In the humid heart of the Yucatán, inside the ceremonial center of Chichén Itzá, a dozen ceramic bowls buried in history have begun to speak again. Through cracks, burn marks, and chemical traces, they offer a new clue to one of Mesoamerica’s most enduring aesthetic and ritual achievements: the production of Maya blue.

The pigment, renowned for its vibrancy and permanence, has captivated scientists since its rediscovery in the early 20th century. Found in murals, pottery, and on the bodies of sacrificial victims, this azure compound refused to fade, even after centuries in the tropical climate. But how it was made—how ancient artisans achieved this molecular resilience—remained unclear until the early 2000s, when chemical analysis linked the pigment’s creation to a trio of ingredients: indigo, palygorskite, and the sacred resin copal.

Now, more than 15 years after that breakthrough, new findings suggest the story is more complex. In a recent study presented at the Society for American Archaeology’s 2024 annual meeting and detailed in the newly published book Maya Blue (University Press of Colorado), anthropologist Dean Arnold proposes a second, previously undocumented method. This one, he argues, draws on a different sequence of preparation—one that hints at deeper ritual roles and restricted priestly knowledge.

Cracks in the Clay, Clues in the Fire

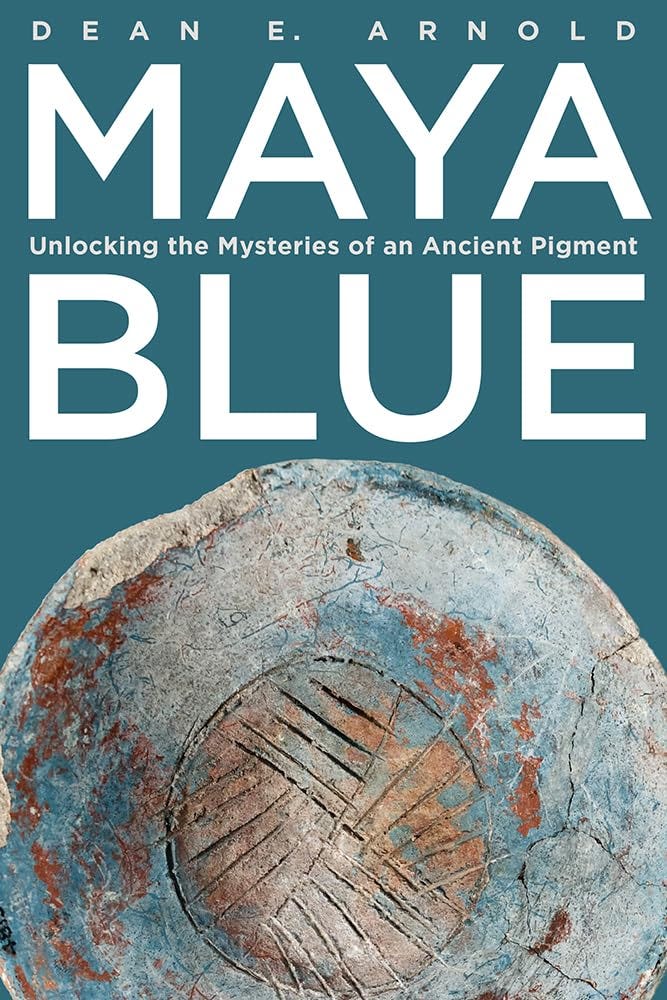

Arnold's investigation began not in a lab, but with close observation of ceramic artifacts: a dozen bowls excavated from Chichén Itzá, each bearing ghostly residues and signs of use. A white coating clung to the interiors, consistent with palygorskite, a fibrous magnesium-rich clay. But it wasn’t just the presence of the clay that intrigued him—it was how it had been processed.

Tiny fractures along the inside of the bowls pointed to wet grinding, a technique distinct from previous pigment-making reconstructions. In some bowls, microscopic plant remains were preserved—burnt stems trapped in place. The bases showed thermal scarring, suggesting that the bowls had been directly heated from below.

Together, these clues suggest an alternate recipe: plant matter (perhaps indigo-producing), palygorskite ground in water, then heated. Missing from this version is copal resin, once thought to be essential. In its place, Arnold hypothesizes, a different organic binder or sacrificial botanical element may have been used to coax the blue into being.

“The observations of these bowls provide evidence that the ancient Maya used this method as a second way to create Maya blue,” Arnold told colleagues during his presentation in Denver.

A Sacred Chemistry

Why develop two distinct methods to produce the same pigment? The answer may lie in the roles Maya blue played—not just as a pigment, but as a symbolic substance, tightly bound to cosmology and ceremony.

The color blue was more than visual—it was a spiritual medium. Maya blue was painted on sacrificial victims offered to Chaak, the storm and rain deity, particularly during periods of drought. In such contexts, the pigment was not mere decoration; it marked human bodies as transformed offerings, entangled with divine forces.

“This is a genius discovery that they made,” said Arnold, “and apparently the knowledge of it was limited to specialists like priests.”

The restricted access to this pigment’s production may have mirrored the broader stratification of Maya religious knowledge. Those who could produce Maya blue held not just technical skill, but ritual authority. The act of making the pigment—grinding, mixing, heating—may have been a form of invocation itself.

A Living Color, A Living Question

Despite the progress, the full story of Maya blue remains elusive. The genus of the plants used in the pigment’s creation has yet to be firmly identified. And the ritual logic behind the two separate methods—whether they were regionally specific, chronologically distinct, or purpose-driven—remains an open question.

What’s clear, however, is that Maya blue was never just a color. It was a material culture in miniature: sacred science, encoded in practice, surviving in pigment long after its makers were gone.

“The result of mixing indigo, palygorskite and copal,” Arnold once noted, “is also perhaps an incarnation of the rain god Chaak in this bowl after you heat it.”

In that light, each bowl becomes a kind of crucible—not just for pigment, but for belief.

Related Research

Arnold, D. E. (2024). Maya Blue. University Press of Colorado.

https://upcolorado.com/university-press-of-colorado/item/6507-maya-blueChiari, G., Giustetto, R., & Ricchiardi, G. (2003). "Crystal Structure Refinement of Palygorskite and Maya Blue from X-ray Powder Diffraction and Molecular Modeling." European Journal of Mineralogy, 15(1), 21–33.

DOI: 10.1127/0935-1221/2003/0015-0021Kleber, C., et al. (2008). "Deconstructing Maya Blue: A Recipe from the Past." European Journal of Mineralogy, 20(2), 341–348.

DOI: 10.1127/0935-1221/2008/0020-1820Magaloni Kerpel, D. (2014). Colors of the New World: Artists, Materials, and the Creation of the Florentine Codex. Getty Research Institute.