The Bone Archive of Human History

If genes are blueprints, skulls are blueprints weathered by time. Across millennia, Europe’s crania have silently recorded the toll of famine, climate, warfare, and migration. A new study1 by Pavel Grasgruber of Masaryk University traces the sweeping changes in male cranial morphology from the Upper Paleolithic to the cusp of the Bronze Age, offering a rare skeletal counterpoint to the genetic narratives that often dominate prehistoric discourse.

Using data from over 3,900 male skulls across 103 prehistoric populations, Grasgruber’s statistical analysis compares 22 craniometric traits—11 absolute measurements and 11 shape indices—to track shifts in size and form over 30,000 years. The results hint at a Europe in flux: a continent repeatedly reshaped not just by migration but by the slow churn of diet, disease, and cultural transformation.

Broad Faces, Tall Vaults: The Paleolithic Legacy

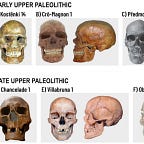

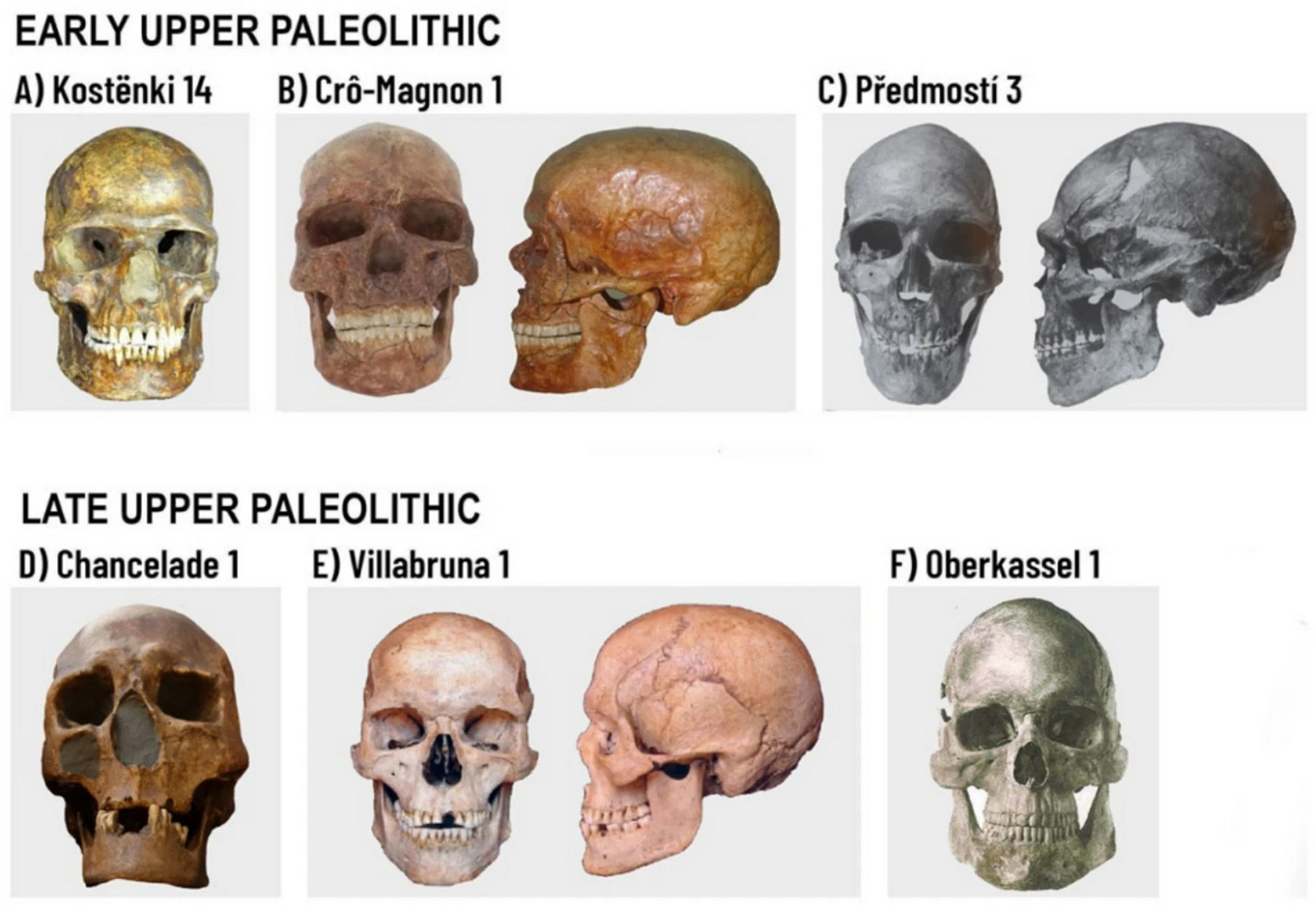

During the Upper Paleolithic, the typical European skull was long, robust, and broad-faced. This was not a monolith but a collection of morphotypes—from the famously rugged Crô-Magnon to the more harmonious Brno forms seen in Czech Gravettian burials.

"The Crô-Magnon morphology appears older... it can be recognized on the Aurignacian skulls from Mladeč, whereas the Brno morphology is first documented with the Gravettian," Grasgruber notes.

Late Upper Paleolithic skulls were slightly smaller, likely reflecting colder climates and nutritional stress. Yet many features persisted: pronounced faces, tall cranial vaults, and striking variation between Western (Magdalenian) and Eastern (Epigravettian) groups.

Mesolithic Adaptation: Taller Skulls, Gracile Features

With the onset of the Holocene, Mesolithic populations across Europe began exhibiting taller, narrower skulls. The changes were subtle but consistent: reduced facial breadth, narrower noses, and greater cranial height.

These shifts seem to coincide with changes in mobility, subsistence, and possibly body size.

"East European Mesolithic groups remained tall and robust, while Western groups showed signs of gracilization," according to the comparative results.

Farmers from Anatolia: A New Cranial Type

One of the most dramatic shifts came with the arrival of Neolithic farmers from Anatolia around 6000 BCE. These migrants brought with them a distinct morphology: narrow, high faces; smaller skulls; and gracile features distinct from the indigenous hunter-gatherers they encountered.

"Their small crania accord with their small body height, not much exceeding 160 cm," the study reports.

