The Temptation of the Far South

Few frontiers on Earth have stirred the human imagination like the Southern Ocean. It is a world of furious winds, towering waves, and relentless cold—a vast, heaving belt of gray water girdling Antarctica. South of the 50th parallel, the planet bares its extremes: islands without trees, sunlight in short supply, and beaches littered with the bones of seals and seabirds. To survive here would mean mastering both the sea and the elements.

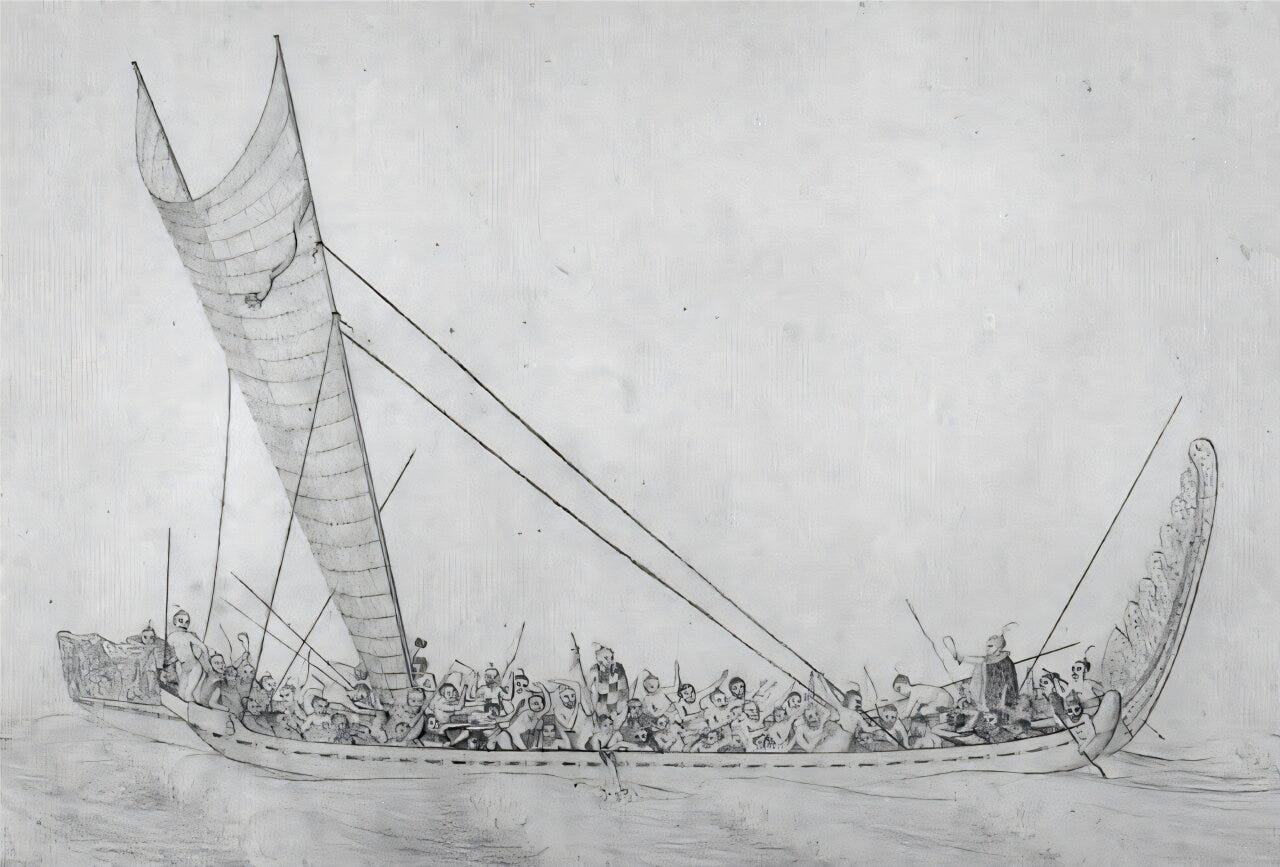

For centuries, scholars and storytellers have wondered whether anyone ever tried. Were there ancient voyagers who dared to cross that invisible line into the sub-Antarctic wilds before Europeans arrived? Could Māori navigators, Fuegian mariners, or other Indigenous peoples have reached the last unpeopled latitudes of the planet?

A new study by Thomas Leppard of the University of Cambridge, John Cherry of Brown University, and Atholl Anderson of the Australian National University, published in The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology,1 takes this question apart with care and skepticism. Their answer is strikingly clear: no evidence supports the idea of Indigenous long-distance voyaging below 50°S before European contact. But, crucially, the authors argue this absence was not due to ignorance or inability. It was a matter of prudence.

“The lack of evidence does not reflect a lack of capacity,” says Dr. Leppard. “It reflects the rational limits of voyaging in environments that offered little reward and near-certain risk.”