Domestication as a Turning Point in Human Evolution

The domestication of plants and animals is often framed as a cornerstone of civilization. It’s the moment, we’re told, when our ancestors turned from the unpredictability of foraging to the structured stability of farming. Domestication allowed for permanent settlements, surplus food, the rise of states—and ultimately, the birth of what we call “history.”

But what if this story gets it backwards?

A growing number of archaeologists and evolutionary biologists now argue that domestication wasn’t simply something humans did to other species. Rather, it was something that happened between us—over generations, unconsciously, through evolutionary feedback loops in which both humans and other species co-evolved.

Three recent papers—two in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B1 2and one in PNAS3—bring this radical reinterpretation into sharper focus. Taken together, they shift domestication from a narrative of human conquest to one of ecological entanglement.

A New Definition: Not Domination, but Co-evolution

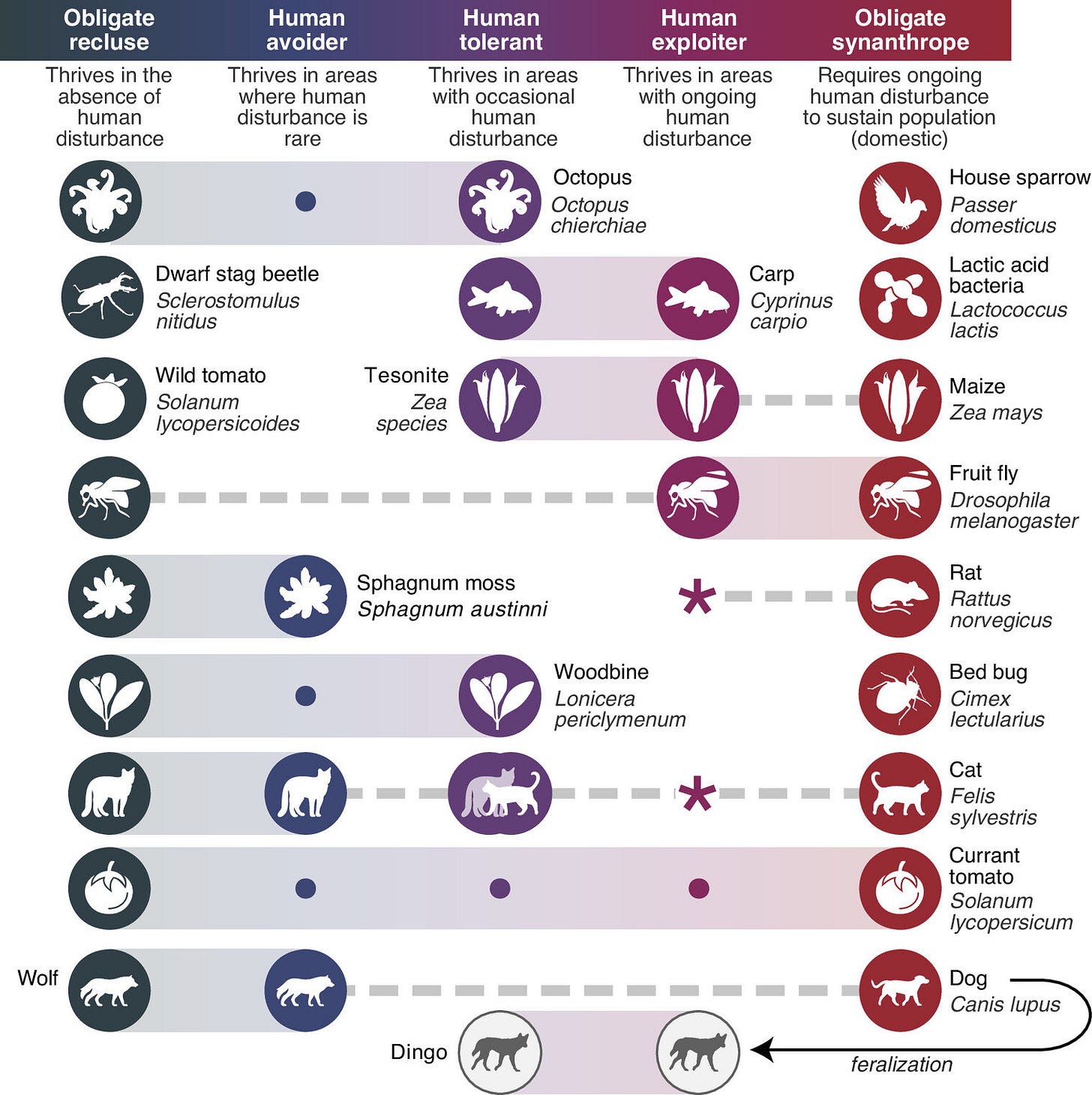

In a provocative paper published in PNAS, evolutionary biologist Kathryn A. Lord and her colleagues propose a redefinition of domestication as an evolutionary process, rather than an intentional act of human control. According to their framework, species adapt to anthropogenic niches—the ecological spaces humans unintentionally or intentionally create.

“Domestication is not just about humans taming nature,” Lord explains. “It's about how species evolve in response to the environments we create.”

This means animals like free-ranging dogs or urban pigeons—long marginalized in discussions of domestication—may be more representative of the domestication process than previously thought.

Lord’s team introduces a spectrum of domestication, from species that adapt peripherally to human environments to those that become completely dependent on us. This model accounts for both the deliberate breeding of livestock and the evolutionary drift of animals that simply learned to live with us.

Unintentional Origins: Domestication Without Design

In a second paper, archaeobotanist Robert N. Spengler and collaborators press further. Their argument, published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, contends that most domestication was unintentional.

“Domestication is the foundation of modern civilization,” says Spengler. “Understanding how it really happened—across species, regions, and millennia—reshapes our sense of what it means to be human today.”

Rather than viewing domestication as a singular invention, they propose that it unfolded gradually across generations as humans and species entered into increasingly tight co-dependencies.

The article challenges scholars to reconsider how archaeological evidence—such as grain size, seed dispersal traits, or animal morphology—is interpreted. Instead of looking for a single domestication “event,” we might better understand the process as a series of micro-adaptations.

