A Cave in the Highlands with Secrets from the Sea

High in Papua New Guinea’s southern highlands, Walufeni Cave holds a record that rewrites what we thought we knew about prehistoric Oceania. Beneath layers of sediment and stone tools, archaeologists uncovered something unexpected: shells from the ocean, carried over 200 kilometers inland more than 3,000 years ago.

This discovery pushes the boundaries of what scholars have long assumed about ancient Papuan societies. Far from being insular, these communities were participants in expansive networks of movement, trade, and cultural exchange stretching across seas and mountains.

“The appearance of marine shells at Walufeni marks a significant shift in the way the site was used and understood,” notes the research team in Australian Archaeology1. “These shells speak of relationships that extended far beyond the horizon.”

What 3,200-Year-Old Shells Tell Us About Social Worlds

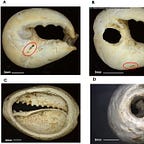

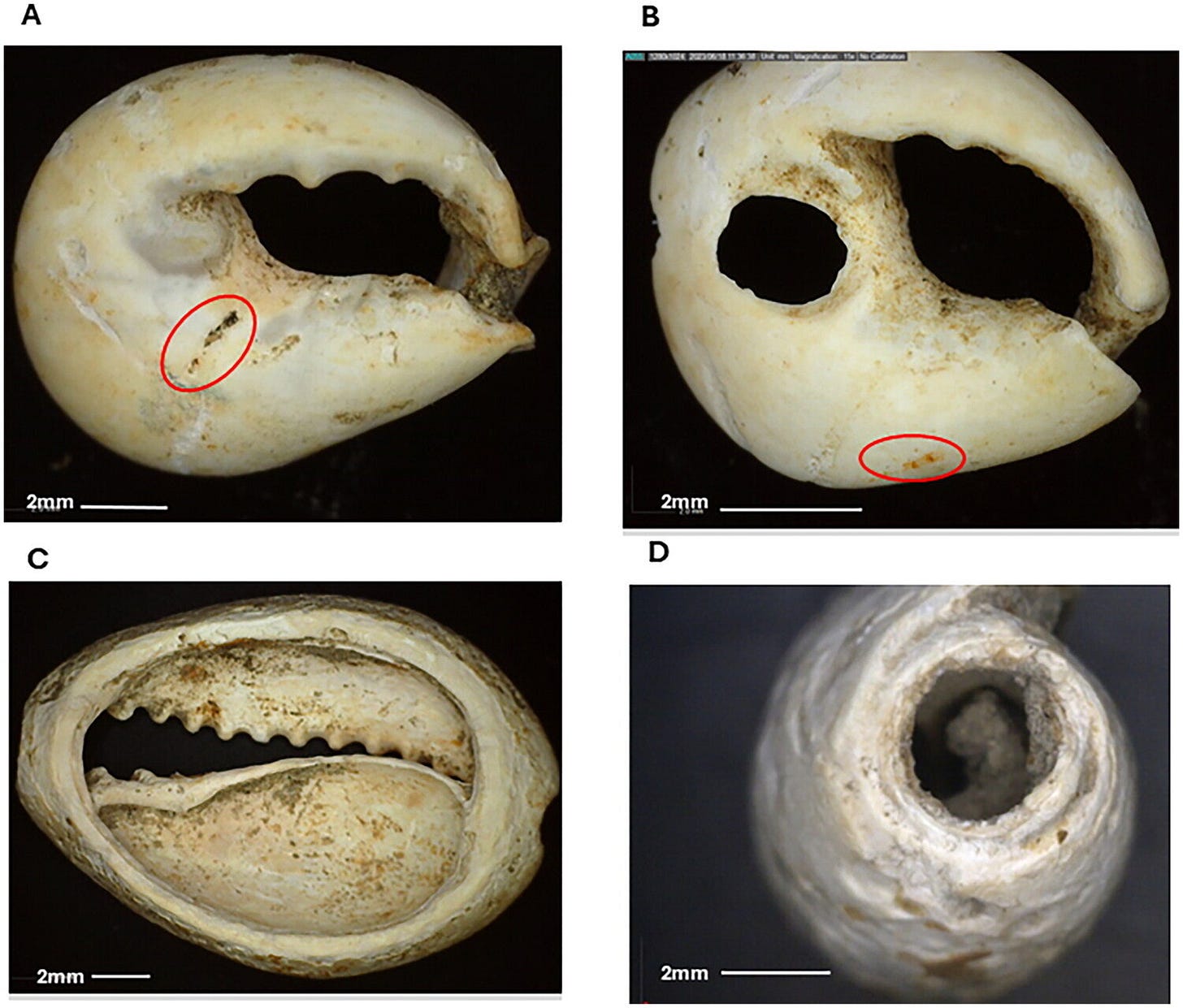

The shells found at Walufeni—dog whelks, cowries, olive shells—were not just decorative curiosities. They were cultural artifacts, modified for stitching onto garments or threading into strings. Each shell, once pried from the Gulf of Papua or Torres Strait, tells a story of hands that passed it along, of obligations, ceremonies, and exchanges that bound distant groups together.

Marine shells in Papua New Guinea were never just ornaments. They served as markers of status, currency in negotiations, and tokens in marriage alliances. For some, they were ritual objects, stitched into the fabric of ceremonial regalia. Their presence in a highland cave underscores that long before colonial charts mapped Oceania, Indigenous navigators had already traced its contours in routes of trade and kinship.

“Gastropod shells continue to be used by plateau societies today,” the authors write. “They are still sewn onto ceremonial costumes or offered in strings as exchange goods.”

A Plateau That Was Never Isolated

The Walufeni shells were deposited during the Late Holocene, a time when Lapita voyagers were crisscrossing the Pacific, carrying pottery, plants, and people into Remote Oceania. But the highlands of New Guinea, often imagined as cut off from these maritime worlds, now emerge as connected spaces.

Pottery tells a parallel story. Lapita ceramics, first introduced to New Guinea’s southern coast about 3,300 years ago, spread their technological influence inland and across the Torres Strait. Sherds from Torres Strait and northern Australia show techniques derived from these early Austronesian potters.

