The Point Beneath the Hearth

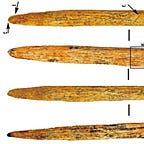

High in the North Caucasus, tucked into the limestone layers of Mezmaiskaya Cave, archaeologists have found1 what may be the oldest bone projectile point in Europe. It’s not made of flint or obsidian. It’s not large. In fact, it’s just 9 centimeters long, whittled from the dense outer layer of a bison’s limb. But its implications are enormous.

This sliver of bone, shaped, smoothed, hardened in fire, and likely hafted with tar, speaks not of crude imitation, but of invention. Dated to between 70,000 and 80,000 years ago, its maker was not Homo sapiens. It was a Neanderthal.

Reshaping the Narrative on Neanderthal Technology

The projectile point was discovered by a team led by Liubov Golovanova, who has spent decades investigating the archaeological layers of Mezmaiskaya. The tool’s presence among hearth ash, flint chips, and other Mousterian artifacts situates it squarely within a Neanderthal context—long before Homo sapiens entered the region.

“The production technology of bone-tipped hunting weapons used by Neanderthals was in the nascent level in comparison to those used and introduced by modern humans,”

— Golovanova et al., Journal of Archaeological Science

Despite this modest disclaimer, the point’s construction involved knowledge far beyond crude bone smashing. Neanderthal craftspeople selected cortical bone for its durability, scraped away muscle scars, and ground the surface into a sleek, symmetrical form. Microscopic striations show precise shaping with stone tools. Its conical tip was even thermally treated, a technique requiring controlled fire use.

This wasn’t a clumsy improvisation. It was weaponsmithing.

A Weapon Designed to Fly

The spear tip’s dimensions—too slender for thrusting—point to its use as a projectile. Unlike earlier bone tools shaped like awls or digging sticks, this one was clearly designed to travel through air.

To hold it in place, Neanderthal artisans used bitumen or resin, identified via spectroscopic analysis. This adhesive technology was already known from other Mousterian contexts, often used to haft flint points. But using it with bone, especially one engineered for aerodynamic use, adds a new dimension to our understanding of Neanderthal versatility.

A Fracture in the Tip—and the Evidence

Impact cracks near the point’s edge, examined with micro-CT imaging, closely match damage seen in experimentally used bone-tipped weapons. These suggest the spear struck something—perhaps a bison, perhaps a deer. Either way, someone tried to resharpen the tip afterward, a mark of reuse.

“To be an effective hunting weapon, the bone point does not need to have a sharply pointed distal end… but it needs to have a strong, conical tip, symmetrical outlines, and a straight profile.”

— Golovanova et al.

The artifact isn’t just evidence of tool use. It is evidence of planning, material selection, specialized manufacturing, and maintenance. This is the signature of sustained technical knowledge—transmitted and iterated across generations.

Independent Innovation, Not Borrowed Ideas

Much of what was once attributed to Homo sapiens alone—beadmaking, ochre use, hafting adhesives, and now projectile technology—has been documented at Neanderthal sites. The Mezmaiskaya point adds to this growing dossier.

Earlier scholars often assumed that Neanderthals borrowed behaviors from Homo sapiens after contact. But this artifact predates such interactions. Its existence reinforces a different view: that Neanderthals were parallel innovators, not passive imitators.

This doesn’t erase the differences between the two species. Homo sapiens eventually produced more standardized and regionally diverse projectile points, and did so with increasing complexity over time. But the Mezmaiskaya point suggests that the conceptual foundations were already in place—independently forged in the cold mountains of Ice Age Eurasia.

Fire-Hardened, Tar-Hafted, and Too Often Forgotten

Neanderthals lived in Mezmaiskaya Cave at several points over thousands of years, their activities layered in soot and flint, in bone and ash. One group sat by a hearth and shaped a bison leg into a hunting point. They understood fire well enough to harden the tip, resin well enough to haft it, and game well enough to test it.

The small crack at its tip is all that remains of that test. A clean fracture at high velocity—sharpened and reused until finally lost in the soil, waiting for another kind of hunter to find it.

Related Research

d’Errico, F., & Backwell, L. (2021). Earliest bone tools. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 5(7), 896–899. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01488-2

Villa, P., & Roebroeks, W. (2014). Neandertal demise: An archaeological analysis. PLoS ONE, 9(4), e96424. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0096424

Rots, V., et al. (2013). Evidence for Neandertal hafting from the Late Middle Paleolithic site of Inden-Altdorf, Germany. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(26), 10512–10517. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1302730110

Noiret, P., et al. (2020). Fire in the Paleolithic: Socio-cultural uses and technological aspects. Quaternary International, 541, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2019.10.003

Golovanova, L. V., Doronichev, V. B., Doronicheva, E. V., Poplevko, G. N., Cleghorn, N. E., Kulkov, A. M., Potrakhov, N. N., Bessonov, V. B., & Staroverov, N. E. (2025). On the Mousterian origin of bone-tipped hunting weapons in Europe: Evidence from Mezmaiskaya Cave, North Caucasus. Journal of Archaeological Science, 179(106223), 106223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2025.106223