In a soggy pit on the shores of an ancient lake in what is now central Germany, a cache of wooden spears lay hidden for nearly a quarter of a million years. When they were first unearthed in the 1990s from the Schöningen site, archaeologists believed these weapons might have been crafted by Homo heidelbergensis—a hominin species ancestral to Neanderthals and perhaps to us. But thanks to a refined dating technique that analyzes1 proteins preserved in fossilized snail shells and horse teeth, the spears have lost about 100,000 years of age.

This subtle shift in chronology has profound consequences. The weapons, along with butchered horse remains and other artifacts, now appear to date to around 200,000 years ago. That’s squarely within the Middle Paleolithic and within the evolutionary range of Neanderthals—not some proto-human cousin, but the real thing.

And that makes the Schöningen spears more than just some of the oldest preserved wooden weapons in the world. It casts them as evidence of a species capable of cooperation, planning, and precision.

“Rather than a few individuals taking on dangerous animals, they’re coming together in larger groups and pooling the risk,” said Olaf Jöris of the Leibniz Center for Archaeology.

A Timeline in the Mud

The challenge with dating early Paleolithic sites lies in the lack of organic material amenable to radiocarbon methods. Those techniques top out around 60,000 years. Schöningen, however, offered another opportunity. Researchers measured the rate of racemization—how amino acids in mollusk shells and horse molars switch between molecular forms—allowing for a chemical clock to date the sediments.

That clock pointed to 200,000 years ago, not 300,000 as previously estimated. It’s a modest revision numerically, but one with dramatic implications.

