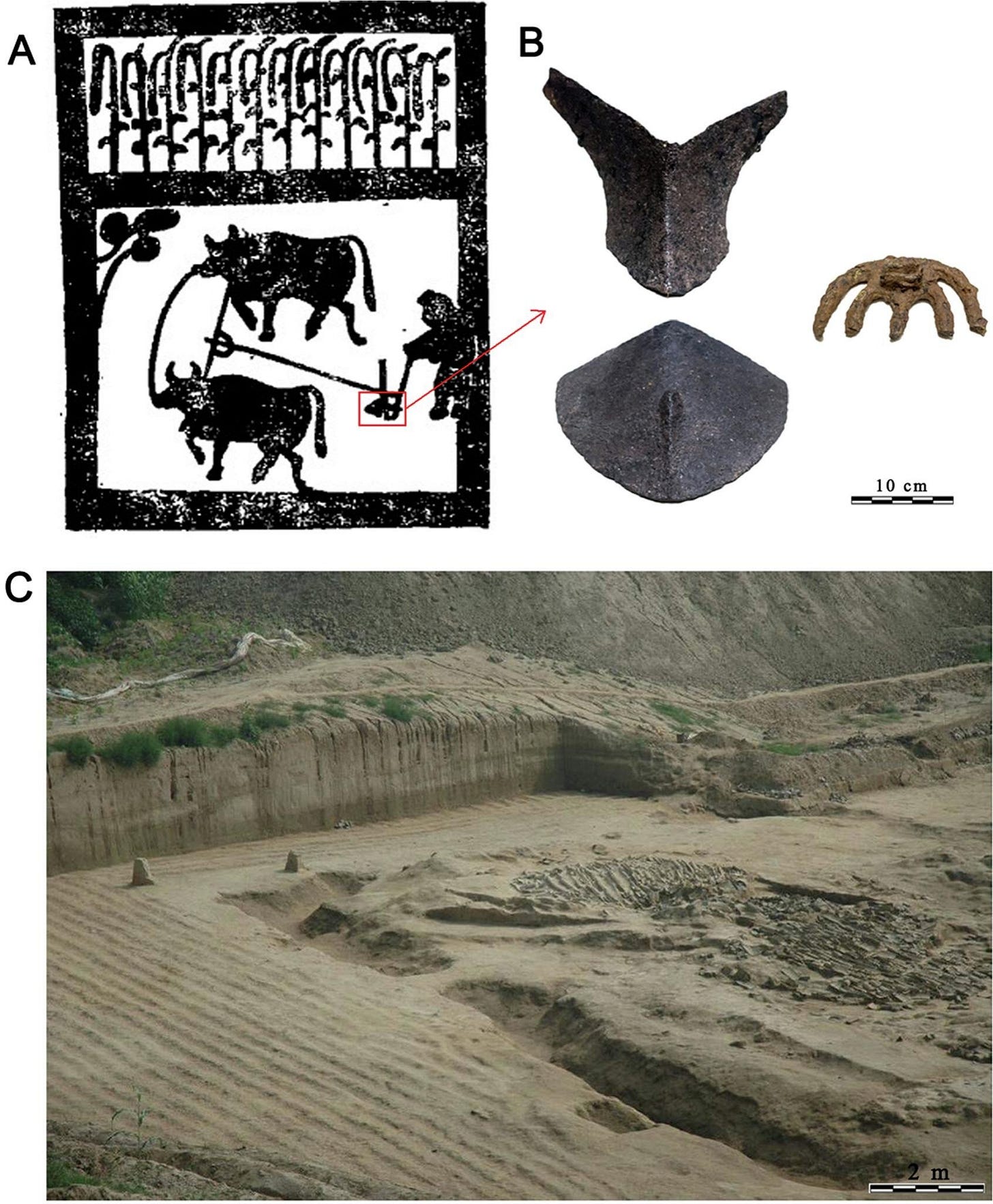

The drop in δ13C values during the Han period suggests increased water input during millet cultivation. This aligns with historical accounts of extensive canal systems like the Longshou and Lingzhi Canals, engineered to keep farmland irrigated despite shifting rainfall.