And the movement of objects was matched by the movement of ideas. Oral traditions from the plateau mention Sido or Souw, a cultural hero whose stories also circulate in the Torres Strait and coastal New Guinea. These myths, like the shells, map a network of shared identities across vast distances.

Why Shells Matter

To archaeologists, these shells matter because they dismantle lingering Eurocentric narratives. For too long, the highlands were cast as cultural backwaters, isolated and unchanging. Walufeni proves otherwise. These communities were active players in a regional system of interaction that spanned the Coral Sea.

This fits with what Monash University archaeologist Ian McNiven calls the “Coral Sea Cultural Interaction Sphere”—a network of trade and communication linking the Papuan Plateau, Torres Strait, and Cape York Peninsula.

Continuity and Change

The threads of this exchange extend into the present. Gastropod shells still feature in ceremonial life. Strings of shells still move between families as tokens of obligation and alliance. They are more than objects; they are social contracts, their meanings polished over centuries like the shells themselves.

Why This Changes the Narrative

Walufeni Cave reminds us that landscapes are not boundaries but bridges, and that highland societies were not passive recipients of external influence but dynamic participants in shaping Oceania’s cultural mosaic.

“These findings build on a reevaluation of Indigenous capabilities,” the study concludes, “challenging outdated notions of stasis and isolation.”

Related Research for Further Reading

McNiven, I. J., & Feldman, R. (2003). Ritual orchestration of seascapes: Maritime exchange, canoe journeys, and social networks in Torres Strait. World Archaeology, 35(3), 329–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/0043824042000185758

Summerhayes, G. R. (2000). Lapita Interaction. Terra Australis 15. Canberra: ANU Press. https://doi.org/10.22459/LI.2000

Specht, J., & Torrence, R. (2007). Lapita antecedents and successors: Archaeological change in the Bismarck Archipelago. Archaeology in Oceania, 42(S1), 6–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1834-4453.2007.tb00009.x

Barker, B., Lamb, L., Beni, T., Leavesley, M., Manne, T., & Aubert, M. (2025). Marine shell from Walufeni Cave and the origins of the Kasua: Implications for Late Holocene socio-cultural interaction on the Great Papuan Plateau, Papua New Guinea. Australian Archaeology, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/03122417.2025.2540136