Picture a lakeshore in the Pliocene. The air is dry. Grasslands stretch across the horizon, interrupted by the charred skeletons of trees scorched by recent wildfire. Hominins cluster near the water, hands closing around stone cores and hammerstones. Flakes fly. A rhythm emerges. Chip, turn, strike, repeat.

That rhythm may have continued for hundreds of thousands of years.

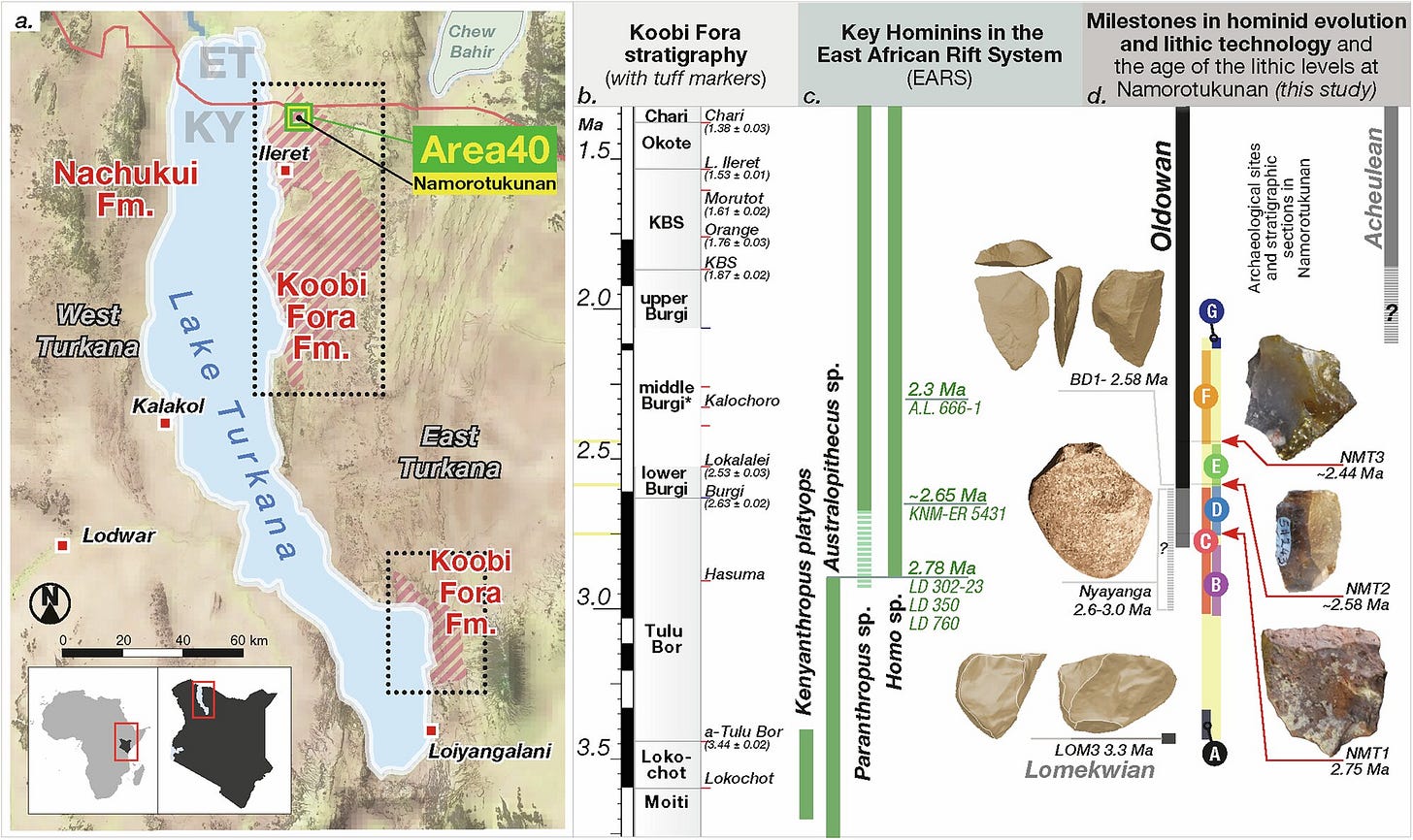

A newly published study in Nature Communications1 reports one of the longest and earliest records of Oldowan toolmaking yet discovered. On the western edge of Kenya’s Lake Turkana, at a site called Namorotukunan, archaeologists uncovered stone artifacts dating from roughly 2.75 to 2.44 million years ago. Across dramatic environmental upheaval, early hominins continued to make Oldowan tools with a consistency that borders on stubbornness.

For archaeologists, it sharpens an old question: When did technology stop being a momentary spark and become tradition?

This research, led by David Braun, Susana Carvalho, and colleagues, argues that long before Homo sapiens invented fire, boats, beads, or the bow, our ancestors had already mastered something even more fundamental: sticking with the tools that worked.