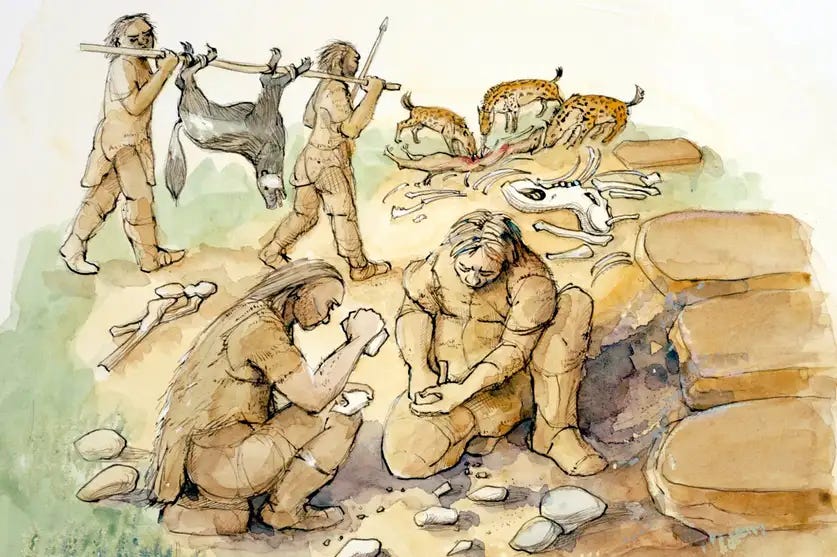

There are few things as quintessentially human as the act of teaching. Whether around a campfire, in a workshop, or beside a burial cairn, transmitting knowledge has been central to how societies grow, persist, and adapt. A recent study by Ivan Colagè and Francesco d’Errico takes a sweeping look at this process, offering what may be the most comprehensive timeline yet of cultural transmission in the human lineage.

Spanning more than three million years and 103 cultural traits, their analysis, published in PLOS ONE1, seeks not just to catalog the artifacts of early humans but to trace how knowledge of these tools and practices was passed on. The research reframes ancient stone tools, pigments, beads, and even burial customs not merely as products of ingenuity but as echoes of a long lineage of teaching, learning, and increasingly complex social organization.

"Culture cannot exist without ways to acquire information from others," the authors argue, reminding us that behind every flake of obsidian or ochre-stained shell lies an exchange between generations.

From Hammers to Harpoons: Charting the Timeline of Cultural Traits

Colagè and d’Errico's team assembled a dataset of over 100 cultural traits, each tied to its first consistent appearance in the archaeological record—from rudimentary stone hammers 3.3 million years ago to painted burials just before the Holocene. Their aim wasn’t simply to track innovations but to reverse-engineer how those innovations might have been taught.

Each trait was evaluated across three dimensions of transmission:

Spatial: Was learning done through distant observation or guided, hands-on instruction?

Temporal: Did the knowledge require a single lesson or a sequence of modular training episodes?

Social: Was the information passed from parent to child, across peer groups, or broadly within communities?

Surprisingly, patterns emerged. For example, as technologies became more complex, so too did the methods required to transmit them. Traits that appeared after 600,000 years ago—such as hafted tools or pigment processing—often involved intentional guidance, structured repetition, and even what the authors call "explanation in absence of action," a precursor to verbal teaching.

"The results identify trends in the evolution of cultural transmission and reveal a coevolutionary dynamic between the emergence of novel cultural traits and the complexification of transmission strategies," the authors write.

Teaching Without Talking? Language and the Ghosts of Gesture

One of the study’s boldest claims is that forms of teaching resembling verbal instruction existed well before the appearance of spoken language. Around 600,000 years ago, early humans were likely using sophisticated gestures, perhaps paired with proto-language, to explain how to make and use tools.

By 200,000 to 100,000 years ago—the estimated dawn of fully modern language—the archaeological record shows a leap in the complexity of behaviors, from structured burials to the use of symbolic ornaments. These behaviors demand not just physical dexterity but abstract thinking, planning, and crucially, explanation.

"Acquiring the necessary knowledge to perform a task implies learning several disconnected pieces of knowledge the utility of which will only become apparent at a future stage," they note.

A Ratchet for Culture

Anthropologists often speak of the "ratchet effect"—the idea that cultural knowledge can build upon itself, generation after generation, in a way that no single individual could replicate alone. This study adds empirical depth to that metaphor, showing how modes of transmission had to evolve alongside the artifacts they preserved.

Teaching by gesture molding, opportunity provisioning, or evaluative feedback doesn’t require words. But once articulate language emerges, a whole new world of teaching becomes possible—including the ability to transmit ideas removed from immediate action.

This, the researchers suggest, marks a tipping point: culture no longer rides on imitation alone, but on instruction, imagination, and increasingly abstract modes of communication. In short, teaching becomes not just a way to learn, but a way to think.

Teaching as Legacy, Not Just Learning

Beyond the evolutionary arc, this research reshapes our understanding of early human societies. Teaching wasn’t an optional behavior; it was infrastructural. Communities that developed better strategies for passing down knowledge had a selective advantage. Cultural success became linked not only to the tool in hand, but to the ability to ensure that others could use it, remake it, and improve it.

"Even individual learning often operates within a more complex social learning environment," the authors conclude, highlighting the scaffolding required to sustain innovation over millennia.

In a time when machines can learn but struggle to teach, this study is a timely reminder: what made us human was not just the ability to adapt, but the capacity to share how.

Suggested Additional Readings

Sterelny, K. (2012). The Evolved Apprentice: How Evolution Made Humans Unique. MIT Press. https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262018872

Stout, D., Hecht, E. E., Khreisheh, N., Bradley, B., & Chaminade, T. (2015). Cognitive demands of Lower Paleolithic toolmaking. PLOS ONE, 10(4), e0121804. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0121804

Morgan, T. J. H., Uomini, N. T., Rendell, L. E., Chouinard-Thuly, L., Street, S. E., Lewis, H. M., ... & Laland, K. N. (2015). Experimental evidence for the co-evolution of hominin tool-making teaching and language. Nature Communications, 6, 6029. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7029

Shipton, C. (2020). A noisy signal: The evolution of teaching, learning, and language. Evolutionary Anthropology, 29(6), 287–299. https://doi.org/10.1002/evan.21829

Tennie, C., Call, J., & Tomasello, M. (2009). Ratcheting up the ratchet: on the evolution of cumulative culture. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 364(1528), 2405–2415. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2009.0052

Mesoudi, A., Whiten, A., & Laland, K. N. (2006). Towards a unified science of cultural evolution. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 29(4), 329–383. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X06009083

Colagè, I., & d’Errico, F. (2025). An empirically-based scenario for the evolution of cultural transmission in the human lineage during the last 3.3 million years. PloS One, 20(6), e0325059. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0325059