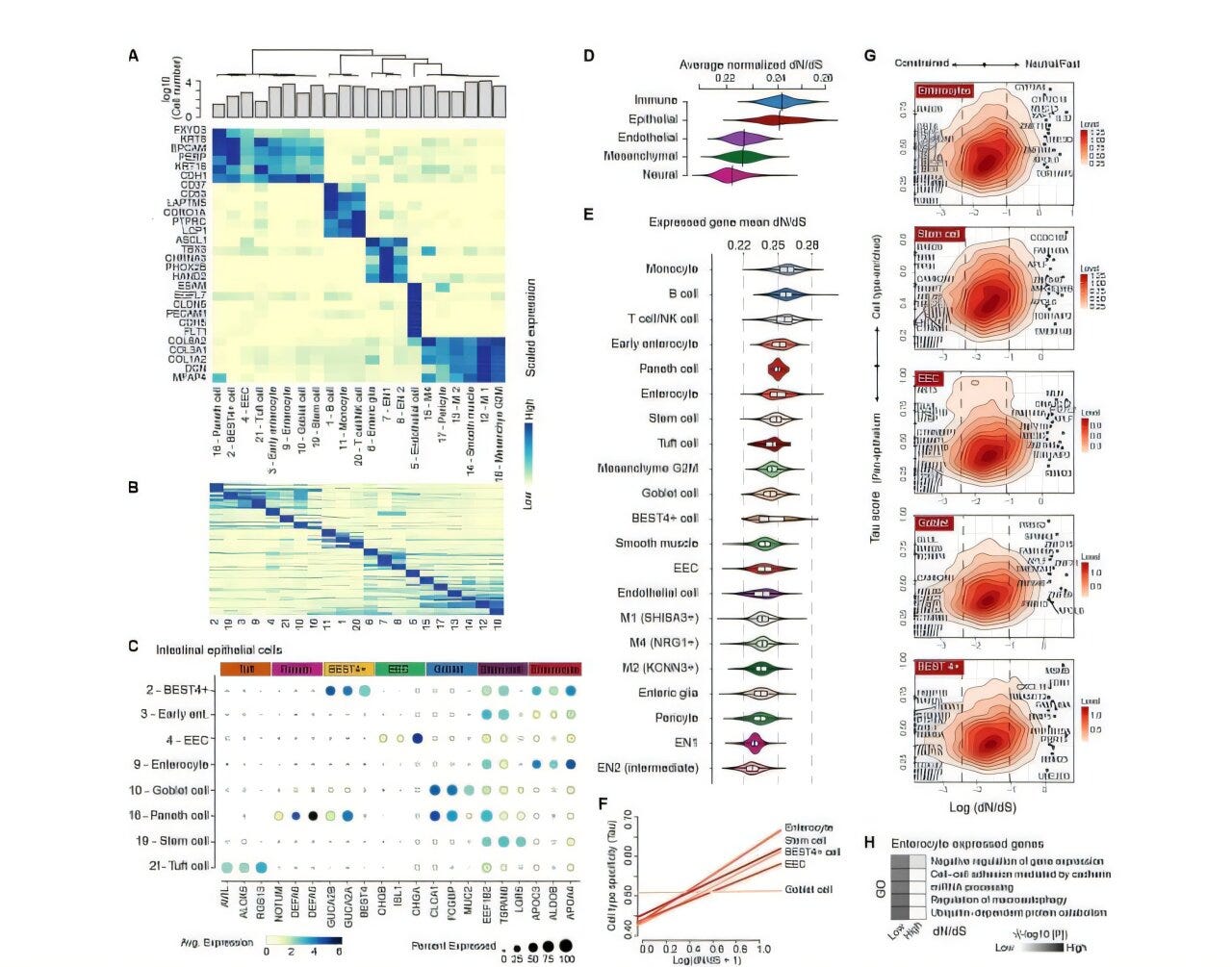

The small intestine doesn’t often take center stage in conversations about what makes humans unique. It lacks the drama of the brain and the charisma of bipedalism. But behind the scenes, this stretch of twisting tissue; long, soft, and unassuming, has been quietly evolving at a fast clip. According to a new study published in Science1, the modern human gut is not just different from that of mice or monkeys. It has transformed significantly even in comparison to our closest relatives, chimpanzees.

Led by a team of developmental biologists and evolutionary geneticists, the research reveals that the human intestinal epithelium; the cellular layer responsible for absorbing nutrients and defending against microbes has taken an evolutionary turn toward enhanced metabolic and barrier functions. This shift, the authors argue, has implications for everything from human dietary adaptation to susceptibility to digestive diseases.

“This study provides direct evidence that recent evolutionary changes in the human genome are shaping how the gut develops and functions,” said Gray Camp, one of the senior authors based at the Roche Innovation Center in Basel.