In the rolling hills of northern Spain’s Burgos province lies the Sierra de Atapuerca, an archaeological landscape famous for its deep record of human history. Among its many sites, El Mirador Cave has now yielded grim evidence1 of a violent episode that ended not only in death but in the consumption of human flesh.

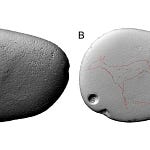

A team of archaeologists examined 5,056 human remains from the cave, belonging to at least 11 individuals. Microscopic analysis revealed a chilling pattern: slice marks from stone tools, scraping along bones, chop marks, burning, peeling, fresh fractures, and human tooth impressions. These were not the random scars of decay or burial. They told a story of people who had been skinned, disarticulated, cooked, and eaten.

Radiocarbon dates place the event between 5,700 and 5,570 years ago, within the Late Neolithic, a time when farming communities herded animals, cultivated crops, and competed for territory. Strontium isotope analysis indicated the victims were locals, suggesting the violence was not an attack by distant strangers but a conflict between neighboring groups.

“Cannibalism is one of the most complex behaviors to interpret, due to the inherent difficulty of understanding the act of humans consuming other humans,” explained Palmira Saladié of IPHES-CERCA and the Universitat Rovira i Virgili. “Societal biases tend to interpret it invariably as an act of barbarism.”

A Pattern of Violence in Neolithic Europe

Cannibalism at Atapuerca is not new. Earlier finds from the Gran Dolina cave, dating to the Early Bronze Age and even deeper into prehistory, also bear marks of butchery and consumption. Yet the El Mirador remains are distinctive. The proportion of modified bones is far higher than in funerary rites, where only a small fraction of bones are altered. The injuries are also distributed across the skeleton in ways consistent with butchering for meat, marrow, and brain.

Importantly, paleoenvironmental data did not indicate famine. The age range of the victims—spanning young to old—does not match the demographic profile expected in starvation events, which often claim the most vulnerable first. The authors argue that this was neither ritual cannibalism associated with burial nor survival cannibalism during hunger.

“The evidence points to a violent episode, given how quickly it all took place—possibly the result of conflict between neighboring farming communities,” said Francesc Marginedas of IPHES-CERCA and URV.

Consuming the Enemy

Ethnographic parallels reveal that in some small-scale societies, killing an enemy was not always the final act. Consuming the body could serve as the ultimate form of elimination—a denial of burial, a symbolic act of dominance, or a means of absorbing the enemy’s perceived strength.

Antonio Rodríguez-Hidalgo of the Institute of Archaeology–Mérida noted:

“Even in the less stratified and small-scale societies, violent episodes can occur in which the enemies could be consumed as a form of ultimate elimination.”

This find at El Mirador joins a growing catalogue of Neolithic massacres in Europe, from Talheim in Germany to San Juan ante Portam Latinam in Spain. Many involved not only killing but systematic treatment of bodies that speaks to deeply rooted cultural responses to conflict.

What Remains to Be Learned

The El Mirador bones capture a single violent event frozen in time. Yet questions remain. Were the victims targeted for political reasons, or was the violence rooted in resource competition? Was cannibalism an opportunistic act following slaughter, or was it a deliberate part of warfare? The archaeological record cannot yet answer these definitively. But the evidence is clear: for at least some Neolithic communities, the end of conflict was not the end of the enemy’s story.

Related Research

Fernández-Crespo, T., et al. (2020). Interpersonal violence at the dawn of the Neolithic in northwestern Mediterranean Europe. Scientific Reports, 10, 6450. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-63426-5

Boulestin, B., et al. (2009). Mass cannibalism in the Linear Pottery Culture at Herxheim (Palatinate, Germany). Antiquity, 83(321), 968–982. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003598X00099300

Alt, K. W., et al. (2020). A massacre of early Neolithic farmers in the high Pyrenees at Els Trocs, Spain. Scientific Reports, 10, 2136. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-59095-w

Saladié, P., et al. (2012). Intergroup cannibalism in the European Early Pleistocene: The range expansion and imbalance of power hypotheses. Journal of Human Evolution, 63(5), 682–695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2012.07.002

Saladié, P., Marginedas, F., Morales, J. I., Vergès, J. M., Allué, E., Expósito, I., Lozano, M., Martín, P., Iglesias-Bexiga, J., Fontanals, M., Marsal, R., Hernando, R., Burguet-Coca, A., & Rodríguez-Hidalgo, A. (2025). Evidence of neolithic cannibalism among farming communities at El Mirador cave, Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10266-w