These newcomers likely displaced or assimilated local populations. By 4000 BCE, the robust skulls of Europe's Mesolithic past were largely confined to peripheries like Scandinavia and the Russian forest zone.

A Clash of Forms: The Steppe Arrivals

Around 3000 BCE, Europe saw another demographic and morphological upheaval. Pastoralists from the Pontic-Caspian steppe arrived, descendants of the Jamnaja (Yamnaya) culture. Their influence was profound, both genetically and skeletally.

Corded Ware populations emerging from this horizon were ultradolichocephalic—extraordinarily long-skulled with high foreheads. Bell Beaker populations, by contrast, were short-skulled and wide-faced, possibly due to founder effects and regional admixture.

"The Corded Ware crania were a completely new, unique phenomenon... not a simple average of founding populations."

"Bell Beaker skulls were completely antagonistic to Corded Ware forms, reflecting extreme cranial roundness and reduced facial projection."

Genetics vs. Skeletal Reality

While paleogenomics has rewritten many narratives of European prehistory, Grasgruber's study underscores that genes alone cannot explain the physical diversity of ancient populations.

The Bell Beaker and Únětice cultures, for example, share nearly identical autosomal profiles but differ dramatically in skull shape. This suggests rapid morphological shifts due to male-driven founder events and local ecological adaptation.

A Record of Continual Change

Today, modern European skulls look little like their Paleolithic predecessors. The short, high, gracile cranial forms common in recent centuries may owe more to changes in nutrition, lifestyle, and climate than to deep ancestry. Yet the ancient record, preserved in bone, reminds us that the human face has always been a product of history—a moving target shaped by who we are, what we eat, and where we go.

Related Research

Olalde, I., et al. (2018). The Beaker phenomenon and the genomic transformation of northwest Europe. Nature, 555, 190–196. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25738

Lazaridis, I., et al. (2024). A paleogenomic history of southeastern Europe. Nature, 622, 310–320. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07252-0

Allentoft, M. E., et al. (2024). Population genomics of Stone Age Eurasia. Nature, 615, 213–223. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06506-6

Von Cramon-Taubadel, N., & Pinhasi, R. (2011). Craniometric data support a mosaic model of demic and cultural Neolithic diffusion. PNAS, 108(22), 9350–9355. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1013136108

Grasgruber, P. (2025). The evolution of European cranial morphology: From the Upper Paleolithic to the Late Eneolithic steppe invasions. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 17(5). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-025-02207-5