In a limestone cave on the Ligurian coast, archaeologists have uncovered something extraordinary: the earliest known example of intentional cranial modification in Europe. Buried during the last breaths of the Pleistocene, the elongated skull of an individual now known as AC12 shows1 that reshaping the human head was already part of cultural life more than 12,000 years ago.

Body modification is often treated as a modern flourish, but the archaeological record says otherwise. Long before needles inked skin or metal passed through ears, people were altering their bodies in ways that left lasting skeletal signatures. While tattoos and piercings vanish with time, bone tells a more persistent story. Among the most visually striking examples is artificial cranial modification (ACM), achieved by shaping an infant’s skull while the bones remain soft and malleable.

The Art and Method of Shaping the Skull

ACM comes in many forms, but two broad techniques dominate the archaeological record. Tabular modification involves pressing the head between rigid boards, flattening the front and back while widening the sides. Annular, or circumferential, modification uses bands of cloth or other soft materials to gently but persistently compress the skull, lengthening it into an ovoid form. Both methods must begin in infancy, when cranial bones have not yet fused, and both result in lifelong changes to the head’s profile.

The global reach of ACM is remarkable. From the Andes to the Eurasian steppe, the practice appears in contexts spanning the end of the Ice Age to recent centuries. Its meanings vary—sometimes signaling social status, sometimes marking ethnic identity, sometimes linked to beauty standards—but in all cases, it transforms the body into a visible emblem of belonging.

The Discovery at Arene Candide

The Arene Candide Cave, a large karst chamber overlooking the Mediterranean, has yielded a Late Upper Paleolithic necropolis dated to the Younger Dryas, between 12,900 and 11,600 years ago. Among at least 22 individuals interred there, AC12’s burial stands out. The cranium was set deliberately atop another individual (AC15) within a stone niche, while the mandible and other bones lay nearby in a separate cluster. Radiocarbon dating places AC12 between 12,620 and 12,190 years before present.