Pig Pens and Privies: Ancient Composting Systems

One innovation that stands out is the fusion of household waste streams into usable fertilizer. Historical texts and tomb models indicate that latrines and pigsties were often built side by side. Waste from both humans and animals was collected in compost pits and then applied to fields. The Han manual Fan Shengzhi Shu even recommended manure from pig pens as especially valuable.

"The purpose of such structures was to mix pig manure, human manure, and feed scrap to obtain well-decomposed manure with higher organic content," note the authors.

Animal husbandry expanded during the Han, with household pig-raising becoming widespread. That meant more accessible fertilizer for smallholder farmers, who could also supplement it with plant ash, silkworm waste, and even river mud.

Farmers, Elites, and the Political Economy of Soil

The tombs studied likely belonged to landlords or minor aristocrats, whose wealth derived from the land and the labor that worked it. Because agriculture was taxed in-kind, elites had strong incentives to maximize yields. Better tools, crop rotation, and organized irrigation were part of a systemic push toward intensive farming.

What this study makes clear is that intensification wasn’t simply a response to climate stress or technological availability. It was also tied to the political structure of the empire—a system that demanded surplus and stability, and therefore innovation in how land was managed.

"The success of intensive irrigation and fertilization strategies in the Han Dynasty not only fostered advances in farmland management practices but also helped elites accumulate more wealth," the study concludes. "This may have accelerated social divisions and unequal economies within the empire."

Isotopes and the Memory of Soil

The nitrogen isotope signature of millet provides a kind of soil memory, revealing how deeply fertilization was embedded in Han agriculture. Unlike historical texts, which emphasize ideals, isotope data capture everyday practice. The study documents a shift from modest manuring in the Neolithic to intensive fertilization in the Han era.

In this way, ancient crops become not just remnants of past meals, but archives of human ingenuity. They show how agricultural knowledge was transmitted, adapted, and institutionalized across centuries.

A Broader Agricultural Legacy

The researchers argue that the Guanzhong Basin should be seen as more than just a political center. It was a laboratory of early imperial agronomy. Stable isotope analysis, especially when combined with historical records and archaeological data, opens a path to reconstructing ancient land use with precision.

Yet the story is incomplete. Millet is a C4 crop, which responds differently to water conditions than wheat or rice. Expanding isotopic studies to C3 plants will be essential to better understand how water management varied across the empire. For now, millet offers the clearest window into how one of the world’s great early empires fed itself—and how its people responded, with persistence and invention, to the challenges of climate and rule.

Further Reading and Related Research

Christensen, B. T., Jensen, J. L., Dong, Y., Bogaard, A. (2022). Manure for millet: Grain δ15N values as indicators of prehistoric cropping intensity of Panicum miliaceum and Setaria italica. Journal of Archaeological Science, 139, 105554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2022.105554

Kanstrup, M., Holst, M. K., Jensen, P. M., Thomsen, I. K., Christensen, B. T. (2014). Searching for long-term trends in prehistoric manuring practice: δ15N analyses of charred cereal grains from the 4th to the 1st millennium BC. Journal of Archaeological Science, 51, 115–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2013.04.018

Allen, E., Yu, Y., Yang, X., et al. (2022). Multidisciplinary lines of evidence reveal East/Northeast Asian origins of agriculturalist/pastoralist residents at a Han dynasty military outpost in ancient Xinjiang. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 10, 932004. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2022.932004

Ma, M., Dong, J., Yang, Y., et al. (2023). Isotopic evidence reveals the gradual intensification of millet agriculture in Neolithic western Loess Plateau. Fundamental Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fmre.2023.06.007

Liao, J., Allen, E., Henry, A. G., Laffoon, J. E., Li, M., Liu, D., & Sheng, P. (2025). Millet stable isotopes reveal the advance of agricultural practices in the core political regions of early imperial China. Catena, 257(109148), 109148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2025.109148