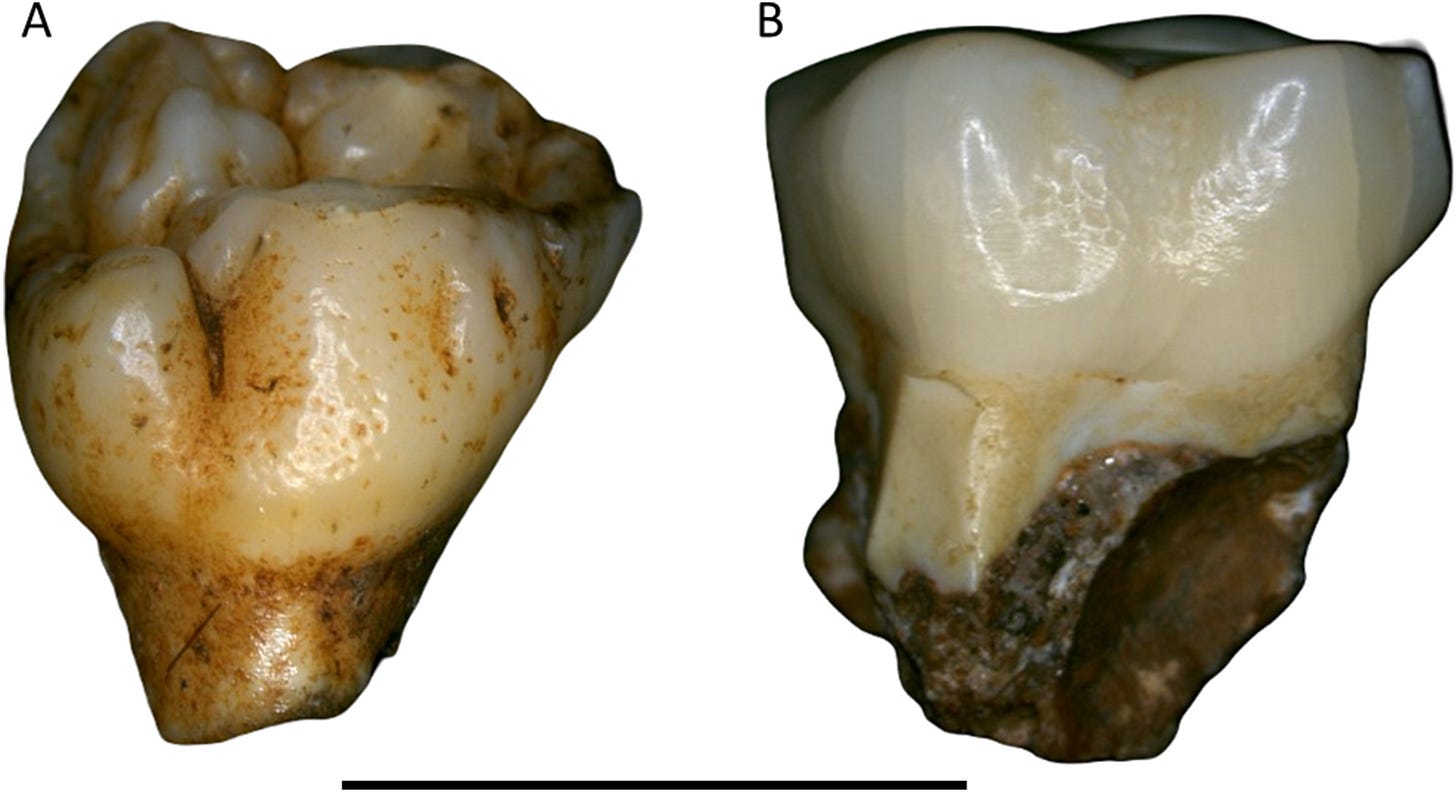

In paleoanthropology, the story is often written in bone. But sometimes, it's the fine details in enamel that rewrite what we think we know. A new study published in the Journal of Human Evolution1 dives deep—microscopically deep—into pitting enamel hypoplasia (PEH) to explore a peculiar and previously underappreciated dental trait called "uniform, circular, and shallow" (UCS) enamel pitting. Once thought to be confined to Paranthropus robustus, UCS pitting now appears in fossil teeth of other hominin taxa and might challenge assumptions about taxonomy and tooth development.