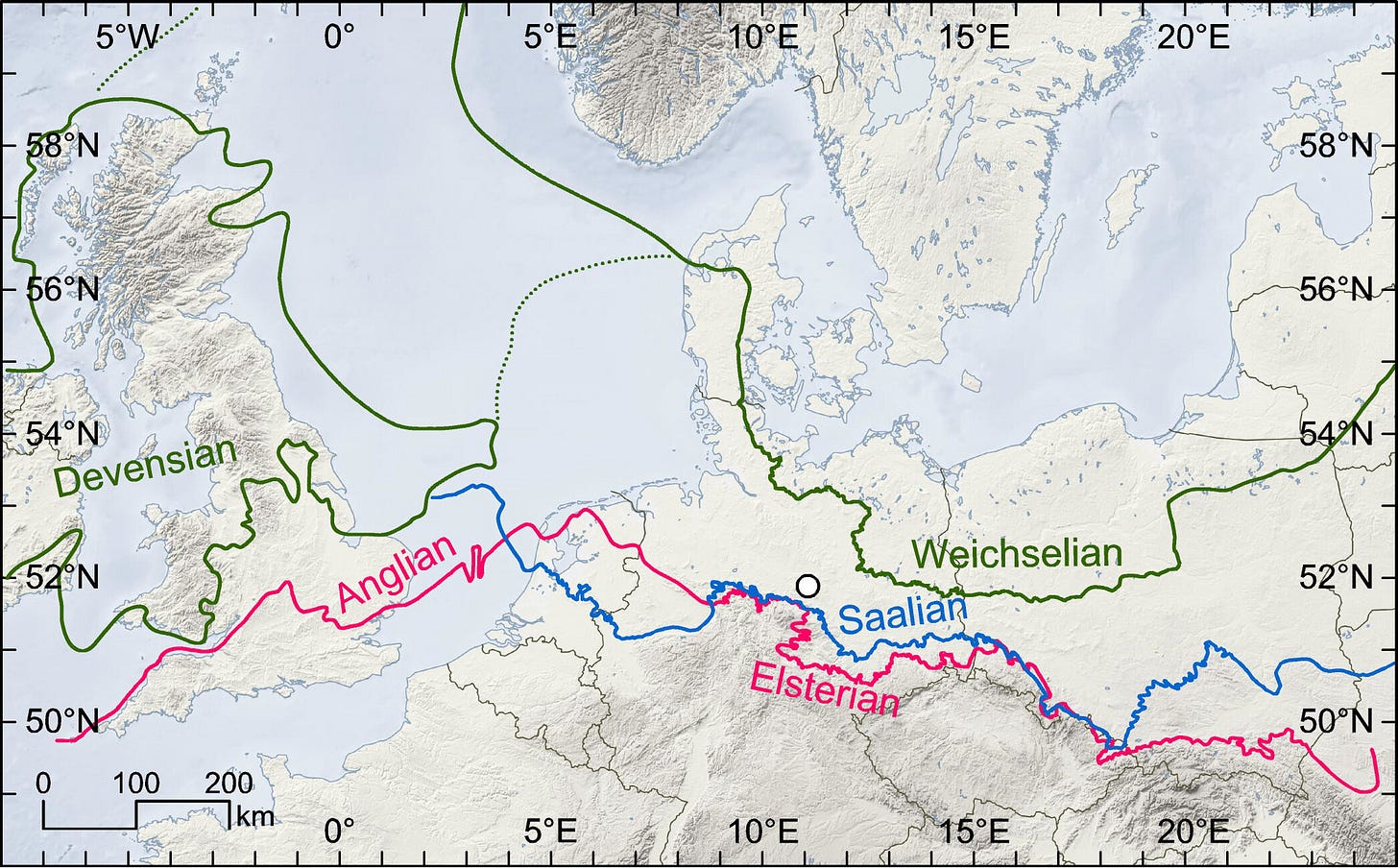

The reassignment situates the spears in a period where Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) had firmly established themselves across much of Europe. Their skeletal remains, beginning around this time, show increasing lifespans, suggesting rising survival rates and, by extension, changes in behavior, sociality, or both.

“Something is changing in how they organize and cooperate,” said Jöris. “And hunting is central to that.”

A Scene from the Middle Paleolithic

Imagine the scene: A shallow lake, thick with reeds. A herd of wild horses moves along its banks. A group of Neanderthals, each armed with a carefully carved wooden spear, works in silent coordination. Their objective is not simply to bring down a horse, but to manipulate the entire herd—to drive them toward a kill zone, perhaps a natural bottleneck or the muddy shallows where escape is harder.

This wasn’t a random ambush. It was strategy.

At Schöningen, archaeologists uncovered more than 50 horse remains, many of them juveniles and adults from the same species. That demographic profile resembles what’s seen in mass kills—targeted slaughters where hunters select and isolate prey in vulnerable clusters. The team found not only spears, but also double-pointed sticks and stone cutting tools—evidence of butchery, not just scavenging.

And the spears themselves are remarkable. Carefully worked from spruce and pine, they are balanced like modern javelins and exhibit signs of deliberate shaping at both ends.

“The craftsmanship reflects a deep understanding of wood as a material,” said Jarod Hutson, a zooarchaeologist and lead author on the study.

The tools, combined with the site’s layout and faunal remains, suggest not just individuals with weapons, but groups with roles, timing, and goals. Cooperation wasn't optional—it was essential.

What It Means for Human Evolution

If Neanderthals organized coordinated horse hunts 200,000 years ago, then key elements of human social behavior—planning, communication, and perhaps even symbolic thinking—may not be exclusive to Homo sapiens. They could stretch deeper into our shared past.

We often frame Neanderthals as rugged, clever cousins—capable of fire, stone tools, and perhaps the occasional symbolic act—but distinct from ourselves in social or cognitive nuance. The Schöningen site softens that boundary. These weren’t brutish loners lobbing sticks. They were teams of hunters leveraging collective action to maximize return and minimize risk.

“This puts them on par with early Homo sapiens in terms of social coordination,” said Hutson.

It also calls into question the neat divisions we’ve drawn between species and behaviors. Was Homo heidelbergensis truly so different from early Neanderthals? Was cooperative hunting a one-off innovation, or a broader trait among late Middle Pleistocene hominins?

For now, what Schöningen offers is a window—a small, murky one—into a scene of remarkable clarity: Neanderthals, working together, not merely to survive, but to thrive.

Additional Related Research

Here are a few studies that provide broader context for cooperative behavior and hunting among Neanderthals:

Gaudzinski-Windheuser, S., et al. (2018). Evidence for close-range hunting by last interglacial Neanderthals. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2(7), 1087–1092. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0586-2

Roebroeks, W., & Villa, P. (2011). On the earliest evidence for habitual use of fire in Europe. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(13), 5209–5214. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1018116108

Stout, D., et al. (2015). Cognitive demands of Lower Paleolithic toolmaking. Nature, 508, 503–506. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13264

Jarod M. Hutson et al.,Revised age for Schöningen hunting spears indicates intensification of Neanderthal cooperative behavior around 200,000 years ago.Sci. Adv.11,eadv0752(2025).DOI:10.1126/sciadv.adv0752