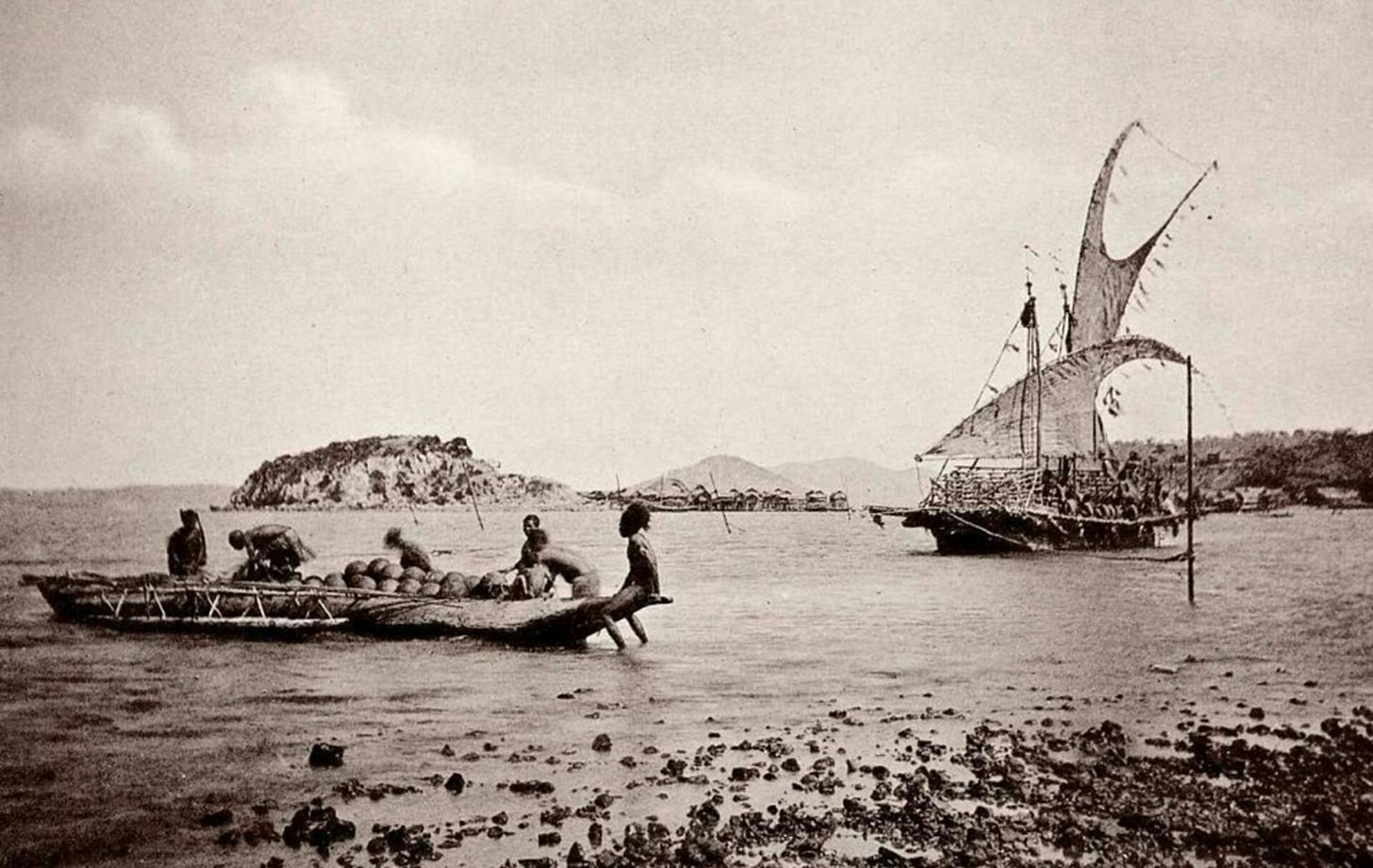

For decades, Papua New Guinea's rich maritime history was told through the lens of wind and war canoes. The story centered on the men—brave seafarers who launched long-distance expeditions along the south coast, carrying vast loads of pottery across hundreds of kilometers of ocean. The pots, the tales went, were forged by these navigators and traded for sago and food in far-off communities. But recent archaeological work has begun to reshape that narrative. A different force linked coastal societies—not only the wind in men’s sails, but the skill in women’s hands.

A study published in the Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory1 has uncovered new evidence of pottery production in Hood Bay, 100 kilometers east of Motupore Island. Using scanning electron microscopy to analyze the mineral signatures of clay and sand in pottery sherds, researchers discovered that what was long assumed to be traded ware from the west was, in fact, made locally. And the pots bore identical designs to those found at Motupore Island.