"The consistent appearance and distribution of UCS pitting across multiple Paranthropus and non-Paranthropus samples suggests a shared developmental origin, possibly genetic in nature," the study authors write.

What Exactly Is UCS Pitting?

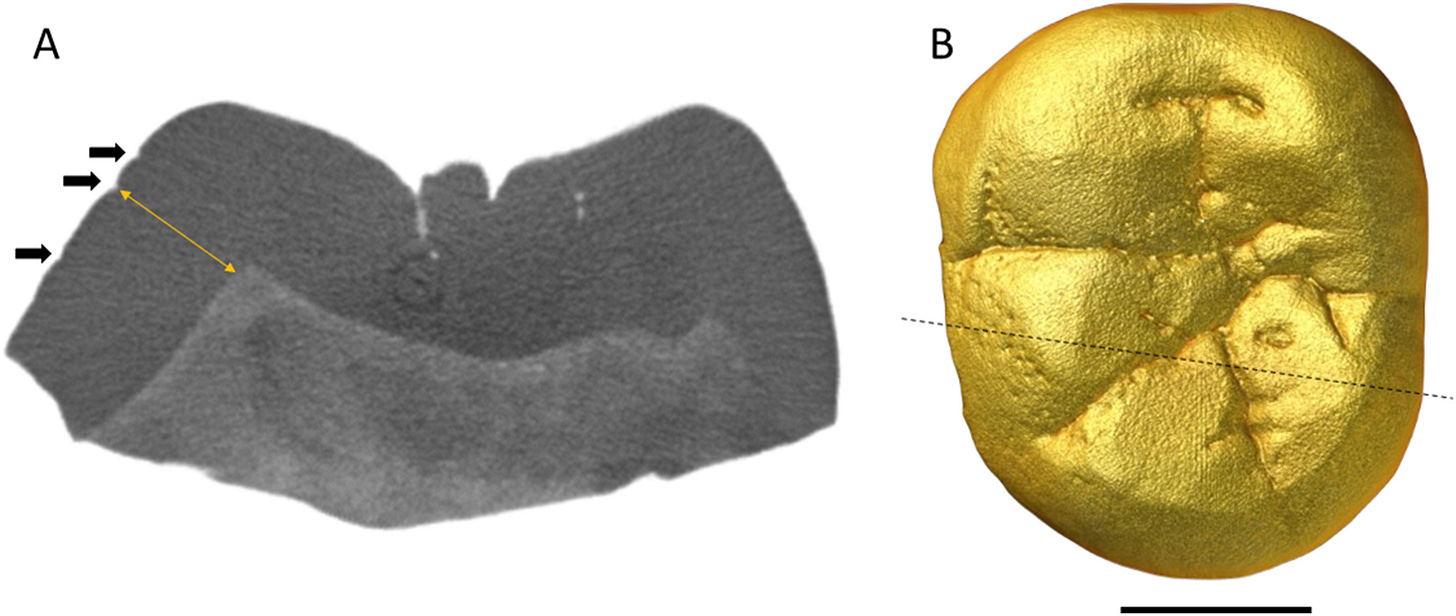

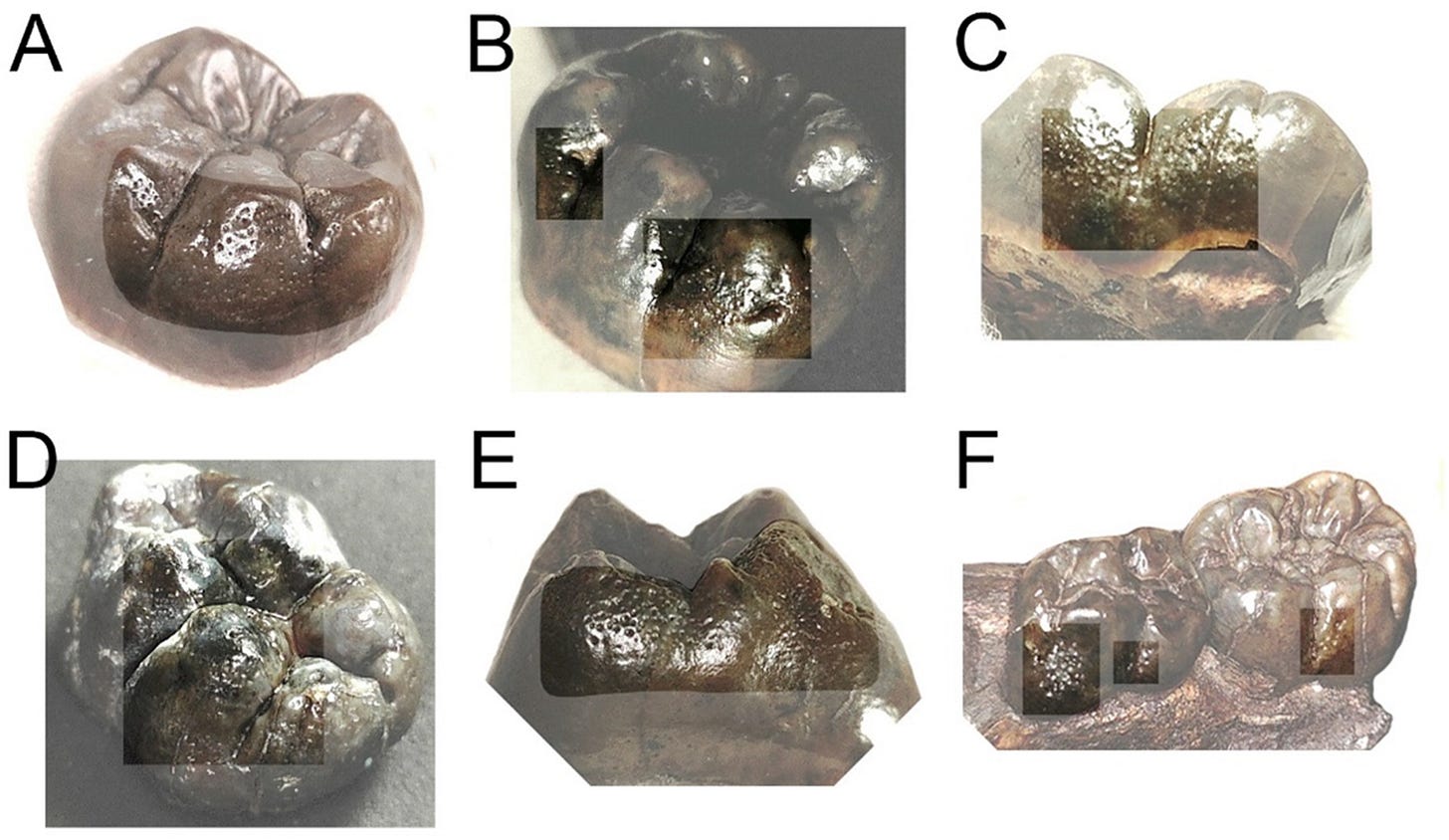

Enamel hypoplasia, broadly defined, refers to defects in the enamel layer of teeth that form during childhood development. These defects come in various types: linear bands, irregular patches, plane-form loss, and pitting. UCS pitting, as identified in this study, refers to shallow, circular pits—resembling a pattern of small dimples—that appear on the crown surfaces of teeth, often in a consistent, non-random distribution.

While PEH can result from systemic stress, illness, or nutritional deficiencies during enamel formation, the uniformity of UCS pitting led researchers to suspect a different cause—possibly a hereditary or developmental condition unrelated to short-term physiological stress.