Parallel Histories: Cereal Domestication Across Eurasia

A third study, also in Philosophical Transactions B, looks at one of the most iconic examples of domestication—grain agriculture. Rita Dal Martello and colleagues conducted a sweeping analysis of archaeological cereal grain data from across Eurasia.

They found something remarkable: the evolutionary traits we associate with domesticated cereals—such as increased grain size—emerged independently in multiple regions.

“Our findings highlight how similar evolutionary patterns emerged independently across Eurasia,” Dal Martello notes. “This suggests that domestication was not a singular event but a series of parallel processes influenced by various environmental and cultural factors.”

In other words, domestication didn't spread like a spark catching fire. It emerged repeatedly in different places under similar conditions—wherever humans and plants became entangled in each other's life cycles.

Toward a New Archaeology of Entanglement

These new frameworks compel archaeologists and anthropologists to rethink domestication not as the product of ancient genius, but as an evolutionary dialogue—an emergent outcome of long-term interaction.

As our species continues to alter the biosphere at an unprecedented scale—urbanizing ecosystems, redirecting evolution via CRISPR, and domesticating microbiomes—the stakes of understanding these deep-time relationships grow ever higher.

“The archaeological record offers essential insights into how long-term human-plant-animal relationships unfold,” says Spengler. “These lessons could inform more sustainable practices today and tomorrow.”

We didn’t just domesticate the dog or the wheat. In a sense, they domesticated us too.

Related Reading

Zeder, M. A. (2012). The domestication of animals, Philosophical Transactions B

Larson, G. et al. (2014). Current perspectives and the future of domestication studies, PNAS

Arbuckle, B., & Makarewicz, C. (2009). The origins and spread of animal domestication, Journal of Anthropological Archaeology

Spengler, R. N., Denham, T. P., & Fuller, D. Q. (2024). Seeking consensus on the domestication concept. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 379(1903), 20240188. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2024.0188

Dal Martello, R., Stevens, C. J., & Fuller, D. Q. (2024). Plant domestication as a multidimensional process: A case study from cereal grain size evolution across Eurasia. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 379(1903), 20240193. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2024.0193

Lord, K. A., Olsen, R. A., Larson, G., & Cagan, A. (2024). Rethinking the definition of domestication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 121(20), e2413207122. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2413207122