"This is the first direct evidence that earthenware pottery was made in Hood Bay," said Rebecca Skelly, the study's lead author. *"That craft tradition had disappeared sometime in the past few centuries, and its absence had long misled us about the nature of past exchange."

Parallel Pots, Shared Knowledge

The designs etched onto the Hood Bay pots are nearly indistinguishable from those of the Motu people of Port Moresby. Yet there was no evidence of direct seaborne trade linking the two sites. Instead, the study suggests something more subtle and human: a shared knowledge tradition, passed from woman to woman, across generations and geography.

"If the same pottery designs show up 100 kilometers apart, and men weren't involved in making them, then it points to a cultural transmission among women," said co-author Barbara Etschmann.

Indeed, historical accounts from the colonial era often overlook the role of women in crafting and knowledge-sharing. Much of what is known about Papua New Guinea's early trade comes from male anthropologists like Bronislaw Malinowski, whose famous 1922 work, Argonauts of the Western Pacific, likened the region's sailors to Homeric heroes. But the women, whose artistry fed those same trade networks, rarely made it into the pages.

When Pottery Carries Memory

Archaeologists excavating Hood Bay with the local Keapara community recovered pottery fragments strikingly similar to those at Motupore. But unlike past finds, these sherds revealed through microscopic analysis that they were made from local clay. This meant the similarities in design weren't the result of commodity exchange; they were the result of cultural exchange.

"The women who made these pots likely learned their craft not from traders but from other women—aunts, mothers, in-laws—possibly through marriage or prolonged contact," said co-author Tamara Beni.

The study also noted that the tattoo motifs worn by Motu and Keapara women in the 19th century were nearly identical. These tattoos marked major life transitions such as marriage and were deeply embedded in women’s cultural practices. Though the meaning of some of these shared patterns had already been forgotten by the time anthropologists began recording them, their distribution suggests sustained female interaction.

A Story of Interwoven Lives

The findings recast the role of women in shaping the south coast’s interconnectedness. While men navigated the sea, women wove together communities through knowledge. In the quiet acts of potting, tattooing, and mentoring, they maintained ties that extended beyond the horizon.

Pottery making is not a skill easily improvised. Among the Motu, women trained for years under the guidance of elder relatives, mastering clay selection, shaping, and decoration. The level of shared design seen across distant sites cannot be explained by coincidence or mimicry. It speaks to intentional learning, passed along routes invisible to the conventional trade maps: the movements of women.

"Pottery is more than a vessel," said co-author Fiona Petchey. *"It’s a container of memory, of skill, of relationship. And when we find its traces, we find the fingerprints of cultural continuity."

The Hidden Currents of History

This study offers a corrective to earlier models of cultural diffusion that emphasized objects over people, and male traders over female crafters. It proposes that, long before the colonial gaze settled on the daring exploits of seagoing men, generations of women were quietly sustaining and shaping cultural landscapes.

"We need to widen our view of what exchange means," said Jonathan Brugger, a mineralogist on the team. *"It’s not always about what moved across the water. Sometimes, it’s about what moved through memory."

As researchers continue work along the south coast of Papua New Guinea, attention is shifting toward the inland and the intimate—the places and relationships that stored cultural knowledge far from the gaze of early ethnographers.

The pottery, buried for centuries, tells a story that no trade manifest could capture: that the architects of tradition were not only the men who sailed, but the women who stayed—and shared.

Suggested Related Research:

Gosden, C. & Knowles, C. (2001). Collecting Colonialism: Material Culture and Colonial Change. Berg Publishers.

David, B., & Thomas, J. (2008). Landscape archaeology and the body: A review. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 18(2), 231–244. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774308000345

Kuechler, S. (2002). The Place of Cultural Exchange: Ritual and Agency in Pacific Pottery. Journal of Material Culture, 7(3), 299–314. https://doi.org/10.1177/135918350200700303

Torrence, R., & Summerhayes, G. R. (1997). Sociality and the short distance trader: Inference from obsidian artifacts in the Papua New Guinea highlands. World Archaeology, 29(3), 335–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.1997.9980394

Skelly, R., Etschmann, B., Brugger, J., Urwin, C., Petchey, F., & Beni, T. (2025). Uncovering hidden dynamics of past kinship and exchange relations on Papua New Guinea’s south coast (650–300 cal BP) through Scanning Electron Microscopy Automated Mineralogy analyses of pottery sherds. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 32(2). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-025-09710-y