The teeth that spoke of origin

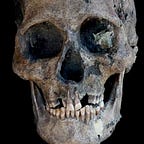

Archaeologists rarely find voices in the soil. What they find instead are bones, ornaments, and—if they are lucky—teeth. Teeth hold stories, not only of diet and health, but of the deliberate decisions people made about who they were.

A new study by Yue Zhang of the Australian National University, published in Archaeological Research in Asia (Zhang, 2025),1 explores one such story: the long, painful, and symbolic tradition of tooth ablation in ancient Vietnam. By compiling dental evidence from 276 individuals spanning the Neolithic to Iron Age, Zhang maps how this practice of pulling healthy teeth—often the front incisors—moved through space and time as people migrated, mingled, and remade their worlds.

“Intentional tooth removal is among the most intimate forms of body modification,” explains Dr. Zhang. “It required endurance, social meaning, and a shared understanding of why such pain was necessary.”

Performed without anesthetic, tooth ablation was common across early agricultural societies in Southeast Asia. It was more than decoration. In many communities, it marked maturity, kinship, or belonging. The new study suggests it also traced the fault lines of migration—an embodied map of who arrived, who adapted, and who resisted.