In the high valleys of the Andes, more than half a millennium ago, parents shaped their children’s heads to echo the mountains that loomed over their world. This was not an eccentric flourish. It was a practice deeply entangled with identity, status, and the spiritual geography of Andean life.

Anthropologist Matthew Velasco has spent years studying these traditions of cranial modification among the Collaguas and Cavanas, neighboring peoples of the Colca Valley between A.D. 1100 and 1450. Their customs, he argues, were about more than marking ethnic boundaries. They were a way to make personhood visible—an embodied statement that tied human bodies to the sacred topography that sustained them.

The Ancient Art of Reshaping Heads

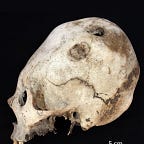

The practice of cranial deformation is as old as history itself, documented on every inhabited continent. Its origins trace back to early Homo sapiens in Late Pleistocene Australia around 13,000 years ago, and some researchers suggest even earlier experiments among Neanderthal groups. By binding an infant’s soft skull with cloth or boards, parents could elongate or flatten the head into deliberate forms—round, conical, or sloping.

In the Andes, this art reached an expressive peak. Velasco’s recent book1, The Mountain Embodied, explores how the Collaguas favored tall, elongated skulls, while the Cavanas molded theirs wide and flattened. These shapes were not arbitrary. They mirrored the silhouettes of mountains considered ancestral and divine.

A 16th-century Spanish chronicler observed that the Collaguas “wore tall, brimless hats called chucos” and sculpted their children’s heads to honor Collaguata, the distant volcano revered as their place of origin. The Cavanas, in turn, shaped skulls in homage to Gualcagualca, the snow-clad peak looming over their lands.

To understand why this mattered, Velasco suggests we consider Andean ideas of personhood. In these societies, mountains were not passive backdrops. They were animate beings, vital participants in social and ritual life. Shaping a child’s head like a mountain was not only a marker of identity—it was a way of aligning the human body with the sacred order of the cosmos.

Beyond Ethnic Labels

Older interpretations framed head-shaping as a form of ethnic branding, akin to a badge of group membership. Velasco challenges this reductionist view.

“Colonial narratives treated head shape as a mere ethnic marker,” he notes. “But the practice carried deeper meanings about social belonging and the moral fabric of life.”

That moral fabric, Velasco argues, included a vision of personhood as something constructed, not simply innate. A person could become more than a biological individual; through rituals, adornments, and bodily modifications, they could be remade into a social being recognized by both humans and sacred forces.

Privilege Written in Bone

In a 2018 study2, Velasco examined over 200 skulls from Collagua cemeteries. His analysis suggests that cranial modification was not just symbolic. It carried material consequences. Women and girls with modified skulls appear to have had access to better diets and lower exposure to violence compared to their unmodified counterparts.

“Cranial modification may have structured opportunities,” Velasco writes, “affecting who could claim land, livestock, or alliances.”

The deliberate reshaping of infant heads, then, became a tool of social differentiation—a way to inscribe hierarchy into the very bones of the next generation.

The Inca and the Spanish Intervene

By the 15th century, the Inca Empire absorbed the Colca Valley into its dominion. The Incas tolerated local head-shaping practices but did not adopt them widely. A century later, Spanish colonial authorities moved to stamp out the tradition. In 1573, Viceroy Francisco de Toledo issued an edict banning cranial modification, and the Third Council of Lima reiterated the prohibition a decade later. The reasons were steeped in colonial anxiety: bodily forms too visibly defied European norms of beauty and order.

Did It Harm the Brain?

One enduring question is whether these modifications carried neurological costs. Modern clinical research on cranial orthosis—a therapy for correcting head shape in infants—suggests otherwise.

“There’s no evidence that cranial modification caused cognitive impairment,” Velasco says. “The brain is remarkably adaptable, maintaining its volume and function even as the skull changes shape.”

This adaptability reminds us that the human body has always been a canvas for cultural ideals, whether through head-binding in the Andes or helmet therapy in pediatric clinics today.

A Legacy in Bone

Cranial modification ended in the Andes under colonial rule, but its legacy persists—in skeletal collections, in the cultural memories of Andean communities, and in debates about how bodies become social beings. Velasco frames these practices as a window into a world where mountains were kin, and identity was sculpted, literally, into the contours of the human head.

Related Research and Further Reading

Velasco, M. C. (2018). Ethnogenesis and social difference in the Andean Late Intermediate Period (AD 1100–1450): A bioarchaeological study of cranial modification in the Colca Valley, Peru. Current Anthropology, 59(1), 98–106.

https://doi.org/10.1086/695986Pitts, M. & Roberts, C. (2020). A History of the Human Head: The Evolution of the Skull and Its Cultural Transformations. Oxford University Press.

Tiesler, V. (2014). The Bioarchaeology of Artificial Cranial Modifications: New Approaches to Head Shaping and Its Meanings in Pre-Columbian Mesoamerica and Beyond. Springer.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-07440-4Blom, D. E. (2005). Embodying borders: Human body modification and diversity in Tiwanaku society. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 24(1), 1–24.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2004.07.001

Velasco, M. C. (2025). The mountain embodied: Head shaping and personhood in the ancient Andes. University of Texas Press.

Velasco, Matthew C. (2018). Ethnogenesis and social difference in the Andean late intermediate period (AD 1100–1450): A bioarchaeological study of cranial modification in the colca valley, Peru. Current Anthropology, 59(1), 98–106. https://doi.org/10.1086/695986