From the Omo Valley to the Caves of South Africa

The study pulls together a large and diverse dataset of postcanine teeth—molars and premolars—from eastern and southern African sites. The eastern sample comes from the Omo Group deposits in Ethiopia, covering roughly 3.4 to 1.1 million years ago and including teeth attributed to Australopithecus, Paranthropus, and early Homo. The southern African sample includes specimens from Drimolen, Swartkrans, and Kromdraai—all associated with Paranthropus robustus.

In total, UCS pitting was documented in:

5 of 24 Paranthropus permanent teeth from the Omo sequence

5 of 13 permanent teeth attributed to Late Pliocene Australopithecus from Member B (~3 Ma)

Several teeth from southern African P. robustus samples, consistent with previous findings

"Despite spanning hundreds of thousands of years and multiple taxa, the morphology of UCS pitting remains strikingly similar across sites."

This consistency casts doubt on the idea that the pitting is purely a result of environmental stress. Instead, it hints at a deeper, possibly shared physiological or genetic trait—though the exact etiology remains elusive.

No Clear Links to Tooth Size or Enamel Thickness

One hypothesis tested in the study was whether UCS pitting is associated with megadontia—large teeth and thick enamel, traits common in Paranthropus. However, the data didn’t support this. Neither tooth size nor enamel thickness showed any consistent correlation with the presence of UCS pitting.

"Pit diameters and depths were remarkably consistent across individuals and tooth types, regardless of size or enamel metrics."

The researchers found UCS pitting on teeth with both high and low relative enamel thickness (RET) values, and in teeth of varying size and cusp morphology. This undermines the notion that UCS pitting is simply a byproduct of robust dental architecture.

Evolutionary and Taxonomic Implications

The presence of UCS pitting in both eastern African Paranthropus and Australopithecus specimens—along with a few ambiguous cases possibly linked to early Homo—challenges the assumption that this feature is taxonomically diagnostic for Paranthropus. If anything, it could indicate a broader developmental pattern among certain hominin lineages.

Moreover, the near absence of UCS pitting in Australopithecus africanus, Neanderthals, and modern humans underscores its unusual concentration in select fossil groups. A handful of similar cases have been noted outside Africa (e.g., Xujiayao in China), but these are rare and often tied to individuals with other cranial or dental anomalies.

"The appearance of UCS pitting in Late Pliocene Australopithecus may suggest that this condition either predates the emergence of Paranthropus, or reflects a convergent trait shared by geographically and temporally distinct populations."

A Tiny Window Into a Bigger Evolutionary Picture

Dental defects are often treated as epiphenomena—side notes in larger discussions about diet, health, and taxonomy. But this study shows that enamel can be a surprisingly stable archive, preserving subtle patterns of development and heritability that stretch back millions of years.

By rigorously documenting and defining UCS pitting, this work adds another layer to how paleoanthropologists interpret morphological variation. Whether this dental trait is a relic of deep evolutionary history or a more localized expression of enamel biology, it’s clear that tiny defects can carry big implications.

Related Research

Towle, I., & Irish, J. D. (2020). "A probable genetic origin for pitting enamel hypoplasia in Paranthropus robustus." Journal of Human Evolution, 146, 102863. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2020.102863

Skinner, M. F., & Newell, E. A. (2003). "Hominid dental development and enamel defects." International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, 13(6), 343-351. https://doi.org/10.1002/oa.700

Guatelli-Steinberg, D., et al. (2013). "Is pitting enamel hypoplasia an indicator of stress in fossil hominins?" American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 151(2), 277–286. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.22276

Skinner, M. M., et al. (2020). "Dental development and pathology in Australopithecus africanus from Sterkfontein, South Africa." PLOS ONE, 15(4), e0230991. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230991

Towle, I., O’Hara, M. C., Leece, A. B., Herries, A. I. R., Adjei, A., Guatelli-Steinberg, D., Martínez de Pinillos, M., Modesto-Mata, M., Thiebaut, A., Hernando, R., Irish, J. D., Guy, F., Boisserie, J.-R., & Hlusko, L. J. (2025). Uniform, circular, and shallow enamel pitting in hominins: Prevalence, morphological associations, and potential taxonomic significance. Journal of Human Evolution, 204(103703), 103703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2025.103703