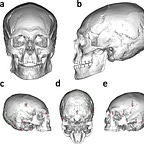

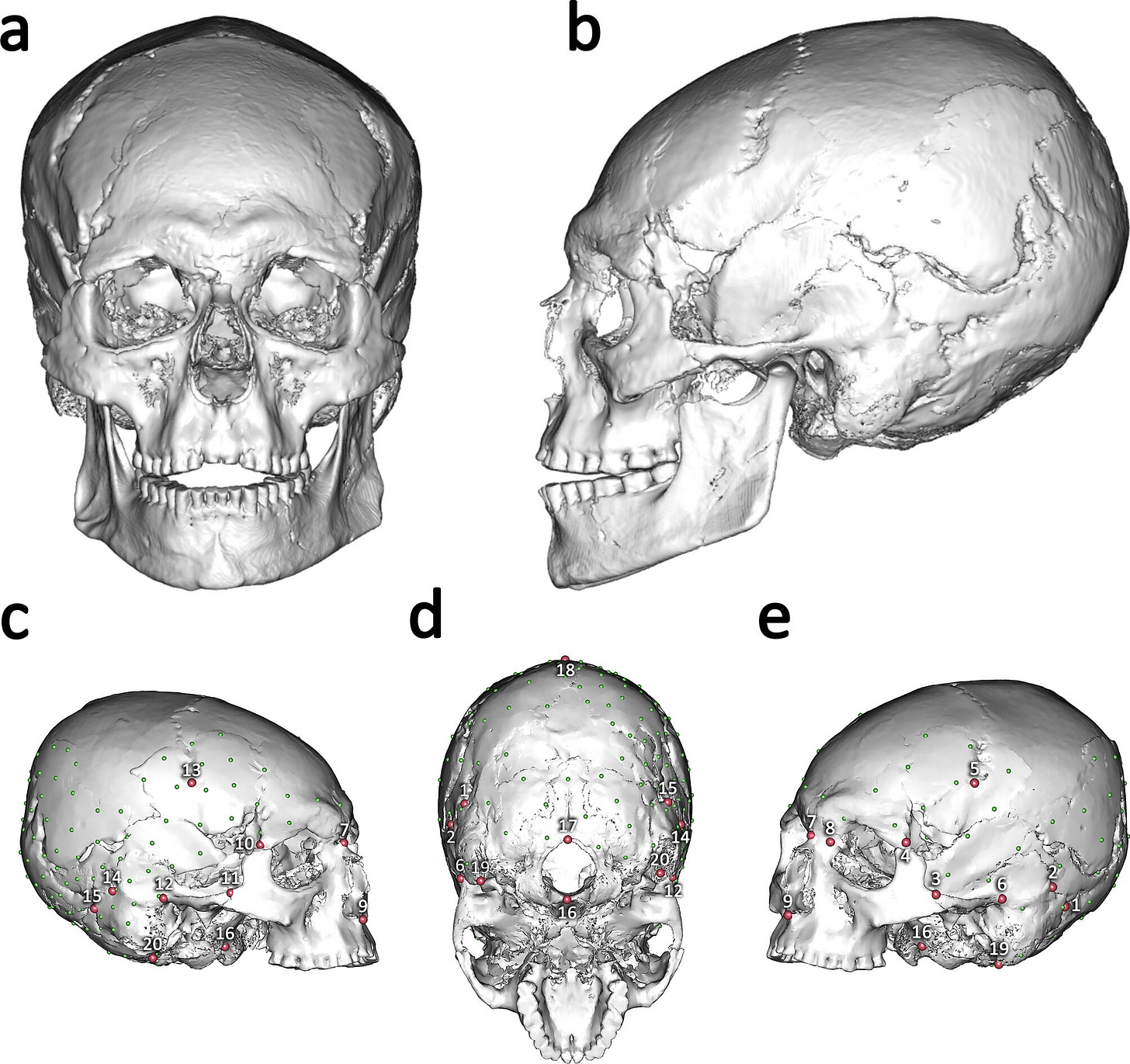

Advanced imaging was key to identifying the modification. Researchers created four separate digital reconstructions of the skull using CT scanning, manual segmentation, and 3D alignment techniques. They then compared AC12’s morphology to Late Upper Paleolithic, Mesolithic, and Neolithic Italian crania, as well as to pathological cases and a worldwide dataset of known ACM examples.

The results were clear:

“Principal component analyses place AC12 firmly within the cluster of annular-type cranial modifications,” the authors report, noting that statistical models classified the skull as intentionally modified in every case.

The elongated, flattened neurocranium does not match any known cranial pathology. Nor does it resemble the unmodified crania of other individuals from the same site.

A Cultural Marker, Not a Universal Practice

Only one of the five intact skulls from Arene Candide shows this alteration, suggesting ACM was not practiced universally within the community. Instead, it may have marked membership in a particular subgroup, family line, or social role. Because the reshaping must be done in infancy, it speaks to an identity assigned from birth, potentially tied to lineage or ceremonial function.

The burial context reinforces this interpretation. AC12 was interred as part of a carefully organized mortuary program, with deliberate placement of skeletal elements and proximity to other individuals. Such treatment suggests the modification was not incidental—it carried meaning recognized by others in the community.

Rethinking the Origins of Cranial Modification

This find pushes the practice of ACM in Europe back to the very end of the Ice Age, centuries before the agricultural transformations of the Neolithic. Its presence in a hunter-gatherer society challenges the assumption that such elaborate identity markers arose primarily in complex, sedentary communities.

Instead, the evidence points to a deeper origin, one in which body modification served as a durable way to encode belonging and transmit social identity across generations, even in highly mobile foraging groups. The head, reshaped in infancy, became a living archive of who a person was—and who they were meant to be.

Related Research

Torres-Rouff, C., & Yablonsky, L. T. (2005). Cranial vault modification as a cultural artifact: A comparison of the Eurasian steppes and the Andes. HOMO - Journal of Comparative Human Biology, 56(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchb.2004.09.003

White, C. D. (1996). Sutural effects of fronto-occipital cranial modification. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 100(3), 397–410. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199607)100:3<397::AID-AJPA4>3.0.CO;2-Q

Tiesler, V. (2014). The Bioarchaeology of Artificial Cranial Modifications: New Approaches to Head Shaping and its Meanings in Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica and Beyond. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-07440-8

Gerszten, P. C., & Gerszten, E. (1995). Intentional cranial deformation: A disappearing form of self-mutilation. Neurosurgery, 37(2), 374–382. https://doi.org/10.1227/00006123-199508000-00031

Mori, T., Sparacello, V. S., Riga, A., Ciappi, G., Ferrari, D., Seghi, F., Di Vincenzo, F., Zavattaro, M., Pasquinelli, F., Carpi, R., Peresani, M., Fontana, F., Sineo, L., Moggi-Cecchi, J., & Dori, I. (2025). Early European evidence of artificial cranial modification from the Italian Late Upper Palaeolithic Arene Candide Cave. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 27792. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13561-8