Perched just 1.5 kilometers from the Pacific and 6.5 kilometers from the mouth of the Huaura River, the ancient settlement of Vichama might seem like an obvious candidate for a seafood-heavy diet. Yet new isotopic analysis1 of human remains suggests otherwise.

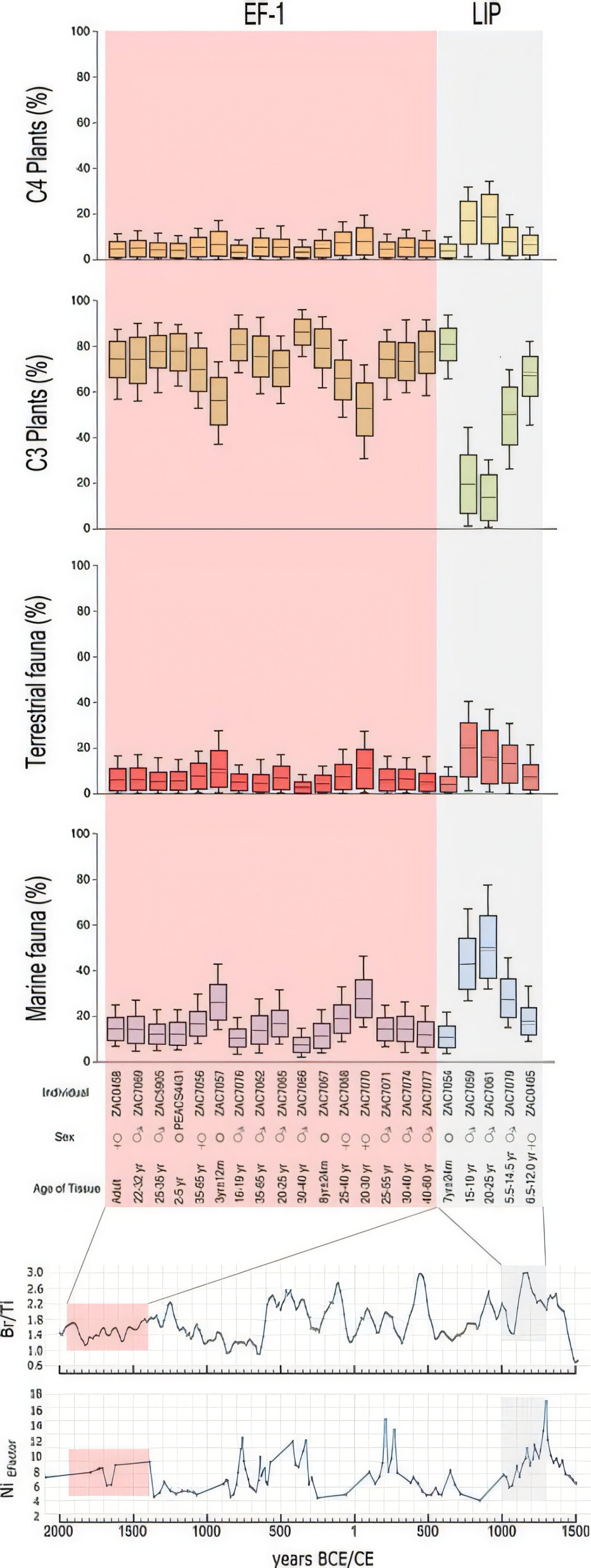

Researchers examined the bones and teeth of 38 individuals from two distinct periods: the Early Formative-1 (1800–1500 BCE), when Vichama was rising as a center of monumental architecture, and the Late Intermediate Period (1000–1300 CE), a time of shifting political landscapes and changing climate.

Stable carbon and nitrogen isotope data show that in the earlier period, residents leaned heavily on C3 plants—beans, tubers, fruits, and chilies—while marine foods made up less than a quarter of the average diet. Even C4 crops such as maize, despite being present in the region, were barely consumed.

“Theoretically, the valley is suitable for maize cultivation; however, local farmers have traditionally focused on other crops,” said lead author Luis Pezo-Lanfranco. “Maize may have been reserved for rituals rather than everyday meals.”

Climatic instability during the Early Formative may have discouraged reliance on maize, which requires consistent irrigation. Communities in broader, more fertile valleys to the north may have specialized in maize cultivation, while Vichama residents opted for resilient crops like cucurbits and tubers.

Three millennia later, isotope evidence from the Late Intermediate Period shows marine foods playing a larger role, coinciding with cooler sea surface temperatures that boosted coastal productivity. Yet farming—especially of C3 plants—remained dominant.

This dietary flexibility suggests a society attuned to environmental rhythms. Vichama’s residents intensified fishing or farming depending on prevailing conditions, without abandoning their agricultural backbone.

The research team plans to expand their study to include plant micro-remains in dental calculus, indicators of physiological stress, and pollen data to reconstruct local climate. They are also exploring the role of long-distance contacts, as artifacts from the Amazon—over 300 kilometers east—hint at possible seasonal or permanent mobility.

“We want to know why the center of regional power shifted from Caral to Vichama,” Pezo-Lanfranco noted. “The global 4.2 ka Event may have been part of the story.”

Vichama’s story is one of resilience, adaptation, and the enduring importance of farming, even in a landscape rich with marine life.

Related Research

Dillehay, T. D., et al. (2012). Early Holocene foragers and farmers in coastal Peru. Antiquity, 86(334), 762–781. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003598X00047824

Haas, J., Creamer, W., & Ruiz, A. (2004). Dating the Late Archaic occupation of the Norte Chico region in Peru. Nature, 432(7020), 1020–1023. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03146

Quilter, J., & Stocker, T. (2018). Climate and societal change in the Central Andes: Insights from archaeology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(47), 11864–11871. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1812014115

Shady, R., Haas, J., & Creamer, W. (2001). Dating Caral, a preceramic site in the Supe Valley on the central coast of Peru. Science, 292(5517), 723–726. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1059519

Pezo-Lanfranco, L., Crispin, A., Prado-Barragán, A., Abad, T., Machacuay, M., Yseki, M., Gorriti, M., Miranda, L., Apolín, J., DiMuro, A., Novoa, P., Colonese, A. C., & Shady, R. (2025). Refining dietary shifts linked to climate oscillations in the Central Andes: stable isotope evidence from Vichama (1800–1500 BCE). Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology, 4(1611071). https://doi.org/10.3389/fearc.2025.1611071